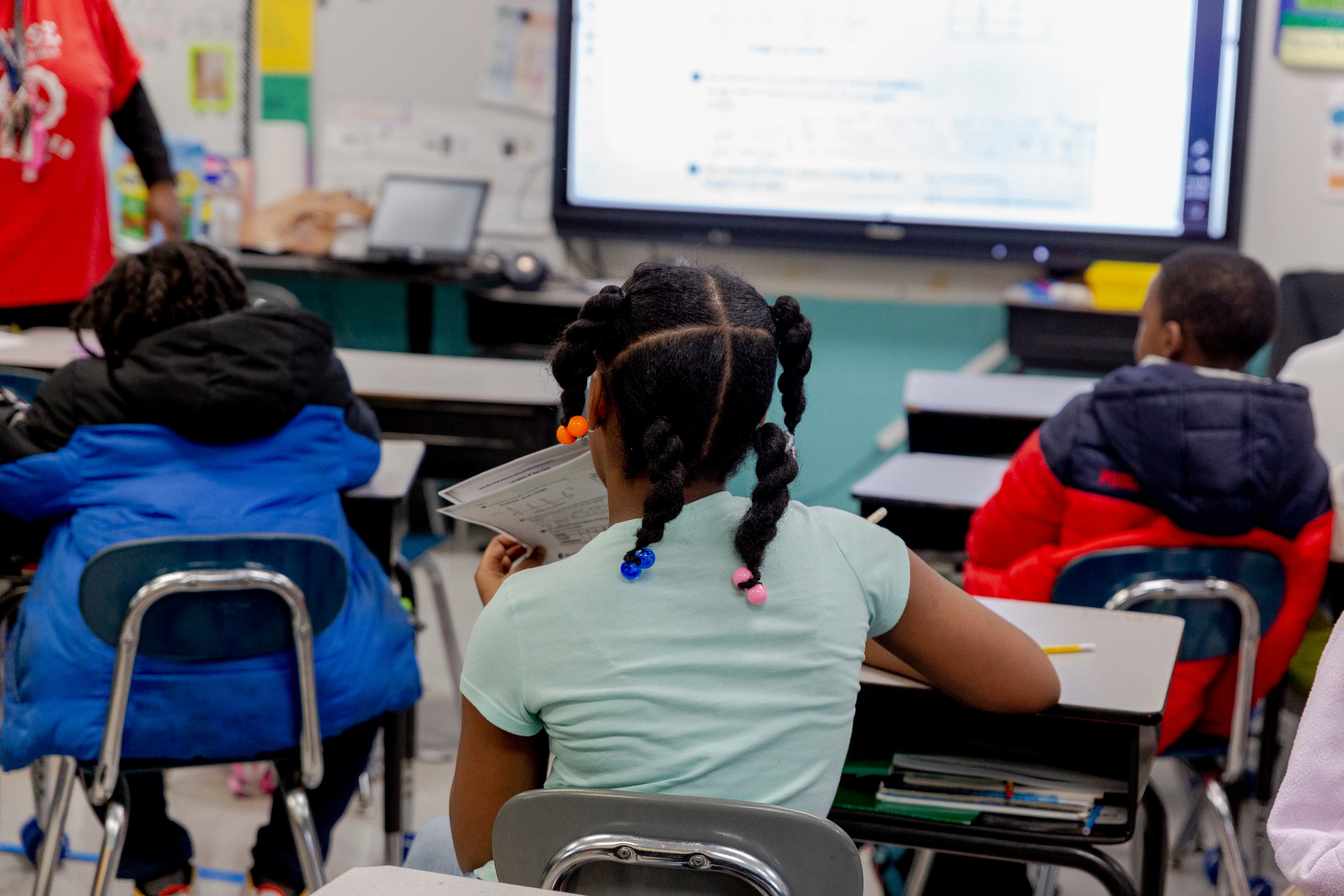

American students are slowly starting to regain academic ground lost during the pandemic, according to nationwide and state testing data compiled by Chalkbeat.

In the last year, students in younger grades have recovered between 15% and 35% of the learning they had lost, according to data released Tuesday by the testing group NWEA.

That’s the good news, particularly after a tumultuous school year that featured frequent staffing shortages, behavioral challenges, and student absences.

The bad news is that students — particularly low-income, Black, and Hispanic students — remain far behind where they would be if not for the pandemic. Recovery has been anemic or nonexistent in middle school, NWEA finds.

“At least the bleeding appears to have stopped, and we see some evidence that we’re closing those gaps ever so minimally,” said Karyn Lewis, an NWEA researcher. But at this pace, she said, it will take years for students to fully recover. “That timeline is pretty alarming.”

In addition to the latest NWEA results, Chalkbeat reviewed a host of academic data released by states and testing companies this spring and summer. Here’s what it all tells us about how American students are faring.

1. Schools and students have begun digging out of the learning loss hole — but they still have a long way to go.

In the first two years of pandemic-affected schooling, students made slower progress on math and reading tests than usual. The gap between where students are and where they likely would be if not for the pandemic is often referred to as “learning loss.”

Last spring, NWEA found that the average student had fallen 3 to 6 percentile points in reading and 8 to 12 points in math, depending on the grade. Now, NWEA is back with updated results, using data from over 8 million students.

In math, students in younger grades actually made slightly more progress last school year than in a typical pre-pandemic year. In reading, students made up ground last summer and then made normal progress during the school year.

Overall, younger students in the last year have made up roughly a quarter of their lost learning. For instance, students who were in second grade when the pandemic first hit in 2020 had fallen 10 percentile points behind in math by the spring of third grade. This spring, as they were completing fourth grade, the gap had shrunk to 7 points.

Results looked similar on a separate exam, the i-Ready, in preliminary findings shared with Chalkbeat. In second grade math, for example, 52% of students were on grade level at the end of last year, up from 49% the year before but far short of the pre-pandemic benchmark of 61%.

Another analysis from the company Amplify found that 48% of first graders in the middle of last school year were on track in early reading. That’s up from 44% from the year before, but still less than the 58% before the pandemic.

Recently released state test results from Florida, Indiana, Idaho, Tennessee, and Texas have also generally shown partial academic bouncebacks in 2022.

“We do see some good news here in terms of the upticks,” said Kristen Huff, vice president of assessment and research at Curriculum Associates, which produces the i-Ready. “But overall the students are still falling behind pre-pandemic performance.”

2. Older students may be recovering more slowly.

On the NWEA exams, students in seventh and eighth grade recovered almost none of the learning they lost. In fact, eighth graders fell further behind in math this year.

Results from other tests have varied, with some showing more progress for older students.

If older students have struggled to catch up, that’s especially concerning, since they have less time left in school.

“That should be the focus of the conversation: what are we going to do for kids in eighth grade or going into high school and they seem to be basically spinning their wheels?” said Vladimir Kogan, an education researcher at Ohio State University.

3. Gaps by race and poverty level are still worse than before the pandemic.

Gaps in test scores by student race and family income were already large before the pandemic. By 2021, they’d grown even larger.

The latest data from NWEA shows that in reading, high-poverty schools did make faster progress than low-poverty ones last school year, closing the gap ever so slightly. In math, though, progress was comparable in both types of schools, meaning the larger-than-usual gap hadn’t budged.

“We still see these really significant and staggering gaps overall,” said Lewis.

4. Learning loss recovery efforts may be paying off, though it’s impossible to say what exactly is working.

Schools across the country have been adding support to help students catch up. For instance, Woodland Hills, a high-poverty district outside Pittsburgh, has expanded summer and after school programming and bought a new online curriculum. Elementary schools have also added time for students to work in small groups on skills where they’re still beyond. Middle schools have doubled time for math classes.

“We’re seeing scholars starting to catch up,” said Eddie Wilson, assistant to the superintendent in the district. “It is very nascent.”

Still, students are far behind where they’d normally be. “We’ve got to move more quickly than we are right now,” Wilson said.

Many school districts still have COVID relief funds to use on learning loss recovery. That means there’s still time to add and expand that help, although the funding will dry up in a couple of years.

“Whether this creates a generation of kids who will never catch up or whether most of them do depends on what we do in the future,” said Paul Hill, who has reviewed evidence of learning loss for the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

One hurdle is that evidence of which recovery efforts have proven successful is limited. That makes it hard to figure which programs to expand and which to scrap.

“It was a really challenging year,” said Lewis. “That we see improvement at all, suggests to me that we are doing something right in helping kids catch up. I can’t say what that something is.”

5. There are likely lingering effects of remote schooling.

The latest research doesn’t distinguish between students who attended school virtually for a lengthy period and those who attended school in person since the fall of 2020. But prior studies, using data through spring of 2021, found that remote students fell further behind.

Because the gaps were so large and the academic comeback to date has been so modest, there’s a good chance that those students are still further behind.

Woodland Hills didn’t return for any in-person instruction until late March of 2021. Wilson says that although he supported this approach at the time, the district and its students are still grappling with its consequences.

“Now we know we do have to remediate 3,000 students because we chose to keep our students’ health as our priority,” he said. “If I had to go back and redo it, I would want to come back from virtual instruction a lot earlier than we did.”

6. These test scores probably do matter.

Research shows that test scores predict — not perfectly, but with some accuracy — whether students will finish high school, succeed in college, and earn a good living. At a national level, they predict economic growth. Studies of prior school disruptions have shown that test scores fall, and then high school and college completion falls, too.

That’s all to say that learning loss, if it persists, could end up being a serious problem both for individual students and the country as a whole.

7. The data we have is imperfect, though we’ll get better information soon.

The NWEA data only includes schools that opt in to take the exam, and those schools may not be perfectly representative of other places. Many states have not released their own test results, including large ones like California and New York, where many students were virtual for much of the 2020-21 school year.

But we’ll get better data soon. In the middle of last school year, the federal government administered exams to a national sample of fourth and eighth grade students. Those results are set to be released in the fall.

Matt Barnum is a national reporter covering education policy, politics, and research. Contact him at mbarnum@chalkbeat.org.