Mark Rogers went from teaching calculus to teaching kindergarten.

It was a big jump for the Texas teacher, but he did it because he believed in a practice called looping.

Looping is when students are taught by the same teacher for multiple years. Whether done intentionally or by chance, recent research shows this teaching technique can improve student academic performance and behavior.

Rogers came across looping by accident when an administrator at Meridian World School, a charter school north of Austin, Texas asked him to move up from eighth grade to fill an empty ninth grade algebra position. The first day teaching ninth grade was “completely different.”

“I knew everybody’s name. I knew everybody’s family situation. I knew how to differentiate for their needs,” he said. “There was a classroom community that had already had 12 months to develop. So I was blown away. This is so much easier. This is the way teaching is supposed to be.”

Rogers was such a fan of the teaching style that with each new year he volunteered to move up a grade with his students — even though it required learning new material. Eventually, he watched his high school seniors walk across the graduation stage.

“I saw how helpful it was taking kids from middle school, and then transitioning with them to high school,” Rogers said. “I thought to myself, well, what if we did that the whole way?”

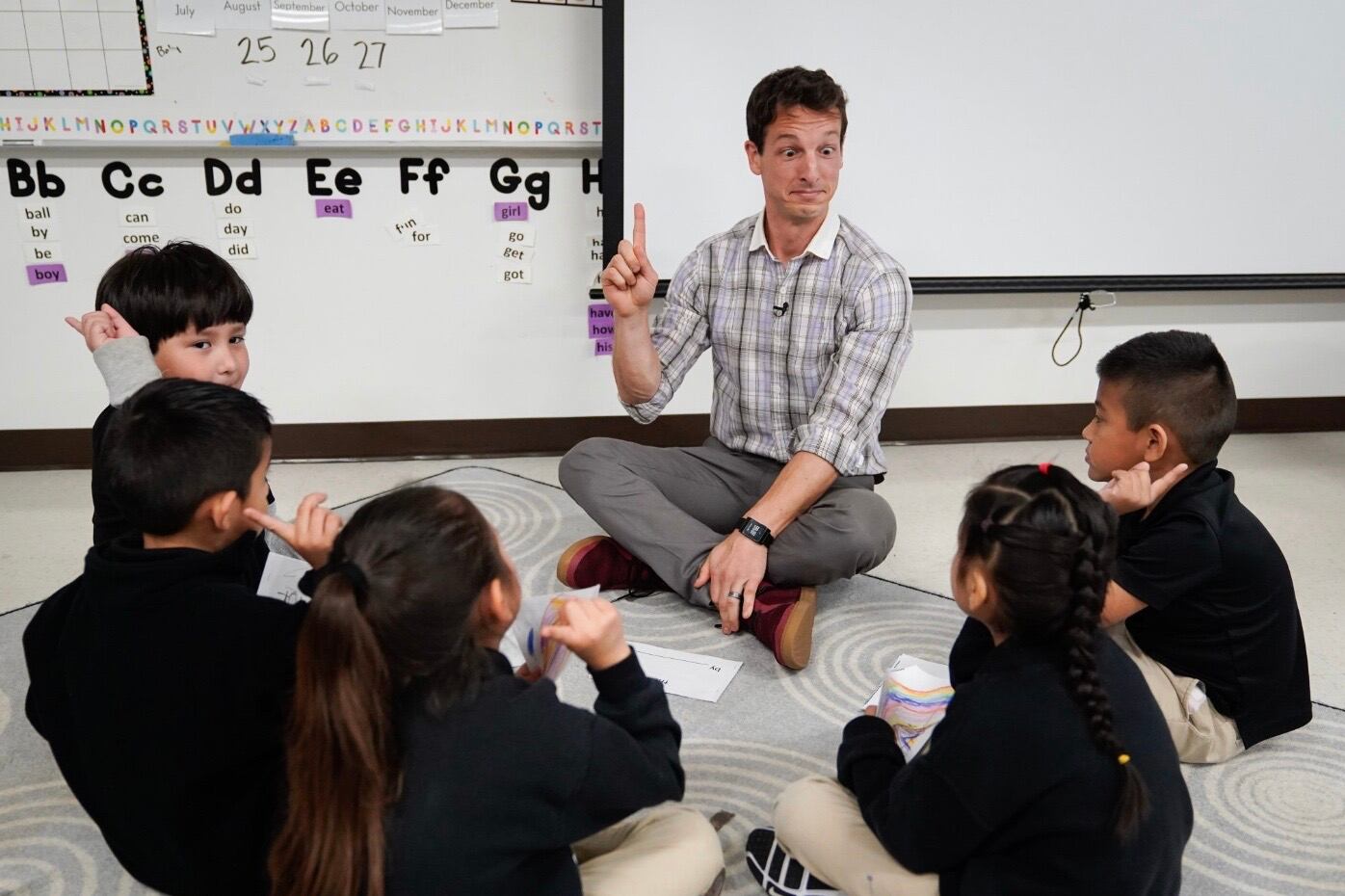

That thought spurred the move to kindergarten at a different charter school, Austin Achieve, which serves students from elementary through high school. Today, five years later, Rogers and his class are entering fourth grade, and he plans to stick with them until they walk across that graduation stage, too. (He was their lead classroom teacher from kindergarten through second grade and now teaches math and science to those same students.)

Chalkbeat spoke with Rogers about the benefits and challenges of his approach.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What are the most positive impacts of looping you’ve seen?

You can imagine that taking a calculus teacher and putting them into kindergarten, there’s going to be some bumps along the way. And I’ll be the first to admit that it was very challenging from a content perspective.

The amazing thing is that, even with those challenges, the kids who were with me in kindergarten had a class average of the 25th percentile when it came to national standardized testing data. In fact, I didn’t have a single student above the 40th percentile. And that’s normal, right? Kids come in and we’re going to teach them what they need to know. But what’s really cool is that even with a teacher like me, who is still grappling with the difference in curriculum and content and how to deliver it, because those kids have been in a really familiar environment, with their friends, and with me, and at the school, those kids have risen. So those same testing scores have increased. I’ve now got eight students who are in the 90th percentile or higher. And that’s just amazing growth to think about in four academic years, including a COVID disruption.

Any hurdles?

The pushback about learning new content. You can typically get around that and make teachers more comfortable with learning new content when they realize that we’re always learning something new. As a teacher, you’re either going to learn new content or you’re going to learn new kids. When I speak with teachers who are reticent to begin looping, that’s what really opens their eyes. Are we going to learn new content and loop with our kids? Or are we going to learn completely new kids, and stick with the same content? When we start to think about how challenging it was to learn the unique characteristics and traits of a child, and how you can build trust with them, I mean, that’s the special sauce of education.

The hurdle with the teachers, that’s easy to overcome. The harder one I’ve found is that if it’s not a school priority from leadership, then looping has a really tough time getting started. So if a principal isn’t bought into the data-driven benefits of looping, it’s very hard. That’s part of the work that I do now is meeting with administrators and helping them see through not only anecdotal evidence from me and other looping teachers, but also nationally, what looping does in very large data sets to improve attendance, academics, and behavior.

Tell me about a memory with your class over the last five years.

For anonymity purposes, we’ll call this kid James. James was with us kindergarten through second grade, but [Austin Achieve] was a little further away than the other school he would have been zoned for. So James actually left our class for the third grade year [2021-22]. And James missed us so much that James convinced his mother to bring him whenever he had a school holiday that didn’t overlap with our calendar. He’d just come to school and sit in our class. That happened three times. I mean, think about that, a kid voluntarily going to extra school to be with his friends.

James was just sad. He missed his teacher. He missed his friends. He missed our environment that we had spent three years building together. And I’m really happy and almost going to tear up. James’s mother called me two weeks ago and was like, we want to come back. He finally set foot in the class, and the smiles on James’s face tell me everything I’ll ever need to know about looping.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your classroom or your school?

The primary community issue that we see right now is housing price inflation. Ninety-five percent of our kids are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. And so housing price inflation has been so challenging in a lot of places, especially in Austin, Texas, where the median sales price for a house has doubled in the last 10 years and rent along with it.

One student’s family came to me in tears. They’re like, ‘I’m sorry, we have to move to Bastrop, a smaller city southeast of Austin. We’ll pay half in rent. We can’t afford to live here anymore.’ And so she moved to Bastrop Independent School District. A special looped class like this one is one thing. But just to lose the ability to go to your own school because you can’t afford to live in the city anymore, that was really challenging.

As you prepare for the coming school year, what are you most looking forward to?

I believe that kids all learn at different rates and at different times. I think every kid in my class is a genius, and they have genius in different areas. My goal is to continue to grow and cultivate the genius in the children that I haven’t had a chance to do that with. And the coolest part about looping is you do get another chance.

Jessica Blake is a summer reporting intern for the Chalkbeat national desk. Contact her at jblake@chalkbeat.org or on Twitter at @JessicaEBlake.