This story was co-published with USA Today.

Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

When it comes to how American students are recovering from the pandemic, it’s a tale of two subjects.

States across the country have made some progress in math over the last two years, while in English language arts some states made gains while others fell further behind.

“In math, almost every state looks pretty similar. There was a large decline between 2019 and 2021. And then everybody is kind of crawling it back,” said Emily Oster, a Brown University economist. “In ELA, it’s all over the map.”

That’s according to recently released results from over 20 state tests, encompassing millions of students, compiled by Oster and colleagues. The scores offer among the most comprehensive national pictures of student learning, pointing to some progress but persistent challenges. With just a handful of exceptions, students in 2023 are less likely to be proficient than in 2019, the year before the pandemic jolted American schools and society.

“Schools are getting back to normal, but kids still have a ways to go,” said Scott Marion, executive director of the Center for Assessment, a nonprofit that works with states to develop tests. “We’re not getting out of this in two years.”

Oster’s analysis of test data tracks the share of students who were proficient on grades 3-8 math and reading exams before, during, and after the pandemic. Every state showed a significant drop in proficiency between 2019 and 2021, a fact that has been documented on a variety of tests. (Testing was canceled in 2020.)

Prior studies from Oster and others have found that while schools of all stripes saw test scores decline during the pandemic, those that remained virtual for longer experienced deeper setbacks.

The recent state test data offers some good news, though: 2021 was, for the most part, the bottom of the learning loss hole.

In math, all but a couple states experienced improvements between 2021 and 2023. Only two — Iowa and Mississippi — were at or above 2019 levels, though.

In reading, a majority of states have made some progress since 2021 and four have caught up to pre-pandemic levels. However, numerous states experienced no improvement. A handful even continued to regress.

It’s not clear why state trends in math versus reading have differed. After the pandemic hit and closed down schools, math scores fell more quickly and sharply than reading, but now appear to have been faster to recover.

Testing experts say that standardized tests may be better at measuring the discrete skills that students are taught in math. Reading — especially the comprehension of texts — comes through the development of more cumulative knowledge and skills. “Is the test insensitive to what’s really going on in classrooms or are kids just not learning to read better?” said Marion. “That’s the part I can’t quite figure out.”

Oster suspects the adoption of research-aligned reading practices, including phonics, may explain why some states have made a quicker comeback. Mississippi, well known for its early adoption of these practices, is one of four states to have fully recovered in ELA. But more research is needed to understand why some states appear to have bounced back more quickly than others.

“Some people are doing a good job. Some people are not doing as good a job,” said Oster. “Understanding that would tell us something about which kind of policies we might want to favor.”

Some schools look to phonics to boost stagnant reading scores.

In Indiana, which made gains in math but not reading, officials are hoping a suite of recent laws embracing the science of reading will boost scores. In Michigan, which also saw no progress in reading, lawmakers pointed to recent investments in early literacy efforts and tutoring.

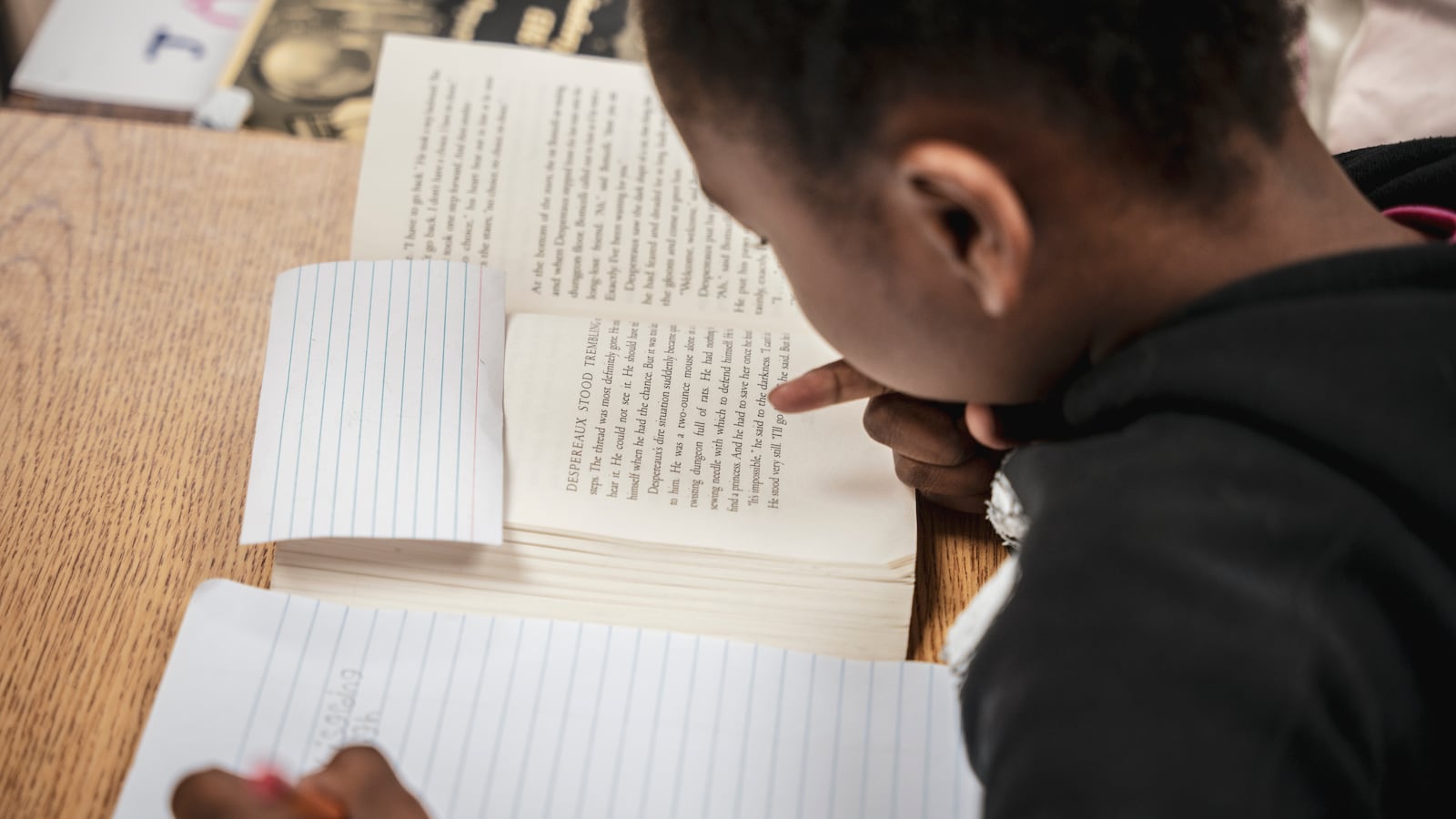

At Sherlock Elementary, part of the Cicero 99 school district in Illinois, just west of Chicago, Principal Joanna Lago saw how the pandemic set students back. Students are still climbing out of those holes, she said.

“Our scores are somewhat stagnant,” she said.

But Lago is hopeful a series of new initiatives will lead to gains for her students. This year, her district is adding an extra 30 minutes to every school day so staff can zero in on reading and math skills. This is the second year that teachers within the same grade level are working together more closely to plan lessons and review student performance data.

The district has also adopted a new reading curriculum aligned with the science of reading. Over the last two years, Lago, a former reading teacher herself, and her team got training on using decodable texts to emphasize phonics. Teachers visited each other’s classrooms to observe as they tried out new lessons. Pictures of mouths forming letter sounds now hang on classroom walls, instead of pictures of words.

It’s “a more strategic approach to help reach kids and fill some of the gaps of what they need,” Lago said. “How could this not lead to results? How could this not lead to more kids reading more fluently, having better reading comprehension?”

Educators are confronting persistent learning loss going into the last full school year to spend federal COVID relief money, a chunk of which is earmarked for learning recovery. Some school districts have already begun to wind down tutoring and other support as the money dwindles.

Marion of the Center for Assessment fears this extra programming will vanish too soon. “I’m pessimistic because I’m pessimistic about politicians,” he said.

The state test scores offer a slightly different picture of learning loss than a recent analysis by the testing company NWEA. While NWEA found little evidence of recovery last school year, most state tests showed gains in math proficiency last year.

There could be a number of reasons for this discrepancy, including the fact that some large states — including California and New York — have not released state test data yet, so the picture is still incomplete.

The new test score data comes with a few other caveats. Because states administer their own exams and create different benchmarks for proficiency, results from different states are not directly comparable to each other. Experts also warn that proficiency is an imprecise gauge of learning since it captures only whether a student meets a certain threshold, without considering how far above or below they are.

Plus, each year’s scores are based on different groups of students since regular testing ends in eighth grade. That means students fall out of the data as they progress into high school and some may never have fully recovered academically, even if state average scores have returned to pre-pandemic levels.

“There are kids who will forever be behind,” said Oster.

Matt Barnum is interim national editor, overseeing and contributing to Chalkbeat’s coverage of national education issues. Contact him at mbarnum@chalkbeat.org.

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.