Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

Former Education Secretary Arne Duncan wants the country to adopt a unifying set of ambitious education goals, but he doubts any politician will lead the way in doing so.

“I would love us to try to agree on some goals,” he said Tuesday afternoon, before noting later, “I don’t have a lot of optimism that it’s going to come at the national level.”

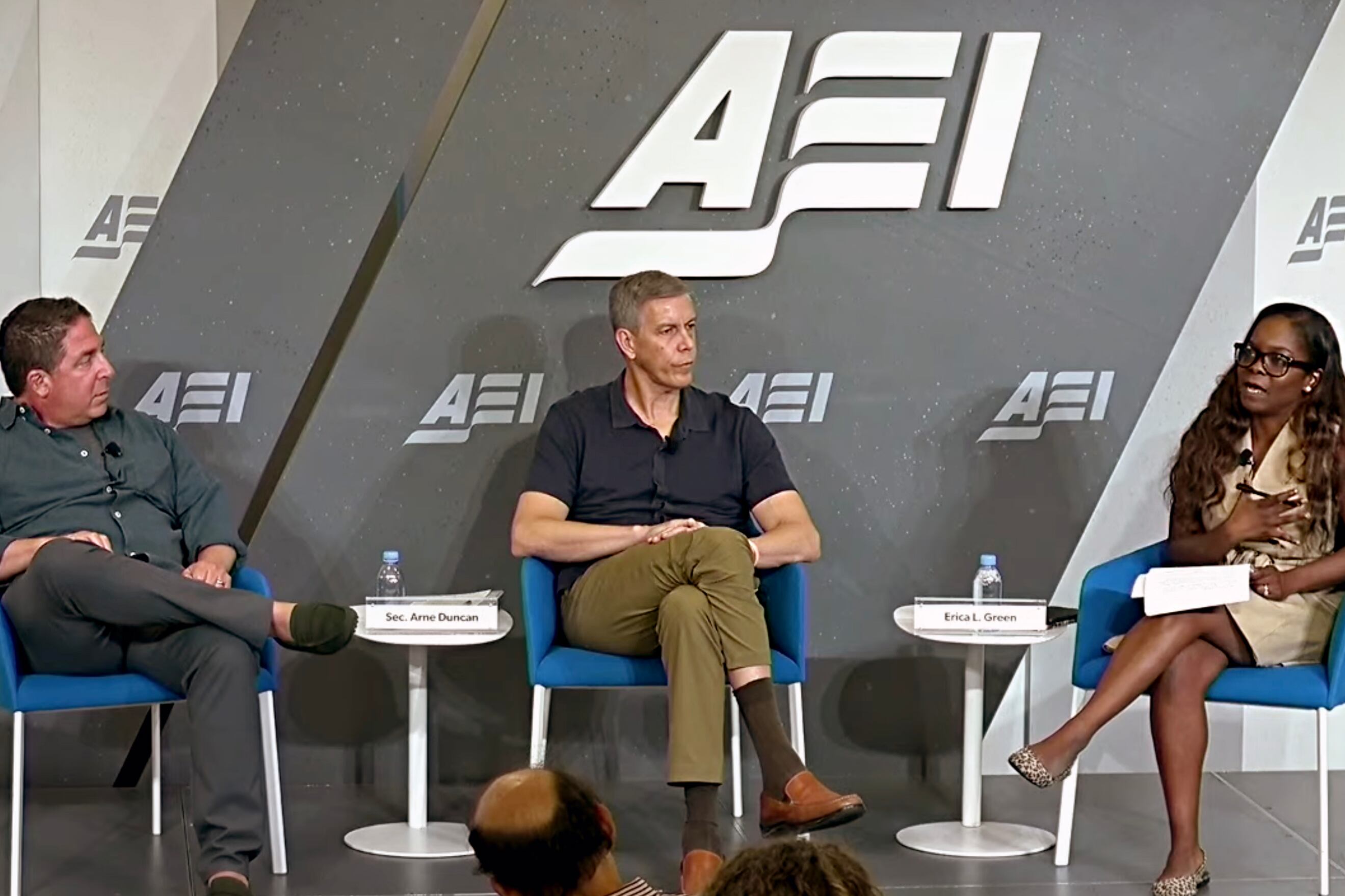

Duncan, who was a member of the Obama administration, spoke at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank at an event titled, “A Way Forward for School Reform.” But Duncan and Frederick Hess, AEI’s director of education policy, suggested that there is no clear way forward.

In the background of this discussion was recent history: A particular brand of bipartisan education reform — which emphasized charter schools and accountability for student test scores — dominated Washington during the Clinton, Bush, and Obama administrations. Now it’s in the rearview mirror, and there’s no indication it’s coming back.

The forum highlighted how the parties are further apart on education than at any point in recent memory. And the discussion pointed to why no bipartisan collaboration on education appears to be in the offing, despite nascent efforts to create one and unprecedented challenges faced by the country’s schools. In short, the politics have changed and there’s no education agenda that is unifying both parties.

“How do you think about solutions that are going to feel relevant and are capable of building broad support in a different political landscape?” said Hess. “Anybody who says we do that by going back to the playbook that resonated between 1992 and 2012 is, I think, probably misleading themselves.”

The forum was the latest rumbling about the idea of reviving what had been a dominant strain of education policy.

Last month, a small cadre of nonprofit leaders published a manifesto titled “A Generation at Risk: A Call to Action.” (This is a reference to “A Nation at Risk,” the 1983 federal government report that spurred a national bipartisan focus on improving schools.)

The report was the result of covenings of “a group of education advocates from the Left, Right, and Center,” as part of a “building bridges initiative” organized by Democrats for Education Reform and the Fordham Institute, a right-of-center education think tank.

“We all agree that we need a bold vision for change, leadership that works across lines of difference, and decisive action if we are to make good on America’s promises to our children, today and in the future,” the report says.

Duncan, who now runs an organization that seeks to reduce gun violence in Chicago, said he wants agreed-upon national goals focusing on access to prekindergarten, third grade reading, high school graduation, and college completion. He also suggested that he would like to see a renewed cross-party effort to improve schools. “I really miss trying to work in a bipartisan way,” said Duncan.

That seems a bit quixotic at the moment.

Former President Donald Trump appears likely to be the Republican nominee. His campaign has emphasized culture-war issues in education and Trump has said he would try to abolish the U.S. Department of Education.

President Joe Biden has been quiet on K-12 education policy. Policy-wise, his administration has focused on increasing spending for schools, while Congressional Republicans have sought to cut education budgets.

Duncan suggested that a new focus on improving education might come from families, but acknowledged that most parents like their own child’s school — a fact that has persisted even in the wake of the pandemic.

Another challenge for reassembling the old coalition is that it’s not clear what their policy agenda would be. The Generation at Risk report promotes high-level ideas like “set goals aligned to recovery,” “rethink how time and staff are used,” and “evaluate emerging innovations.” It’s not clear how these would be translated into federal policy that would affect schools, though. At the AEI event there was only limited discussion of specific ideas for improving schools.

This contrasts with the heyday of bipartisan school reform when advocates were aligned on a number of concrete policies, like the Common Core standards, increasing the number of charter schools, and test-based accountability for teachers and schools.

Those policies have a mixed — and still-debated — legacy. Research found that No Child Left Behind contributed to improvements in math test scores and graduation rates. But studies on Common Core and teacher evaluations showed little if any benefits. Recent research on charter schools have leaned more positive.

At the moment, though, education policy has been dominated by debates over what gets taught in school, particularly around race and gender. Hess noted that as a historical matter that’s hardly unusual.

“Most of our history has been fighting over what books do you read and about how do you teach our history,” he said. “However we want to define school reform, maybe that’s not how the families and the people who schools are serving are actually thinking about the work of school reform.”

Matt Barnum is interim national editor, overseeing and contributing to Chalkbeat’s coverage of national education issues. Contact him at mbarnum@chalkbeat.org.