Casey Stockstill didn’t set out to write a book about preschool segregation.

Initially, the Dartmouth College sociologist wanted to write about the lives of preschoolers. To do that, Stockstill spent two years observing children and staff at a Head Start in Madison, Wisconsin, followed by spending a month at a private preschool on the other side of the city.

Sunshine Head Start enrolled nearly all kids of color, while Great Beginnings was nearly all white. But both were top-rated preschools with experienced staff, a teacher for every six students, and a routine filled with learning and play. So Stockstill expected they’d be pretty similar.

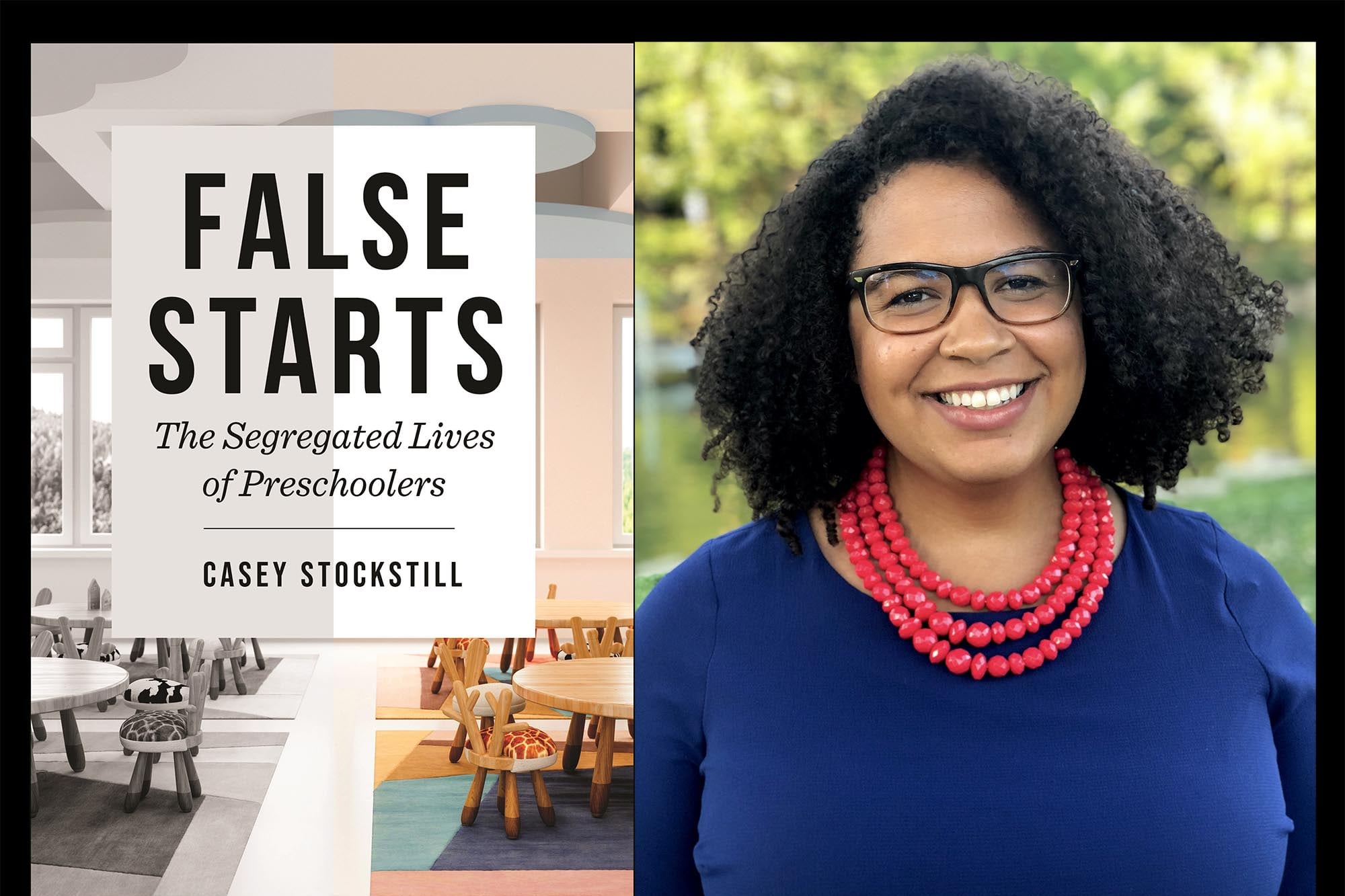

But the stark differences she observed — all of which were rooted in racial and socioeconomic segregation — became the organizing principle of her new book, “False Starts: The Segregated Lives of Preschoolers.” In it, Stockstill details how segregation shapes everything from how preschoolers spend their time to the kind of instruction and supervision they receive.

That matters because preschool segregation is not only common, but often overlooked. Nationally, two-thirds of preschoolers learn alongside classmates who are either mostly white and affluent, or mostly kids of color from low-income families. And early childhood programs are more racially segregated than K-12 schools.

Chalkbeat spoke with Stockstill about those differences she saw, and how they affect the kind and quality of education preschoolers receive.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

On paper, these two high-quality preKs have a lot of similarities. Can you talk about how students spent their time when you were there?

The first thing I noticed was: Wow, their listed routine looks so similar. It says they’re going to come in and say welcome, have breakfast, have circle time on the rug, an hour of open-ended play, go outside, and eat lunch.

Watching them on a daily basis though [was very different]. At Great Beginnings, things are pretty calm and predictable. I went in February to observe, all the kids had been enrolled since September. It was like: We know who is coming every day, and these kids know the routine.

What surprised me was how much the kids read books. One time, I watched the teachers read a book to a group of 4-year-olds for 32 minutes with no major interruptions.

At Head Start, they always tried to read every day, but they often didn’t finish the book. They either had kids that had been enrolled in their class all year, but were having a hard day, because stuff was going on at home. So those kids are running away from the circle, or poking a friend, and they’re having to stop and correct those behaviors.

Or they have this churn in part of their enrollment. Two-thirds of the Head Start class roster was stable. The kids were there in September, they stayed all year. One-third just rotated based on poverty and instability. We had a student, her family got evicted, that left a spot open for a new family to come in. So you’re kind of constantly in orientation mode.

How did segregation affect what was going on in their classrooms?

We have a country that has structural racism, and a country that has pretty harsh conditions of poverty, especially for children. Families of color have higher rates of experiencing things like eviction, having a parent that gets incarcerated, contact with Child Protective Services and foster care. All of those things are more likely to happen to Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous children. Families who are poor, similarly, have higher rates of residential instability.

If we had integrated classrooms, where 20% of preschoolers were poor in every single center, we would spread out those challenges, and we’d force all teachers to think about how they’re going to meet kids’ needs when they have some kids dealing with these instabilities and disruptions to family life. Instead, when we segregate kids, you make a classroom like Sunshine Head Start, where we have a lot of those problems. That allows you to have other classrooms like Great Beginnings, where none of those problems exist.

Can you talk about how the segregated classroom experiences affected whether or not kids could bring things from home?

Sunshine Head Start had a classroom rule that you could not bring personal toys from home. There was no stuffed animal you would bring to nap. This rule made sense to the teachers, because they knew they had kids who were homeless, they had kids getting evicted. They didn’t want to create more moments to underline that kind of scarcity. And the other thing they said was: We have this classroom full of toys.

In that environment, about a third of the kids that I observed tried to sneak in special objects to school. It was mostly boys of color that would bring in a Spider-Man toy, a bouncy ball, a slimy, sticky hand. Boys were likely to get caught with these objects and then they would get disciplined for it. They’d get: ‘You’re not supposed to do that, put it in this bin, I’m going to take it away.’ It became this source of friction and distance between the kids and the teachers.

What I argue in the book is that this sends a message to the whole group of children that you check your personal stuff at the door. School is for playing with the institutional objects that we’re providing for you. For this one-third of kids who snuck things in, and then got in trouble, I see that it can feed into disproportionate discipline. We have statistics on this, that Black preschoolers are suspended and expelled at higher rates than white preschoolers. At Sunshine Head Start, none of the kids got suspended, but they did experience this avenue of discipline.

Then I went to Great Beginnings. They didn’t sneak things in, and it was because they had a weekly show-and-tell with the letter of the week. It might be ‘O’ and you’d bring in your baby owl stuffed animal. They also could bring in a stuffed animal at nap time, and they would play with those things.

At Head Start, they’re dealing with real scarcity among their families. They’re trying to make that not an issue, and so they have this strict policy, but it doesn’t really work. And at Great Beginnings they’re basically celebrating material abundance.

When you saw the kids get their things taken away who’d snuck them in, how did that affect them?

It depended. I focus a lot on a child I call Julian, who was dealing with a lot of family instability. His mom was incarcerated, she was in jail for a month. He just had a lot going on at home. And he would bring in stuff a lot. Sometimes, he was able to hide it from the teachers. Toward the middle of the year, it started getting taken away more often, and he would be upset about that.

But what was interesting was that by the end of the year, he had kind of learned how to bring stuff in and make sure the teachers didn’t see it. He would make plans. That also concerns me. There are kids who are learning not only that the teachers can’t know I’m bringing special things to school, because I’ll get punished, but also now I’m able to practice maneuvering away from the teacher’s gaze.

Another thing you detail in the book are the differences in play time, and who sets the rules for how kids play. Could you talk about that?

You might expect marginalized children, poor children of color, would get less autonomy. It’s kind of the opposite of what I observed.

At Sunshine Head Start, again, those issues of the fluctuating enrollment, the behavior challenges from kids, dealing with family instability — those things occupied teachers’ attention during the indoor playtime. They’re doing this hour of what’s supposed to be open-ended play. And the teachers would pair up with the kids who were acting out, or new to the classroom. Sunshine Head Start had three teachers, two of them were often paired up with kids in this unofficial way, leaving one teacher to supervise the other 15 kids.

So you’d have these pockets of three to seven children, who are playing, and they are being supervised, but the teacher is not involved in what they are doing. They are figuring that out themselves. The classroom rules also gave kids a lot of autonomy. In circle time, they’d say where do you want to play? What’s your plan?

The result of that was that the Sunshine Head Start kids were used to playing and a random classmate wanting to join the game. They would have a lot of problems, and then they would have to solve them themselves.

Then I went to Great Beginnings, where they had what they would call an hour of open-ended playtime. But they exerted more control. They assigned kids to play centers. They’d set a timer for about 15 minutes, and when the timer beeped, you would rotate to a new play area with the same playmate. They don’t deal with this issue of: What if you’re playing a game and two new kids want to join? The teachers were highly involved.

I see downsides to that: Less creativity, less independent problem-solving. But the potential upside is: Now you have kids who are expecting adult attention. There is a lot of sociology work on this in elementary school, about middle-class kids interrupting, raising their hand, just exhibiting more entitlement to teacher attention.

The students who had higher concentrations of poverty in their classrooms experienced higher levels of intrusion into their families’ lives. What was most striking to you about that dynamic?

Because of the experiences that poor families are having outside the classroom of surveillance and fear of Child Protective Services calls — those enter into the classroom with teachers feeling hesitant to ask questions. They told me they feared they would get in trouble if they seemed like they were prying for information about family challenges.

What was interesting to me is: The kids would talk about some of their family events but the teachers didn’t see that as bids to have a bigger conversation. They didn’t feel they could talk openly about a domestic violence dispute or scarcity at home. Kids have to kind of learn that these things happening at home are not acceptable talking points at school.

And at Great Beginnings, those families have disruptions as well, but the ones I saw were kind of upper-middle-class disruptions. There was an occasional divorce or a parent traveling for business. There wasn’t that specter of CPS. So things just felt more open there between families, kids, and teachers.

There has been a movement in the K-12 setting to have more frank conversations with kids about what’s happening in their home lives, what’s happening in the world. Did the preK teachers feel unequipped to have some of those complicated conversations? How could it have been better?

These are early childhood teachers, they understand a lot about children. I just think we have a cultural idea that, especially kids under 5, are so moldable that we can shape their feelings about things, that they’re not going to have their own feelings. So if we avoid bringing up challenging things, they won’t be as real to kids.

There is research showing that kids do notice. They notice class inequality. They notice racial inequality. Some of these things happening in kids’ lives at home, they might cause personal harm, the kids may feel sad about them, but sometimes they are just facts of life to those kids.

The change I’ve love to see is preschool teachers being comfortable — if a kid is bringing something up — at least [talking about] that.

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.