Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

As a kid, Morgan Patel was good at math and science in school. But she never liked how problems in those classes often had just one answer.

It was the intense, but meaningful, discussions that social studies provoked that drew her in.

“You’re talking with humans about humans and how they interact,” she said. “I just love talking about humans and how they’re imperfect.”

So it’s fitting that Patel, now in her 11th year teaching high school in Maryland’s Montgomery County Public Schools, does that on a daily basis in her Advanced Placement Human Geography class.

It’s a course that delves into where humans live in the world and why, with units examining how that’s shaped everything from culture and religion, to language and politics.

The class can be heavy. Even before this year, Patel taught about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, as well as The Troubles in Northern Ireland, the violent partition of India and Pakistan, the decades of fighting that led to the formation of South Sudan, and the ensuing civil war. The class includes other topics that can be difficult to discuss, too, such as human trafficking, gender-based violence, and food insecurity, including in the U.S.

Patel, who holds a prestigious National Board Certification teaching credential, says it’s her goal to help students wade through polarizing topics — by bringing in historical context, and not leaping to conclusions — so they can do the same when they consume media about these subjects on their own.

“Even though it’s tough to teach this,” she said, “I feel lucky to teach it.”

Patel spoke with Chalkbeat a few days after the most recent ceasefire between Israel and Hamas ended about how she approaches complicated subjects like the Israel-Hamas war, the ground rules she sets for respectful class discussions, and why she asks her students to document their slang each year.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Your class teaches about the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Before this year, how would students interact with that history?

I teach in a very diverse school. It absolutely has kids with family in one of those places sometimes, or they might be Muslim, Arab, Jewish, or Israeli. I’ve even had both [Muslim and Jewish students] in the same class before.

Even before this year, they would see things on the news or they’d hear from adults that this is a really bad conflict, but they wouldn’t understand why. So I always spend a lot of time on the why.

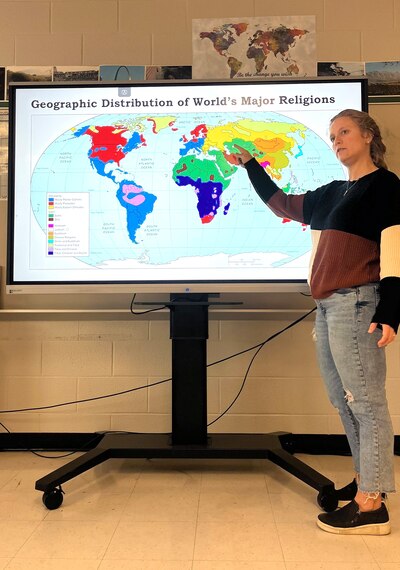

I use a lot of videos and maps. I show a picture of Jerusalem and I show how it’s divided into quarters. And I show a picture of the mosque, the Western Wall, and the major Christian church, and how they are all literally on top of each other. And then I use maps of the land over time — the Palestinian lands and Israeli land changing, depending on political or cultural events.

History doesn’t always have this visual component. It makes it much easier to grasp what’s going on.

We use a lot of geographic data, like looking at life expectancy or the unemployment rate in Palestine versus Israel. There is also a great video from a series on YouTube called “Middle Ground.” The kids can see both sides and see that there are biases on both sides, but that there are also people who are willing and trying to make this conflict better. Which I think is important for them to see.

When students better understand this conflict, how does that help inform what you do later in the curriculum?

Once they learn how to read a map, and the data on that map, they understand that the key is picking up on spatial patterns. You look at data of Jerusalem, and who lives there, and you immediately see how diverse it is and that that can cause issues between groups of people who all say that’s their land. And are all not wrong. This conflict is not different from many other ones in that same pattern.

How do you handle discussions about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in class?

More than others, the students who have an opinion [about this conflict] are very set in that opinion. So it’s not like other topics where we might have a discussion or a debate and there is an attempt to convert people to the other side.

We set ground rules, as I always do for a tough conversation. It’s always: Be an active listener. Try not to generalize your experience. You are an ‘I,’ you’re not a ‘we.’ Ask questions when you don’t understand. Make sure you are trying to understand the other side, instead of talking over them or assuming what you know is right.

You don’t have to agree with someone, but you have to respect them. If you can’t be in here, or you can’t be doing this, take a walk, or tell me. I can usually pick up on when it’s getting a little intense for someone.

You don’t have to participate at all. Sitting there and listening is participating. I never force them to talk. This would not be the kind of thing where you should do random calling.

You’re about to teach the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in your class this year. Is there anything you’re going to focus on more than in the past?

Something new this year that I’ve never focused on as much is how to consume media. [Students] need to realize that sometimes, for your own mental health, it’s OK to step away from social media. But then, if you are going to be in it, know what you’re getting into and know how to consume it properly so you’re not overwhelmed.

I am more nervous than in past years to talk about this conflict. I usually leave open time for questions, which I will probably do, but I don’t want it to turn into a really contentious discussion. I just feel like it could end badly if I allow an open forum. So maybe we’ll switch to some kind of individual processing [such as writing or drawing]. I think a moment of breathing and thinking through on your own might be great.

[In past years], I always explain to them: I am severely summarizing something way more complicated, and I’m not telling you all the players. But because they’ve now seen the actions taken by Hamas and [the Israel Defense Forces], I think I am going to go more into that, defining who those groups are. I’m going to talk more about the actual current conflict — the attack starting it and the retaliation after that, and then the [temporary] ceasefire. I don’t know yet if I, or they, can handle showing videos.

You said you’re feeling a little bit more nervous to teach this than in the past. As you’re getting ready to teach this unit, how are you thinking about that?

In the past when I taught this, by this point, they would know my thoughts on religion and my own religion. They would know that I am not on either side of this conflict. I am a very unbiased third party is usually what I’d call myself.

But my issue this year, as I’m gearing up to teach this, I’m finding it more and more difficult to stand there and be unbiased. I am not going to shy away from showing the injustices that are happening, especially in Gaza. I’ll just try to go about it as unbiased as I can, but ignoring it is also not unbiased.

I think what might be important, which another teacher showed me, is adjusting the way you think about this. We’re very much taught to be like: OK, this is right, or that is right. When really there is gray area here, and it’s OK to see why both sides are wrong and both sides are right in different ways. We’re not looking to choose sides here. We’re showing injustices that are happening on both sides.

The conflicts you teach often aren’t taught in other classes, so this might be the only time kids are learning about it.

Right, they’ll briefly have it mentioned to them, but it’s never explained. I love that I get to teach a course like that, but it’s also a lot. These are civil wars and genocides. You have to go about it with an open heart and open mind. I know my students very well, but I sometimes have no idea they have a connection to a certain place I’m talking about.

Do you have a favorite lesson that you teach each year?

The culture unit, in general, is my favorite. Within culture, we talk about language, and origins of language, why different languages are where they are. As part of that, we talk about dialects. We talk about code-switching and how most of us change how we speak based on age, race, etc.

I have my students make a teenage slang dictionary as their dialect. I’m putting it together right now. It gives them a chance to be their true selves. I’ve saved it over the years; it’s kind of like a time capsule into how language, and how slang, changes.

Do you show them the old versions?

I was just doing it [a few] days ago. They were like: We don’t say that anymore!

What’s really cool is sometimes it’s the same word, but it’s just changed over time, and they have to redefine it in the 2023 version. It’s very realistic, and they enjoy that.

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.