Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news organization covering public education in communities across America. Sign up for our free newsletter to keep up with how public education is changing.

Lawmakers across the country are moving to make it easier to kick disruptive students out of school, a get-tough turn toward stricter discipline that reflects mounting fears about school violence and disorder.

The proposed state laws follow a pandemic-era surge in school gun violence and student misbehavior that some parents and politicians have blamed partly on lenient discipline policies. Proponents, including lawmakers from both parties and some teachers, say the new measures are needed to restore safety and order in schools.

“School violence is on the rise across the state,” Isau Metes, advocacy director at Nebraska’s teachers union, told lawmakers last month. She said a bill authorizing educators to physically restrain and remove disruptive students would enable teachers “to protect the other students in the classroom.”

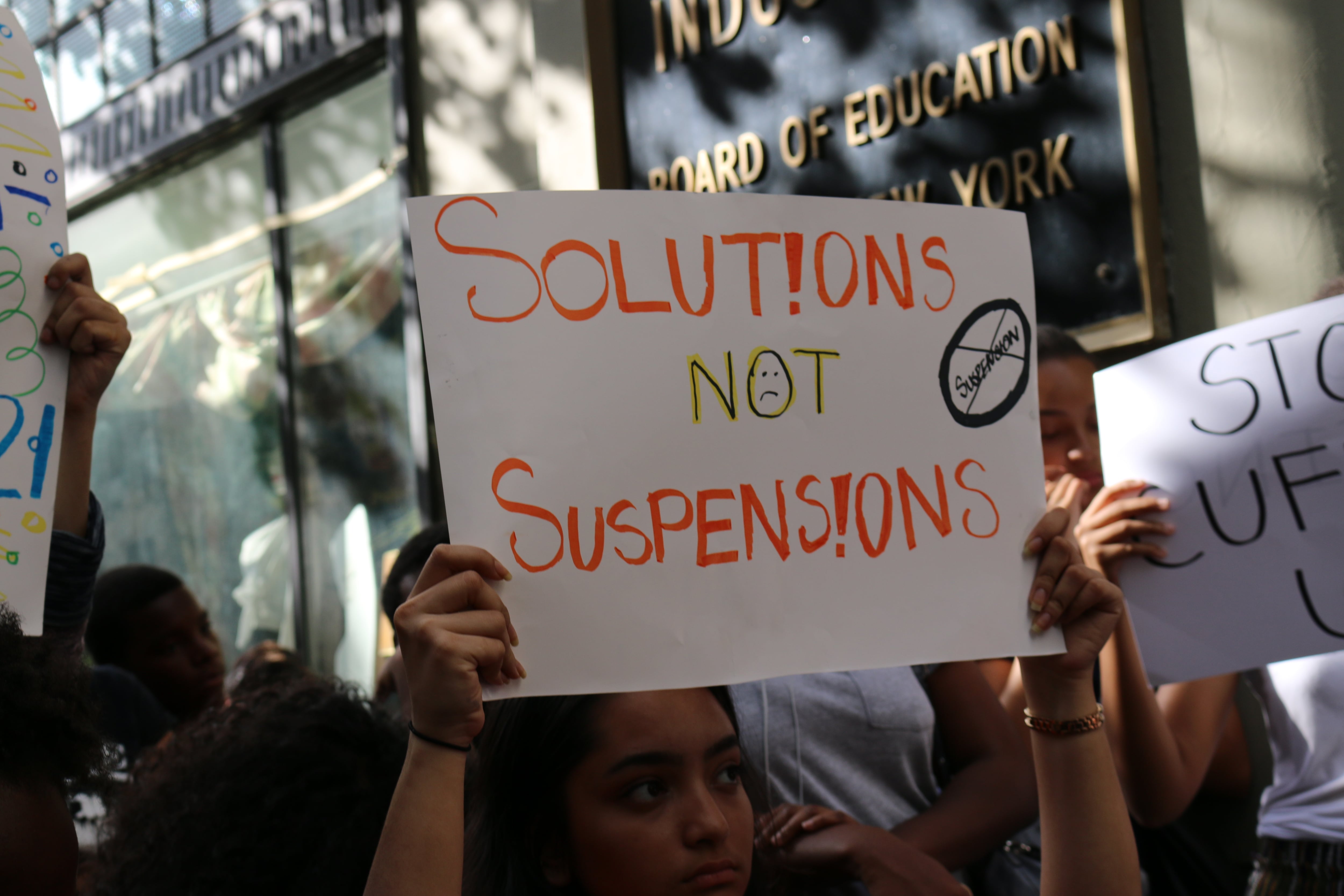

But critics say the proposed state laws would punish young people still recovering from the pandemic and trigger a return to zero-tolerance discipline that could be disastrous for students of color and those with disabilities.

“We know that the things that are being proposed are ineffective, will harm children, and will not contribute to the safety of schools or improve behavior,” said Russell Skiba, a school psychology professor at Indiana University who studies school safety and discipline.

Filed this legislative session, the measures aim to crack down on a range of student behaviors — from simply talking back to teachers to attacking classmates or staffers.

A bill advancing through the Florida legislature would empower teachers to remove “disobedient” or “disrespectful” students from their classrooms and to use “reasonable force” to protect themselves and others. A proposed Texas law would allow teachers to eject disruptive students after a single incident, while a North Carolina proposal would permit long-term suspensions for cursing and dress code violations.

A West Virginia bill, which the state’s House of Delegates passed last month, lets teachers force “disorderly” students out of their classrooms, with multiple removals triggering an automatic suspension. Proposed laws in Arizona and Nevada would allow schools to suspend students as young as kindergarten. Last week, Nevada’s governor pitched his own bill, which would automatically expel students of any age who injure school employees.

While Republicans have led the push for stricter school discipline, many of the recent bills have bipartisan support. In Kentucky, lawmakers from both parties backed a bill allowing schools to “permanently remove” disruptive students and place them in alternative settings, including online programs. The state’s Democratic governor signed the bill into law last week.

The bill “really comes down to school safety,” said Gov. Andy Beshear, “at a time when we’ve seen some really scary incidents across the country.”

Teachers support push for tougher discipline

Teachers unions have championed some of the proposals.

In Nevada, the state union said the legislation is necessary to protect educators, who have expressed “alarming concerns about personal safety.” Clark County, the state’s largest school district, was rocked by several incidents of student violence last year, including the brutal attack on a Las Vegas teacher for which a 16-year-old student was charged with attempted murder.

The Nevada bills would roll back a 2019 law that required schools to adopt “restorative justice” practices, which aim to replace suspensions and expulsions with mediation and relationship building. The approach has gained popularity over the past decade, with more than 20 states passing laws that promote restorative justice, according to an analysis by the Center on Gender Justice & Opportunity at Georgetown Law.

The bipartisan bills would repeal parts of the 2019 law that forbade students under age 11 from being suspended or expelled except in rare cases, and that required schools to create restorative plans for students before removing them. Republican Gov. Joe Lombardo’s proposal would also free the state from having to develop restorative justice guidelines.

The bills’ supporters say the 2019 reforms have deterred schools from disciplining unruly and even violent students, which erodes safety and disrupts learning. In one of many letters from educators backing the new bills, Las Vegas teacher Kristan Nigro wrote that her school took little action after one of her kindergarten students hit other children and threw scissors at the teacher.

“It is not fair that a student can walk into a classroom and be violent and disruptive without any consequences,” wrote Nigro, who is on the leadership council of the Clark County teachers union. She blamed the lax discipline on restorative justice, calling it “just a fancy buzzword and a complete failure.”

But other educators say most schools never fully enacted the discipline reforms due to inadequate training and resources, making it difficult to address the underlying issues that can cause students to act out. Machelle Rasmussen, a social studies teacher in North Las Vegas, said her high-poverty high school has nearly 3,000 students but no social worker.

“To do restorative justice properly, you have to have the resources,” she said in an interview, adding that she opposes the new bills. “Just saying, ‘Permanently expelled, go away,’ that doesn’t make the problem go away. That doesn’t help that child.”

Critics say harsh discipline feeds school-to-prison pipeline

A similar debate to the one in Nevada had been simmering nationally for years before reaching its recent boiling point.

In 2014, the Obama administration issued guidance urging schools to reduce suspensions and embrace alternatives, such as conflict resolution, peer mediation, and counseling. The guidelines also warned that schools could face federal investigations if data showed racial disparities in how frequently or harshly students are disciplined.

Federal data has consistently shown such disparities, with Black students making up 15% of public school enrollment but receiving nearly 40% of suspensions and expulsions in 2017-18. Other studies have found that Black students are punished more harshly than their peers for the same offenses.

Students who get suspended tend to have lower test scores and higher dropout rates, and students who attend schools with high suspension rates are more likely to be arrested and incarcerated as adults — what advocates call the school-to-prison pipeline.

In 2018, the Trump administration rescinded the Obama-era discipline guidance, a move that many education and civil rights groups opposed. Critics of the guidance and the push for less-punitive discipline said it hamstrung schools, encouraged rule-breaking, and even increased the likelihood of school shootings.

The Biden administration said in 2021 that it would review the issue, but has yet to announce whether or not it will reinstate the guidance. On Friday, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona released a letter opposing corporal punishment in schools, along with tips for promoting safe and supportive schools.

With the new bills, state lawmakers are insisting that educators should be free to discipline students as they see fit.

“There’s a very strong political argument for this as a way for Republicans to be on teachers’ sides,” said Max Eden, a research fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute who has written about school discipline. The bills send the message that, “We trust your discretion when dealing with student behavior.”

But civil rights advocates note that Black students are more likely than their white peers to be disciplined for subjective infractions, such as defiance or disrespect. They worry the proposed laws will worsen racial disparities by allowing schools to remove students for loosely defined “disruptive” behaviors.

If lawmakers want to make schools safer, they should ensure that students have access to mental health services and programs that teach positive behaviors, said Morgan Craven, national policy director at IDRA, an education civil rights group.

She added: “Our response should not be, ‘OK, let’s just find faster, easier ways to simply kick them out.’”

Patrick Wall is a senior reporter covering national education issues. Contact him at pwall@chalkbeat.org.