This story was co-published with USA Today.

Kirstin Smith was worried after her 5-year-old had a traumatic interaction with another student at school this past fall.

Her daughter’s behavior had changed — she was hiding under desks at school and waking up scared from her nightmares. Smith wanted to get her some help.

A couple months later, the kindergartner was sitting cross-legged on her mother’s bed, chatting with “her lady” on a laptop screen while Smith stirred macaroni in the kitchen. Every so often, Smith pressed her ear to the bedroom door or cracked it open to check in.

The virtual therapist met weekly with Smith’s daughter for the next three months, teaching her how to breathe deeply to stay calm and when to seek help from a trusted adult.

“I am happy that she was able to build that relationship with her therapist remotely,” Smith said. “When she gets overwhelmed, she knows that she’s overwhelmed, versus her feeling like she did something wrong or something is wrong with her.”

The number of U.S. students with access to virtual mental health support has skyrocketed over the last year. Thirteen of the nation’s 20 largest districts have added teletherapy since the pandemic began, expanding access to hundreds of thousands of students, a Chalkbeat review found. That includes Clark County schools in Nevada, where Smith’s daughter attends school. Two more big districts plan to add the service later this year.

The rise of teletherapy is a reflection of the intense pressure schools are under to address a youth mental health crisis that shows no sign of waning. The services offer a way to reach more students without bringing on full-time staff that are often difficult and expensive to recruit. And while some educators and parents have been skeptical of the virtual setup, many say they’ve since been won over.

“This does eliminate barriers,” said Nirmita Panchal, who’s written about the growth of tele-mental health in schools for the nonprofit KFF, which conducts health policy research. “There are definitely some challenges, but big picture, we do see the advantages in linking students who otherwise wouldn’t have care into care.”

Schools see benefits to teletherapy

School leaders say the wait time to see a therapist virtually is often days, instead of weeks or months. Teletherapy can get help to more kids with moderate needs, who often don’t get seen at school because staffers are focused on kids in crisis. It can also bring some relief to kids with bigger challenges while they wait for more intensive in-person care.

And it’s often easier to match a student with someone who speaks their family’s language or is of a particular race, gender, or cultural background when schools have access to a larger national pool of therapists.

That helped persuade Ellen Wingard, who oversees student support services for the schools in Salem, Massachusetts. Her district started offering teletherapy through a local mental health center and the company Cartwheel in January. Initially, she worried it would be “a waste of time.”

“I was very hesitant,” she said. “I was like: ‘Our kids do not want to do that.’”

But she’s been impressed by how the teletherapy has reached students who never got past a referral from their school counselor to seek help outside their school before. School staff have come to her in surprise, saying: “Wait, they what? They found a male counselor?” Wingard said.

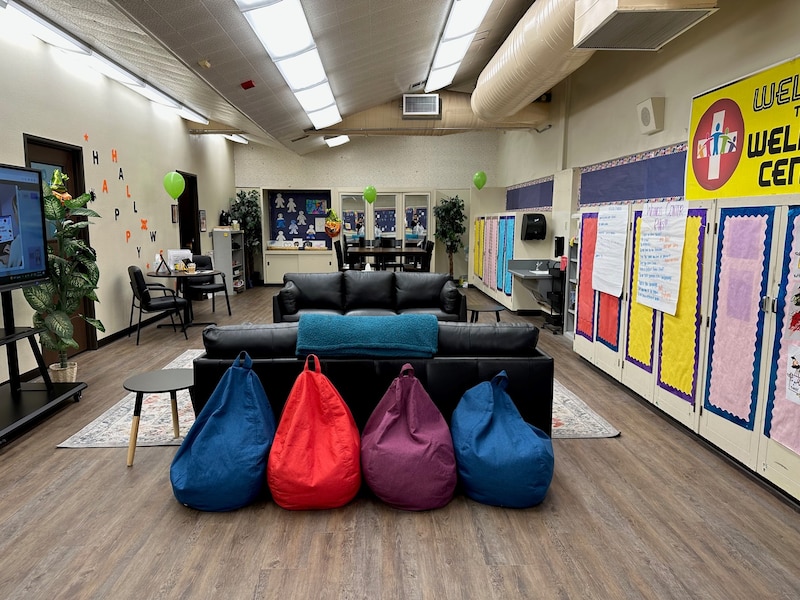

Another upside is that schools can offer teletherapy to students at home or on campus. Some families like that they can easily supervise their child and check in with them after a session at home. At school, students typically go to a private space where they can slip on headphones and talk with a therapist on an iPad while a nurse or counselor supervises nearby. Then they can return to class without much disruption to their day.

“It’s not for everybody, but for those students and parents who want that, it’s been fantastic,” said JaMaiia Bond, who oversees student mental health services for Compton’s schools in California, which started offering teletherapy through Hazel Health this school year.

The San Francisco-based company has become the top player in providing teletherapy to the nation’s largest school systems. By this fall, Hazel will be working with half of the country’s 20 biggest districts.

Nationally, since Hazel launched its tele-mental health service last school year, the number of students who can access teletherapy through the company has shot up from just under a million students at 20 districts to more than 2 million students at 70 districts, according to a Hazel spokesperson — a figure that does not yet include a new $24 million teletherapy initiative for students across Los Angeles County.

Schools spend millions on virtual mental health support

Among Hazel’s clients are Clark County schools in the Las Vegas area, which spent $2.6 million on teletherapy over the last two school years, records obtained by Chalkbeat show. Hawaii is spending $3.8 million on Hazel’s virtual therapy over three years, while the Houston school district set aside $5 million for teletherapy and virtual primary care services over the next five years. Fairfax County schools in Virginia are expected to spend nearly $700,000 on Hazel’s teletherapy. And Hillsborough County schools in Florida are launching a two-year $2 million teletherapy initiative through Hazel this fall.

Others have stayed local. Some Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools offer teletherapy through a local hospital funded by a $10 million donation. And Mississippi is offering teletherapy statewide through the University of Mississippi Medical Center. The initiative is funded by $17.6 million in federal COVID relief dollars.

That money helps cover equipment, training for school staff, fees, and in some cases, the therapy. Mississippi, for example, is covering the full cost of students’ sessions to avoid insurance headaches for families.

There are some drawbacks and limitations. Younger children and some students with disabilities may find the technology difficult to use, educators say. In Mississippi, some districts decided not to offer teletherapy because they were worried about overburdening their few school nurses. And some districts prefer to connect students to local mental health professionals.

“They understand the community,” said BJ Wilson, the interim special services director for Grandview School District in Washington, which is weighing whether it wants to hire Hazel to offer teletherapy. “That’s really important to say: ‘I live three blocks from you, I know exactly what you’re talking about.’”

Some also worry that expanded access to teletherapy could reduce the urgency to offer students in-person care, which many kids need or prefer. That’s especially true for families that lack a stable internet connection at home, or don’t have a quiet, private space for kids to meet virtually with a mental health professional.

Getting families on board can also take work. Generally, schools must obtain consent from a legal guardian to offer teletherapy to students, though in some states students can consent to mental health treatment themselves.

In Houston, Diego Linares has been hosting “coffee with the principal” events so he can show families how to sign up for his high school’s new teletherapy offering through Hazel. He makes sure parents know the teletherapy is always free to their children and that immigration officials won’t see anything they share.

“When your immigration status is important for you and you worry about it, you don’t want to put your name on things that may get you in trouble,” Linares said. “This is important for them to understand that this is really for the benefit of the students.”

Will teletherapy disappear when COVID funds run out?

Whether schools will offer teletherapy long term remains an open question. Some in Congress want to create more permanent funding, but right now many school districts are relying on temporary COVID relief funds.

Student usage will likely be a determining factor. Right now, numbers tend to be small as many programs are just getting started.

Hawaii’s schools referred almost 1,000 students for virtual mental health support between last August and mid-March, said Fern Yoshida, who oversees the teletherapy initiative for the state education department. That’s less than 1% of Hawaii’s students, but Yoshida said they’re comfortable with that number for now, since it represents students who otherwise may not have gotten help.

“We’re going to evaluate to see how this goes,” Yoshida said. “But we’ve been finding that this has really fit.”

Some students who’ve turned to teletherapy see promise in the service.

Eighteen-year-old Fatima Magallon found out that her Las Vegas high school was offering teletherapy when Hazel paid students there a small stipend for their ideas on how to improve the company’s service.

Not long after, Magallon’s grandmother died. Magallon’s grades started dropping, and when a school counselor told the senior she may not graduate on time, she decided to give the teletherapy a try.

The initial sessions were awkward, Magallon said, but eventually she felt like she could open up. It was especially helpful when the therapist tried to make it feel like they were together in person.

“She would open her blinds and I would open mine,” said Magallon, who graduated last June. “Seeing light through the Zoom, it actually helped a lot.”

Kalyn Belsha is a national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.