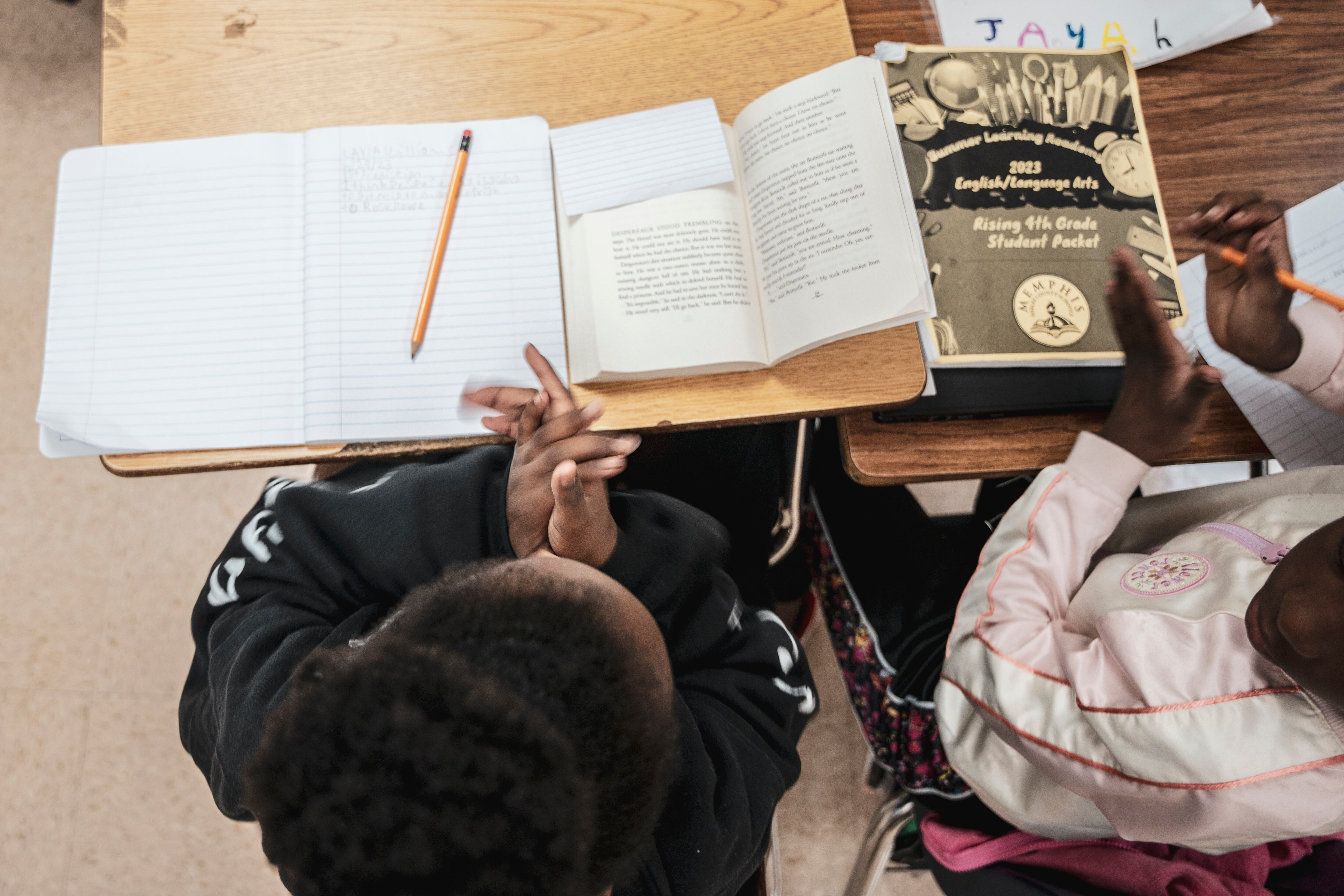

Summer school might be more popular than ever — at least among educators trying to address unprecedented declines in student learning.

With the help of COVID relief money — some of which was earmarked for this very purpose — schools across the country have expanded learning opportunities over multiple summers. Officials say summer school is no longer just for kids who need to make up classes to move up a grade, but for a broader swath of students who have fallen behind since the pandemic began.

So has summer school worked as a learning loss recovery strategy?

A new study, the most comprehensive analysis to date of pandemic-era summer learning, says the answer is: kind of.

Students who attended school over the summer of 2022 saw their math scores improve, according to the research. This offers some of the first concrete evidence that a key learning loss strategy is working. However, those gains were modest, and there were no improvements in reading. And since only a fraction of students went to summer school, it barely made a dent in total learning loss.

Overall, the latest research suggests that some catch-up efforts are paying off, but may be insufficient to return students to their pre-pandemic trajectories.

“It’s a glass-half-full, glass-half-empty story,” said Dan Goldhaber, coauthor of the study and a professor at the University of Washington. While summer school had a positive impact, he said, “only a small slice of the damage that was done from the pandemic is recovered from summer school.”

Summer learning helps, but benefits are modest

The new research, released by a team of scholars with the education research group CALDER, examines the impact of summer school last year in eight districts, including those in Dallas, Portland, and Tulsa.

Summer programs varied from place to place, but they typically ran between 15 to 20 days, with an hour to two of academic instruction each day. Districts usually allowed anyone to participate, but also targeted invites to struggling students. Summer school was open to students in elementary and middle grades, and, in a few places, high school.

Somewhere between 5% and 20% of students participated in summer school, depending on the district. Goldhaber noted that some districts had open spots, perhaps indicating low demand among families or insufficient recruitment efforts. Participating students attended about two thirds of the time — highlighting the perennial problem of absenteeism in summer school.

On the more encouraging side: Summer school students were more likely to be struggling academically, suggesting that officials were successful in recruiting kids who were most in need of extra learning time.

Researchers compared test scores of summer school students versus similar kids who didn’t attend over the summer. To start the next school year, summer school students had slightly higher scores in math, though not reading. There was clear evidence of math gains in five of the eight districts.

“The simple takeaway is something’s working,” said Goldhaber.

The researchers note that it’s possible that those students made more gains not because of summer programming, but because their families were more motivated to help them catch up.

Still, the new research offers some support for one of the most common learning-loss recovery strategies since the pandemic began, including over this most recent summer.

Newark Public Schools, for instance, required 10,000 struggling students to attend summer school this year, double that of last year. The district is selling it as an extension of regular schooling. “We’re working to engage parents and make sure they understand that their kids aren’t done just because it’s summer,” a summer school principal previously told Chalkbeat. “If you miss school, we make calls.”

Denver launched a “summer connections” program which focused on “accelerating” students by providing instruction for their incoming grade level, rather than reviewing material. An internal analysis found, unlike the CALDER study, that participating students did not make noticeable test score improvements compared to those who didn’t go to summer school. (Teachers and parents did say that students had made social growth, and nearly all students said they had made friends in the program.)

But even when it is effective, summer school can only go so far in making up pandemic-era learning loss.

The CALDER researchers estimate that summer learning closed only 2% to 3% of the pandemic-induced learning gap in math. In other words, the impact, relative to the size of the problem, was tiny. This reflects the fact that summer school is, by its nature, limited in scope. Summer learning added only a small bit of time for a small fraction of students.

The researchers say that summer school could close the math gap only if every student attended over multiple years. This would amount to extending the school year — an idea that has not proven popular with school officials or parents.

Schools have also added staff, tutoring programs, and after-school time, among other catch-up efforts. To date there is limited research on the efficacy of these approaches. Some of them, particularly online tutoring, have faced challenges reaching struggling students.

Data from the testing company NWEA through the end of last school year found that students remain substantially behind where they would be if not for the pandemic. Results from a handful of state tests also show that students remain behind, but suggest that students in some states have been catching up to pre-pandemic levels.

Matt Barnum is interim national editor, overseeing and contributing to Chalkbeat’s coverage of national education issues. Contact him at mbarnum@chalkbeat.org.