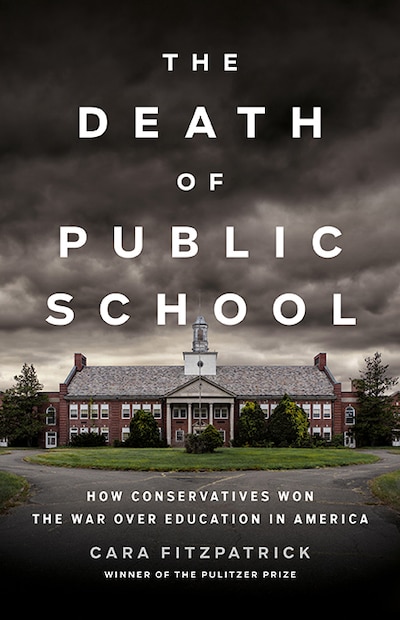

Journalist Cara Fitzpatrick offers a dramatic thesis in the form of the title of her new book, “The Death of Public School.”

In it, Fitzpatrick chronicles the history of school choice in America — a decades-long political effort that she says has culminated in victory for its advocates. Charter schools have grown rapidly. More states are using public money to help parents pay private school tuition. The pandemic combined with a backlash against school curriculum on race and gender have energized this effort.

Fitzpatrick is agnostic on whether this shift has been a good thing for American education, but she’s convinced that it’s a big deal.

“The war over school choice has been the fiercest of this country’s education battles because it is the most important: it is a struggle over the definition of public education,” she writes. “These thorny questions — about what type of education the government should pay for, whose values are reflected in schooling, and what these issues mean for society and democracy — have been waged since the country’s birth.”

Chalkbeat recently spoke with Fitzpatrick, who as a reporter for the Tampa Bay Times won the Pulitzer Prize for documenting the resegregation of schools in Pinellas County, Florida. Currently, Fitzpatrick is a story editor here at Chalkbeat (and a valued colleague of this reporter). She did not play a role in selecting questions for this interview or editing it.

Chalkbeat asked Fitzpatrick about the early history of school vouchers that started with resistance to desegregation; the more progressive arguments for school choice; choice advocates’ recent focus on culture war issues; and how the title of her book could be true when most students still attend a public school.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me why you wrote a book about the history of school choice. What interested you in this topic?

I was a reporter in Florida, and I had written a lot about segregation. As part of that, I spent some time following families around who were leaving these segregated, low-income public schools. In Florida, there’s a lot of choice options, so I often encountered families who were moving to a charter school, or they were going to a private school with a voucher, or maybe they were going to a magnet public school. One of the questions that I had was essentially: Were they finding better choices?

Let’s start with the early parts of this history, where you start the book. Can you talk about the role that school choice played in resistance to desegregation starting in the ’50s?

In the few years before Brown v. Board of Education, and then after Brown, there was an effort by segregationists in the South to get around desegregation by using a variety of mechanisms, including school vouchers. It varied in states, but it was basically an effort to abandon the public schools and use state support to prop up entirely white private schools. But it was ultimately unsuccessful, because the courts were united in striking down every attempt that was made, including the voucher programs.

Some school choice critics still use this history to attack the concept of school choice, especially private school choice. Do you think that’s fair?

I don’t know that it’s a reasonable critique of what’s going on now. What I ended up finding, and thought was compelling, was that at the same time that segregationists were using school vouchers to try to exclude Black children from receiving a fair education, there were other voices in there who were viewing school vouchers in a very different way.

Economist Milton Friedman gets credited as the father of school vouchers. He was looking at it as an economic tool. Virgil Blum was a priest in Milwaukee who was interested in vouchers for religious liberty, because he thought that it was discrimination against religious families who had to pay taxes for a public school system and then also pay tuition for private religious education.

It was really striking even in the years that the courts were striking down school voucher programs in the South, progressive voices were also raising this issue of school vouchers as a tool of empowerment. Kenneth Clark, who was involved in Brown v. Board, was one who raised that idea.

So I think understanding that is crucial for having a good sense of whether or not that’s really a fair charge to make against contemporary advocates for school choice.

Can you elaborate on why Kenneth Clark, who was a Black psychologist who testified in Brown v. Board and was cited by the Supreme Court, was interested in school choice and school vouchers?

He was disappointed in the years following Brown with how integrated school systems were working out, not just in the South, but in the North, where many school systems were just as segregated. He was looking for different ways to improve education for Black students. It wasn’t just vouchers. He also made some recommendations that sound a lot like what charter schools are today, which I thought was really interesting to see that far back.

What happened to the idea of private school choice in the decades after desegregation?

So the court struck down the school voucher programs in the South, and then it’s kind of just in the realm of theory for a while — it’s people basically debating it.

Milton Friedman keeps alive his economic argument, which was for every kid regardless of income to have a voucher. Harvard professor Christopher Jenks has an idea of targeted vouchers for low-income children, as a tool of empowerment. There’s a small, sort of failed effort by the federal government in California to try out vouchers.

There was a pretty solid push from a number of quarters in the ’60s and ’70s to provide some kind of government aid to religious schools, especially Catholic schools, because they were struggling during that time period. That didn’t end up going anywhere meaningful.

In the ’80s, President Reagan was an advocate for vouchers. That also didn’t really go anywhere. Then the first modern school voucher program happens in Milwaukee in 1990. That’s when you start to see the beginning of this latest era.

Your book has many characters, but to me if there was a main character, it was Polly Williams. Can you describe her and her role in the school choice movement?

Polly Williams was a Black Democratic legislator in Wisconsin. She was kind of a contrarian. Probably the best explanation for her would be that she was a Black nationalist. She was very interested in education in Milwaukee, and she was very concerned that Black students were not being well served by the Milwaukee school district. She tried legislatively to do a number of different proposals to help Black students in Milwaukee. She was shot down at just about every turn, and so became kind of frustrated with Democrats, with her own party, and willing to look at alternatives.

That’s when she and Tommy Thompson, who was a white Republican governor at the time, became allies on the issue, and were able to successfully push through a small experimental voucher program in Milwaukee.

Walk me through Polly Williams’ evolution on her thinking about school choice.

Polly Williams had a very particular view about vouchers — this progressive model very much for low-income children, Black and Latino children, very much as a form of empowerment. She viewed it as being somewhat small and experimental and intended for a particular group of kids.

She became disillusioned with some of her conservative allies who had different ideas about what choice should be like and who it should be for. She was concerned when religious schools were allowed to participate in the program, because religious schools had more white students. She feared that a program that was largely for Black students might also change to be more of a benefit for white religious families and especially ones who could already afford to pay tuition.

Do you see Polly Williams’ vision for school choice as the opposite of white Southern sector segregationists’, or was it the other side of the same coin?

She viewed it as something that was meant to aid children who were the least well served by the school system, which is different than saying we want all white kids to be separate from all Black kids. That’s not what she was about.

She was, however, very unapologetic about being focused on helping her race, and what she viewed as her people. As a Black nationalist, she thought that integration policies were harming Black kids. She thought that it was taking power out of Black neighborhoods when you had kids bused all over.

Can you talk about when charter schools entered the equation, and why they have been, at least until recently, more politically successful than private school vouchers?

In the ’90s, those ideas were kind of coming up at the same time. Milwaukee’s voucher program passed in 1990, and the first charter school law was in Minnesota in 1991.

I think one of the reasons that charter schools took off was because they were meant to be public schools. It was appealing because it was an alternative to school vouchers, and so it gave Democrats something that they could hold up to say: We are for choice, but we’re for choice within the public school system. Republicans also backed charter schools as maybe not as great as school vouchers would be, but something they also could get behind. So charter schools enjoyed bipartisan support for a long, long time, and that helped the ideas spread all over the place.

It actually seems like the charter school movement was detrimental to the private school choice movement by sucking up some of the political oxygen.

I think that’s mostly right. I think charter schools were just an easier thing to support in some ways, and because there were fewer legal questions, I think that helped propel them.

But in some ways, charter schools are more far-reaching, creating totally new schools, and have been much more disruptive to the traditional public school system than private school choice.

I think that’s true for a period of time — we’ll see how this current wave of choice legislation plays out. But you see that especially in urban areas, and people grappling with what does this mean for the public school system, if suddenly 20%, 30%, 40% of kids are going to charter schools. But it varies so much, because you do have states where they pass a charter school law, but then the law itself was so restrictive that you didn’t have the same explosion of charter schools.

Can you describe how the school choice movement has changed since the start of the pandemic, and why it has been so successful in getting a string of far-reaching private school choice programs passed?

The pandemic gave Republicans a moment politically where there are discussions happening about education. There are parents who maybe are exploring other options for their kids or did for a period of time during the pandemic. It gave Republicans room to seek expansions and pass new programs.

There’s also an argumentative shift happening during the pandemic where we saw advocates go from talking about school choice as a civil rights issue to embracing school vouchers for everyone. This idea that it’s really about parental freedom and about values has taken off. And Republicans are going on the attack against public schools and embracing this idea of using the culture war to win policies for choice.

Let’s talk about your title: “The Death of Public School.” How can public school be dead if the vast majority of students still attend a traditional public school?

I liked that title because I was thinking about, what is this ultimately about? What is the argument that people are having? And why is it such a heated argument? I was thinking about: Can these things coexist? Can you have a robust traditional public school system, and also have state dollars going to private education, especially in greater and greater numbers?

Ultimately, it’s about what happens to the public school system and whether or not it thrives or is diminished in some way by these programs. I felt like the current moment in time was pointing in not a great direction for the public school system.

I also had kind of a wonkier question in mind, which was: What is a public school ultimately? I tried to trace that idea in the book. Republicans really were pushing for a definition of public education that is quite different than the traditional one. Republican governors say right now that any education paid for with tax dollars is public education.

One response to the title would be that the empirical research doesn’t support the idea that the expansion of private school choice kills or even harms public schools.

I don’t know if we know what the effects of this current wave of private school choice are going to be when you’re talking about having every student in a state be eligible, including kids whose families were already paying for private education. We’re seeing numbers of participants balloon in places like Arizona, and the cost projections are so much higher than what they had initially talked about in those places. With the universal programs there’s just a lot that we don’t know about how that’s going to shape up.

Do you think the triumph of school choice has been a good thing for American education?

It’s not for me to say if it’s been a good thing for American education. I very deliberately do not take a viewpoint in the book, partially because I think school choice is a fairly complicated and nuanced thing, which is part of what attracted me to writing about it in the first place.

I had some driving questions in the introduction about what does this mean for community, and what does this mean for democracy, and what does this ultimately mean for the public school system. I very deliberately do not answer, because I think those questions are for the reader to think about by the end of the book.

Matt Barnum is interim national editor, overseeing and contributing to Chalkbeat’s coverage of national education issues. Contact him at mbarnum@chalkbeat.org.