Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

Hundreds of schools in two of the nation’s largest districts have stopped offering online tutoring through the company Paper following questions about quality and cost.

Hillsborough County schools in Florida dropped Paper altogether, while around 150 schools in Clark County, Nevada decided not to work with Paper this school year, according to district records obtained by Chalkbeat.

“After evaluating usage rates, return on investment, and student achievement data, we decided not to renew the contract,” Tanya Arja, a Hillsborough County schools spokesperson, wrote in an email to Chalkbeat last week.

Paper has lost other major clients recently, including Boston Public Schools, which cut ties with the virtual tutoring company this summer, a year earlier than expected, after a small share of students used the virtual tutoring.

The cutbacks come as many districts are evaluating which academic strategies to keep — and which to toss — as they head into the final full school year to spend billions in federal COVID relief dollars. The decisions indicate that at least some educators have grown disillusioned with Paper and perhaps opt-in virtual tutoring more broadly.

Some districts are instead investing in regularly scheduled virtual or in-person tutoring sessions during the school day, following the high-dosage model backed by research.

Paper’s online tutoring practices under scrutiny

COVID funding helped fuel significant growth for Paper, a company that landed contracts worth tens of millions of dollars to offer virtual tutoring to more than three million students in districts across the U.S. and Canada. Demand for the company’s services soared during the pandemic as many schools looked to get extra help to their students and had new money to spend.

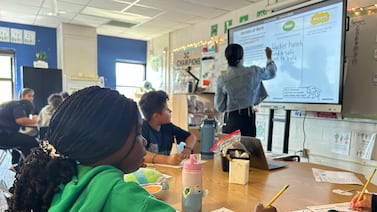

But Paper has come under scrutiny from Chalkbeat and others for often failing to deliver the one-on-one expert help that the company advertises to schools. Some younger kids and struggling students have found the tutoring platform — which looks like a text-based instant messenger with a digital whiteboard — difficult to use. Some districts previously cut ties with Paper after a small share of students logged on for help.

Recently, the company has laid off many of its corporate staffers and tutors, and several top executives are set to depart this month.

In an email, Ava Paydar, a spokesperson for Paper, declined to comment on the changes Hillsborough County and Clark County are making. “We will defer comment to the school districts,” Paydar wrote.

In previous interviews, Paper CEO Philip Cutler defended the quality of Paper’s tutoring, and said the student experience on the Paper platform is always one-on-one because tutors work with students in an individual session — even if tutors are juggling multiple students at once. It’s uncommon for students to be matched with tutors who are unfamiliar with their subject, he added.

Cutler also said that Paper has worked to boost student usage by training teachers and conducting outreach to students and families.

Hillsborough County schools, which serve the area around Tampa, had previously paid Paper around $4 million over the last two years to offer virtual tutoring to 110,000 students in middle and high school. When the district renewed its contract last year, it did so at a reduced price, after raising concerns about low usage. The district had said it would drop Paper if too few students used the tool — and evidently followed through.

Boston school officials cited similar concerns. “For the number of students it was reaching for its cost and our assessment of how it’s been working, Paper has not been worth it,” Max Baker, a spokesperson for the district, wrote in an email to Chalkbeat last month.

Clark County had planned to spend $6.6 million to offer Paper in every school this year, district records show. Schools were told to come up with a plan to get every student in grades 3 to 12 to log on early in the school year.

But the Las Vegas-area district did an about-face shortly after Chalkbeat published an investigation in July that found Paper tutors are often juggling multiple students at the same time and working in subjects they don’t know well — leaving many students frustrated and without needed help. Instead of requiring schools to use Paper, Clark County principals were given the option to keep working with the company or to stop. The schools that opted out serve 102,000 students, or around a third of the district.

Clark County schools appears to have taken public reporting into account while making its decision to cut back on Paper’s services.

The day Chalkbeat published its investigation, a top school official shared the story with Clark County’s superintendent, Jesus Jara, according to emails obtained through an open records request. A few hours later, Jara asked a top academic officer to come see him, then added: “We may need to review this contract and move some funds to FEV Tutors.”

A few weeks later, the school board approved spending $4 million on FEV Tutor, another virtual tutoring company that, like Paper, relies on text-based chat and a digital whiteboard, but has the added feature of live audio for students to speak to their tutors.

In an email, a Clark County schools spokesperson said the district had “reallocated funds previously designated for Paper Tutoring services to include an additional option, FEV Tutor,” but would not say how much the district is now spending on Paper.

Paper also lost a contract with the state of New Mexico earlier this year, after education officials there said the company had failed to get academic help to enough students.

But many other school districts are maintaining their relationship with Paper, which still holds contracts with the states of Mississippi and Tennessee, and several large districts, including Los Angeles Unified and Palm Beach County schools in Florida.

The Washoe County School District in Reno, Nevada agreed to pay Paper up to $2 million to offer virtual tutoring to middle and high school students this school year and last year. The district recently cut back on paying teachers to tutor students after school, justifying the move with the addition of Paper.

“With the introduction of Paper on-line tutoring, in-person tutoring has been reduced,” spokesperson Victoria Campbell said in an email.

In Clark County, Spanish teacher Carmen Andrews will continue to have access to Paper at the Nevada Learning Academy, where she teaches students online.

When Andrews tried the tool last year — a district requirement — she found that some of her high schoolers waited a long time to be paired with a tutor, and some were matched with tutors who didn’t speak Spanish but tried to help anyway.

(Paydar, the Paper spokesperson, said the company always has Spanish tutors available, though acknowledged that mismatches can occur. “While very rare, we find that this type of experience can happen when a tutoring session starts with a focus on one area and then crosses over to Spanish as a subject,” Paydar wrote.)

Andrews sees some value in the kind of virtual support that Paper offers, especially for students whose parents work late in the Las Vegas hospitality industry. This year she’s planning to use Paper to give students extra feedback on written assignments in Spanish. But she’s glad the district gave schools the choice to opt out.

“If a school sees no use for it,” she said, “why pay the money for them to have it?”

Matt Barnum contributed reporting.

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.