When Vicki Sokolik first started working with teens experiencing homelessness living on their own without a parent, she would host “lunch and learns” at local high schools.

Her goal was to explain to social workers, assistant principals, and other staff who qualified as an unaccompanied homeless youth, and how schools could refer those students to her nonprofit for housing and other services.

Sixteen years later, Sokolik says there is still a lack of awareness of these students and their particular social, emotional, and educational needs.

“People still — no matter if they’re in the schools, if they’re lawmakers, if they’re medical professionals — really do not understand what an unaccompanied homeless youth is, or even what to look for,” Sokolik said.

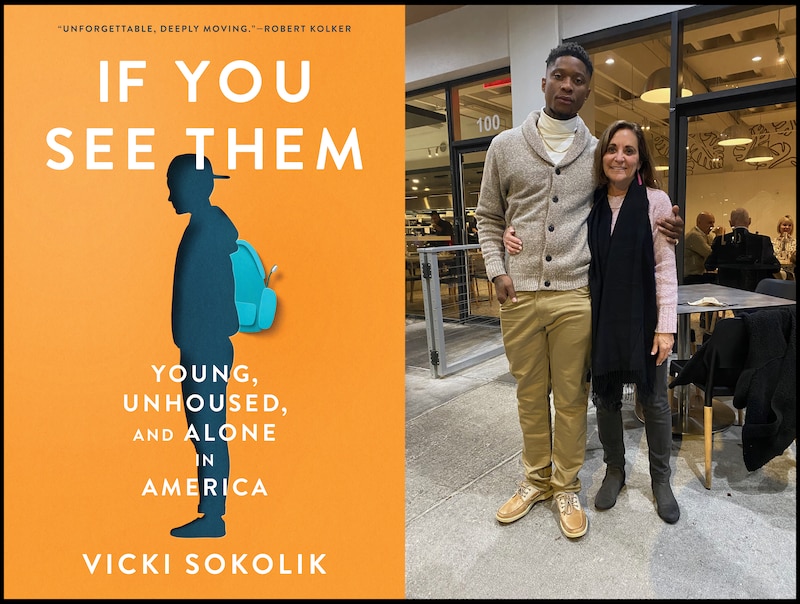

Her new book, “If You See Them: Young, Unhoused, and Alone in America,” details her experience working with these students in Florida’s Hillsborough and Pinellas counties.

The latest federal data show that nearly 111,000 students were identified as unaccompanied homeless youth during the 2021-22 school year — a number many experts and advocates, including Sokolik, say is an under-count. Other estimates that include older teens and youth in their early 20s put the number much higher.

The needs these students have are often great. Many are survivors of rape or sexual assault. Many have experienced suicidal thoughts or attempted suicide. Some were kicked out of their homes because they identify as LGBTQ. Many have had contact with child protective services, but were not removed from their homes. Often they have a juvenile record, sometimes for stealing basic necessities.

It’s also common for these students to be chronically absent from school, and to have undiagnosed learning disabilities. Sokolik recalls one student who entered her nonprofit’s program a few years ago as a 12th grader who could not read. He needed intensive help from a reading coach and a special education plan.

And these students are caught between being treated as children and adults by various legal systems. A student Sokolik worked with lobbied Florida lawmakers to make it easier for youth living on their own to obtain their birth certificate, for example.

Chalkbeat spoke with Sokolik about what she’s learned working with unaccompanied homeless youth through her nonprofit — Starting Right, Now — and what educators should keep in mind.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Why can it be hard for schools to identify students as unaccompanied homeless youth?

This is a very invisible population because the kids actually don’t want to be found. They are so afraid of what will happen if someone figures out that they’re not with their parent or guardian. Will they put them in foster care? What will happen to their siblings? Because of that, they tend to hide.

There’s a lot of shame associated with being a homeless unaccompanied youth. They carry this burden of: They did something wrong. Until they get to the point where they just don’t know what to do anymore, they don’t seek help.

Schools can refer students to Starting Right, Now. What are some of the gaps that your organization is able to fill in that schools can’t?

Unfortunately, schools can’t get to the root of the problem for an unaccompanied homeless youth. The first thing is, obviously, stable housing. So we provide stable housing, we provide food security. We provide academic support, social services support, life-skills training, and then we help the kids plan what their next goal is going to be.

One percent of our kids go to the military, about 9% go to vocational training and the rest go to higher education. And then we provide case management to those kids until they actually get into their career. In addition to that, every single student in our program is matched with their own mentor, so they have this incredibly reliable adult in their life.

You talk in the book about the link between being an unaccompanied homeless youth and chronic absenteeism. What are some of the barriers that prevent the students you work with from attending school regularly?

The kids do what we call couch-hopping, where they’re asking a friend every night: Can I sleep at your house? And a lot of times they’ll get farther and farther away from school. We had a student who was walking six miles each way to get to school. And if it was pouring down rain, she wasn’t going. Transportation becomes a major barrier.

A lot of times, the kids work. And because they have to survive, they end up going to work during school hours. Their employer should not even allow that, but they do. And then the other thing is they don’t have access to laundry facilities. They don’t want to go to school because their clothes are not clean.

The share of students you work with who’ve had a visit from child protective services at some point in their lives is incredibly high. And a lot of them do not have a positive experience with the state. How does that shape the services you provide?

Most of our kids are so afraid of authority, in general, because they’ve watched their parents being taken away. They’ve watched their siblings being taken away. They’ve been taken away.

It shapes everything that we do. When a student walks into our program, we know for sure that they’re not going to trust anything we say or do. And they’re going to probably try to get kicked out because they just know it isn’t going to work out — they already have that in their head.

We have to develop trust by having our actions align with our words, and making sure that when we say we’re going to do something, it’s unquestionably done at the time we say. It takes a long time to build that trust. You have to show up day after day.

We do a lot of activities that require not only them to be vulnerable, but our staff to be vulnerable. We open up with the “Snowballs” activity in the book [which asks staff and students to write down and anonymously share something they’re afraid of, something they’re ashamed of, and something they succeeded at]. When the veil is lifted, I just think that kids realize we’re people, too.

One student in your book writes about feeling like she’s disintegrated, and she’s having these intense feelings of loneliness. How do mental health struggles complicate the lives of the students you’re working with and their education opportunities?

Trauma just creeps into everything. Because [our kids] have been so busy, just trying to survive day to day, their trauma gets a little bit pushed back. But the minute they get stably housed, after about 30 days of being in the house, [they] start having these horrible flashbacks of all different things that have happened to them.

It can impact eating, it can impact sleeping — they just want to lay in bed all day. It can impact going to school, even being able to listen to their teacher. That’s usually the moment that we kick in the mental health specialists.

The other thing we see all the time is, because our kids are so angry — and rightfully so, people that should have protected them have let them down — they end up saying things to a teacher that they obviously shouldn’t say. And so they end up getting a [discipline] referral at school, and a lot of times end up being released for the day, when, really, they need help.

It’s so hard to point your finger at the schools and say: “You should be doing this or that,” because they’re doing the best they can with the resources that they have. I think they need more resources.

You try to strike the right balance between providing meaningful guidance and support, and also letting young people advocate for themselves and make their own choices. You write that a lot of times, unaccompanied homeless youth have learned to be incredibly resourceful and resilient, but they also lack basic skills, like cooking for themselves.

It’s hard. The way that I approach everything now — which is not how I did it previously — is that [I say]: I’m trying to look ahead for your future. [For example], every year we do an etiquette class. The majority of our kids have never been to a restaurant, they’ve never ordered off a menu. And we talk about: This isn’t about today. We’re not judging you. We don’t care that you don’t know. However, when you have your first interview over a meal, you’re going to be expected to know this.

It also comes down to: Is my help going to matter in that moment? Or should I back off, because it’s not dire right this second. I find that when I give the kids space, they’re more willing to listen. I let both of us just calm down, and then come back to it, and come up with a strategy that works.

In the book, some students say: There’s this white woman in front of me asking me personal questions, I don’t know if I trust her, I don’t want to be seen as a charity case. How have you learned to navigate some of the racial and socioeconomic divides between yourself and the kids?

I am who I am. I don’t think I try to change that divide.

There was a student in our program who said to me: “You’ll never understand me.” They’re in our program right now. And I said: “Well, try me, is there something going on?” [The student said]: “I can’t tell you, and you’ll never understand me.”

[Then one Saturday, the student called me] and she’s hysterically crying. And I find out that she’s so upset because her mother was investigated again by [Florida’s Department of Children and Families]. We probably were on the phone for an hour, just talking. By the time she hung up, she said to me: “Thank you for answering your phone.” And I said: “I’ll always answer my phone, that isn’t even a question. I’m here for you.”

And that changed everything. I do understand her now, in her eyes.

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.