Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

When thousands of Syrian families fleeing violence resettled in Canada several years ago, Ontario’s school mental health agency wanted to give schools tools to help refugee children process their traumatic journeys and adjust to their new lives.

The children didn’t necessarily need intensive support. But kids were bursting into tears and struggling to explain how they felt. Parents, too, noticed their usually social children had become more withdrawn and were struggling to make friends. That was especially common after kids had been in Canada for a few months and the honeymoon period ended.

So a team of experts in child mental health put their heads together and developed a program for newcomers that focuses on their strengths and who they can turn to for support. Known as STRONG, the program is now used across the U.S. in several cities serving lots of newcomers, including Chicago, Boston, Seattle, New York, Minneapolis, Washington, D.C., and Little Rock, Arkansas. Many others are asking for training, as schools struggle to meet the needs of students who’ve been through difficult journeys with limited school mental health staff, and even fewer bilingual ones.

STRONG, which stands for Supporting Transition Resilience of Newcomer Groups, can’t solve everything. Some kids may still need more intensive mental health support — and finding the time and staff to run these groups can be challenging. But many experts, educators, and students themselves see the intervention as a promising tool to help newcomers forge connections and head off mental health struggles before they turn into a crisis.

“They’ve just really appreciated the opportunity to connect with other kids,” said Lisa Baron, a psychologist who trains schools to use STRONG and directs the Boston-based Center for Trauma Care in Schools. “A lot of them said that they just had not really known that other kids were feeling the same way as they were.”

Why some newcomers struggle with mental health

Newcomer students can be refugees or asylum-seekers or the children of undocumented immigrants. Some arrive with families, some arrive alone. Some have been in the U.S. for just a few days or weeks, while others have been here longer. And while their experiences vary, they’ve often faced various hardships, from hunger to abuse.

Many children did not feel in control during their travels, and now crave stability and predictability.

It can also be difficult for newcomer families to access mental health services in the U.S. — driving home the importance of offering help at school. There’s often stigma around seeking treatment, and some families fear that doing so could put them at risk for deportation.

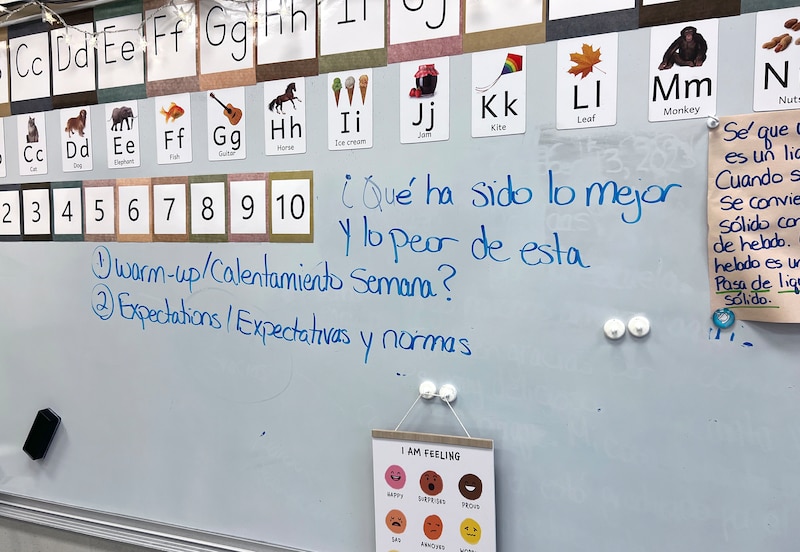

Here’s how STRONG typically works: The school identifies a group of students who are close in age and relatively new to the U.S. who could benefit from extra support. Then the school makes sure parents are on board, which can mean having careful conversations, especially if families are unfamiliar with schools offering mental health support.

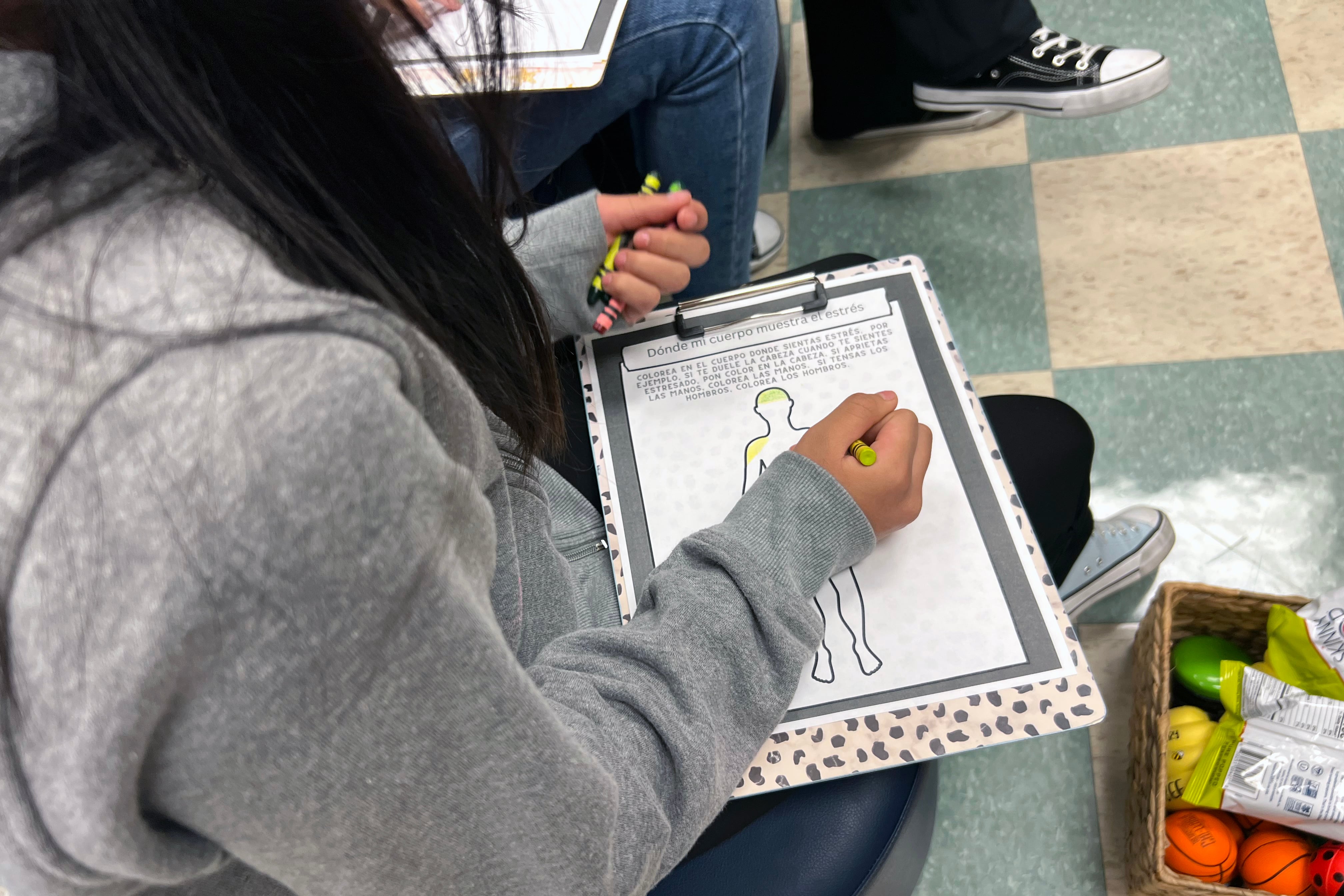

The group meets for 10 sessions, usually during the school day. Early sessions help students understand that it’s normal to feel overwhelmed or stressed sometimes. Kids learn different relaxation techniques, such as curling their toes into the floor as if they were standing in a mud puddle, or visualizing the sights and smells of a favorite place.

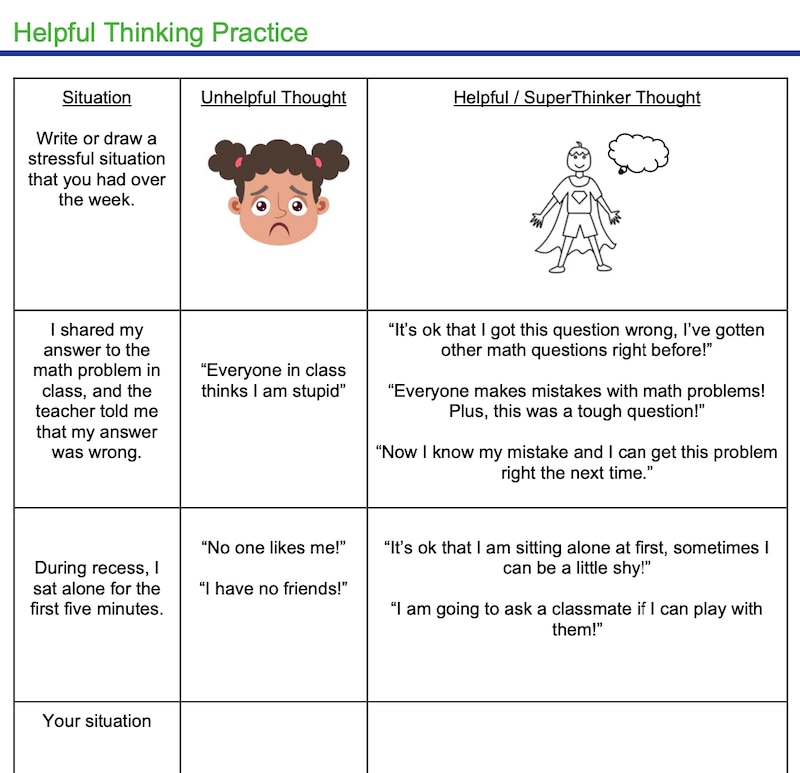

In later sessions, they learn coping and problem-solving skills, such as how to map out steps to achieve a goal. Kids who are shy about speaking English could identify people they’d feel safe practicing with.

“The coping skills [are] what will stay with you forever,” one Ontario student told Canadian researchers for a 2019 report. “Whenever you are in a stressful situation, you will always remember what to do.”

What makes STRONG unique and appealing to many schools, said Colleen Cicchetti, a pediatric psychologist who helped develop the intervention, is that it takes a strengths-based approach.

“There were strengths that were inside you that you had in your home country that are still with you, here, today — how do we build on them?” said Cicchetti, who directs the Center for Childhood Resilience at Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and now trains schools on how to use STRONG. “We really want young people and their parents to say: ‘This is a part of who I am and what I’ve experienced, but it shouldn’t define who I am entirely.’”

That’s what attracted the attention of mental health and school staff in the Madison, Wisconsin area. The district tried tweaking another group that addresses student trauma to help newcomers, but realized it wasn’t quite meeting their needs.

Kids need to “talk about good memories and coping strategies, not necessarily the exposure to the traumatic event,” said Carrie Klein, a school mental health coach for Madison Metro schools, which is considering using STRONG.

For Jennifer Moorhouse, a teacher who works with English learners at Brighton Park Elementary School in Chicago, STRONG has been transformative for her and her students.

Related: Amid Chicago’s migrant influx, one school is trying to help newcomer students navigate trauma

Over the last year, Moorhouse has run four STRONG groups — known as “clubs” at her school — alongside school counselor Stephanie Carrillo. The program helped Moorhouse get to know newcomers’ families, and has made students comfortable to seek her out when they need essentials like toothpaste or body wash.

The group has helped in unexpected ways, too. When kids said they weren’t eating at school because they didn’t like the food, Moorhouse figured out they did like Ritz crackers and Skinny popcorn, so she keeps those on hand. And when she found out some newcomers were crying in the bathroom, upset that they were going to miss their quinceñera back home, the group threw a big party at school, complete with balloons and empanadas.

“The students really have created this bond with Ms. Moorhouse — that’s their person,” said Cecilia Mendoza, the assistant principal. “Every student needs someone. For someone new entering the country, entering a new school, having someone is even more important.”

Brighton Park is one of 83 schools across the district that’s been trained in STRONG, with another 50 schools in line to be trained next school year.

Why talking about their journeys can help newcomers

When experts first developed STRONG, they imagined it would be delivered by social workers, school counselors and other mental health staff, since many newcomers have experienced trauma.

But given that mental health professionals are often stretched or in short supply, more schools are asking for others to be trained, too, said Sharon Hoover, a psychiatry professor at the University of Maryland’s School of Medicine who helped create STRONG.

Now, many schools run STRONG sessions with two adults. A teacher with language or cultural skills can act as the interpreter, while the staffer with mental health training takes on tasks such as screening children for post-traumatic stress.

“We don’t want to be irresponsible with the curriculum and just throw it into the hands of anybody who has no mental health training at all,” Hoover said. “But on the other hand, we don’t want to restrict it in a way that’s going to lead to it not getting to students who might benefit.”

On a recent Tuesday morning, Hoover and Bianca Ramos, a STRONG trainer, showed what a one-on-one session that invites students to share about their journey can look like during a virtual training for two dozen school staffers.

The group, mostly social workers and school counselors from Connecticut, had gathered to learn strategies to help newcomer students from many parts of the world, including Haiti, Guatemala, Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, and Ukraine.

Related: We are facing a migrant mental health crisis. More school social workers could help

In the video demonstration, Hoover sat beside Ramos in the corner of a blue-walled room. Ramos, a Chicago-based social worker, played the role of a 13-year-old girl who’d fled Guatemala without time to say goodbye to family and friends after her father was killed. Hoover explained that talking about something hard can be like stepping into cold water.

“The more we do it, slowly and gradually, usually the more comfortable we get,” Hoover said. “You don’t have to dive right in.”

In the scenario, as the young girl neared the U.S.-Mexico border, robbers threatened to take her family’s few belongings. Hoover asked how she got through that time, using it as an opportunity to draw out the child’s strengths.

“I had this picture of my mom and I just remember looking at it, and trying to stay hopeful that I was going to be able to see her again,” Ramos said. And she had her little sister to watch out for: “I was like a mom to her.”

“That’s amazing,” Hoover replied, pointing out how brave and caring the child had been.

Later, Hoover asked if the girl was having trouble sleeping, reliving any memories, or feeling sad a lot. She wasn’t, but thoughts of her dad did pop into her head in class, making it hard to concentrate. Hoover made sure that wasn’t happening too much, and then kept the door open to talk more in the future if anything changed.

In Chicago, Moorhouse has seen that some kids feel relieved when they share about their journey. But she also cautions that it can be a lot for other students and teachers to take in. After one student shared details that made Moorhouse tear up later, she realized she couldn’t probe too deeply in her conversations with the student, and needed to let the school counselor step in.

“We’re not therapists,” she said. “That’s very important for teachers to realize.”

STRONG can help students, but there are challenges

STRONG is still being rigorously evaluated in the U.S. But research conducted by Western University in Canada, where STRONG was first piloted during the 2017-18 school year, has shown promising results.

Evaluations from across Ontario found the program helped kids build trust, increase their confidence, and develop a sense of belonging at school. Students reported that STRONG helped them feel more welcome and connect with their peers.

STRONG can also shift school culture and help the entire staff become more attuned to newcomers’ needs. When Moorhouse notices certain patterns of behavior, she shares that with other teachers, so they can keep an eye out.

That could be explaining why some kids may not want to take off sweaters or jackets — after border agents took everything they had except for what they were wearing at the time — or that playing certain sounds, like chirping birds or rushing water, could be upsetting to kids whose journey involved swimming or walking through the jungle.

There can be practical challenges. School leaders may be hesitant to pull kids out of class for STRONG when they are struggling academically. Elizabeth Paquette, who’s part of the team that trains school staff in Ontario, said it can be tricky to get enough kids together in smaller schools and rural communities without resorting to virtual groups that can make it harder for students to make friends.

And if groups use more than two languages, the interpretation needs can take away from the group’s conversational flow.

Still, Moorhouse said the group can be a place for kids to talk about those academic struggles, whether they’re lost in class or frustrated because they already know the content, but can’t yet express themselves. This year, especially, kids want to talk about school stress even more than their journeys.

“They were struggling with: ‘Do I give up?’” Moorhouse said. And her message was: “Let’s keep finding other ways to work through this. What are your thoughts?”

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.