I have no vivid recollections of attending a segregated school, but I am aware that my educational journey commenced in Head Start at what was then Lincoln Consolidated School for Black students.

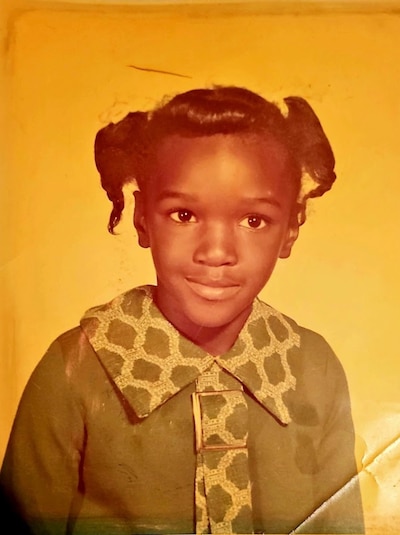

I was born in 1964 — my middle daughter playfully labels me a “Baby Boomer” — and my life aligns with my county’s momentous period of school desegregation.

My earliest educational memory is going to first grade at Happy Home School, a couple of miles from my home on the outskirts of Rockingham County, North Carolina. There, I was under the tutelage of Mrs. Neal and Mrs. Price, two impeccably dressed Black women. They were the only women I saw outside of church who dressed so elegantly. My journey continued with Mrs. Jones as my fourth grade teacher and Mrs. Townes as my fifth grade teacher.

Happy Home School only went through seventh grade. By that time, the county school system was in transition as new schools were being built. I had two Black teachers in eighth grade: sisters, Mrs. Jefferies, the English teacher — to this day, I think about her whenever I see a diagrammed sentence — and Mrs. Blackwell, the math teacher. At the new county high school I attended, I had a couple of Black teachers, too: Ms. Lindsey for English and Mrs. Keesee for business.

Recent scholarship tells us that Black students with one Black teacher by third grade are 7% more likely to graduate high school and 13% more likely to enroll in college. After having two Black teachers, Black students’ likelihood of enrolling in college increased by 32%. Growing up, I knew nothing of this. I was a student whose parents never graduated from high school in rural North Carolina, who loved to read, and who decided in seventh grade that I would be a lawyer.

May 17 marks 70 years since the landmark Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which found racial segregation in schools to be unconstitutional. I cannot personally speak to what it’s like to attend a segregated school. I can, however, speak to the power of Black teachers, many of whom were forced out of the classroom following the decision.

Speaking over the years to those who did go through a segregated school system, not once did I ever hear sorrow, neglect, or regret. I have heard stories of pride, responsibility, and community and what was lost when Black educators were pushed out when Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision dismantled the Black educational community.

I would come to understand that Black educators, even those who were more highly qualified and degreed than their counterparts, lost their teaching positions. The roles they had long filled went to white teachers amid school desegregation efforts. Some 38,000 Black teachers were displaced in the South alone in the decade following the Brown decision, research has shown.

In some cases, racist educators refused to hire Black teachers. In others, they were demoted for no good reason, or forced to sit for new licensing exams that, according to Leslie T. Fenwick, the author of “Jim Crow’s Pink Slip,” served a “racist agenda.”

The loss of Black teachers, especially Black males — I would not have a Black male instructor until my senior year of college — has been chronicled in books such as Fenwick’s and “Greater than Equal” by Sarah Caroline Thuesen. This mass displacement had profound effects on communities and the teaching profession, ravaging the Black teacher pipeline for decades to come. The fallout explains why Black teachers are so often underrepresented to this day, Fenwick has said.

Knowing what I know now, I wonder if the outcome would have been different for me if I had not had those Black teachers sprinkled among the exceptional educators who taught me through high school. I know that my opportunity to graduate from college plotted the course for my daughters to do so, which they did.

More than four decades after I graduated high school, I think about how many students in the district I attended — the same district where I now work — may go through the whole K-12 system without ever having a Black teacher. I teach at a high school, and for most of my students, I am the first teacher of color they have ever had, and I don’t get them until their sophomore year.

So 70 years after the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the words of the legendary Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes resonate still:

The past has been a mint

Of Blood and sorrow

That must not be

True of Tomorrow

Valencia Ann Abbott is a social studies and history teacher at Rockingham Early College High School in Wentworth, North Carolina, where she was named the school’s 2024-2025 Teacher of the Year. Abbott received the 2024 Civil Rights/Civil Liberties Excellence in Teaching Award from the North Carolina Council for the Social Studies in partnership with the Social Studies School Service.