Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

To unearth the forgotten history of the Kansas women who served as plaintiffs in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case, Donna Rae Pearson had to dig.

Without published scholarship to go on, Pearson and two other researchers hunted down the women’s obituaries, cross-referenced their details against Census records and city directories, and pored over newspaper clippings, oral histories, and court transcripts.

It was no easy feat: Some women’s names had changed, and some had moved as far away as Oregon.

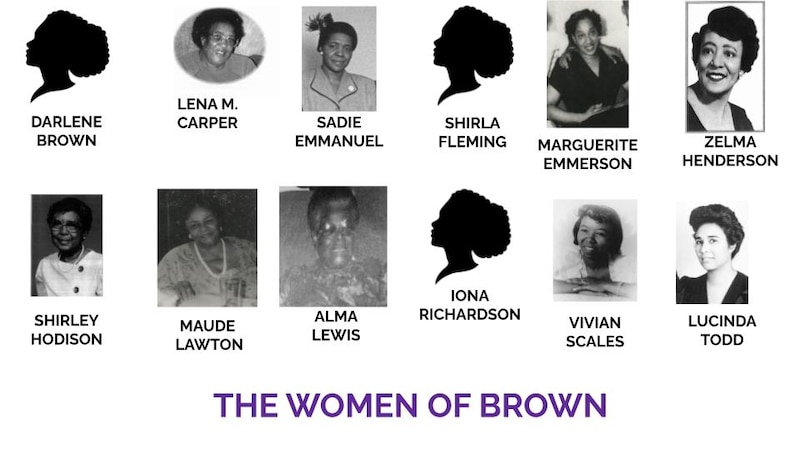

The result of their work is “The Women of Brown,” which recognizes the lives and contributions of the 12 Black mothers who signed their names, alongside Oliver Brown, to the lawsuit that reached the Supreme Court.

A pop-up exhibit showcasing their findings is traveling across Kansas to mark the 70-year anniversary of the landmark decision. That includes a stop at Topeka Public Schools’ commemorative event this week.

Pearson hopes that students and others who see the exhibit will leave curious to find out more about the Black women who committed acts of “everyday activism” to further their children’s education.

“I don’t think Black women — I don’t think women — get the credit that they are supposed to have when it comes to these kinds of activities,” said Pearson, a museum curator at the Kansas Historical Society and a former local history librarian at the Topeka & Shawnee County Public Library. “I think that’s becoming more and more of a conversation that we have today: How did they contribute to these movements?”

The documents Pearson and her team collected will be housed at the Kansas Historical Society State Archives and Topeka’s local library, so future researchers won’t have to do as much legwork. Pearson is also starting to hear from relatives and others who knew the women, which she hopes will contribute to the scholarship, too.

“We just needed to bring them out of the dark,” she said. “We needed to say their names out loud again.”

Chalkbeat spoke with Pearson about why the 12 women joined the lawsuit and the challenges of researching Black women’s history. She also has thoughts on how students and teachers can keep the conversation going (see sidebar).

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

How did the 12 Black women who became plaintiffs in the Brown case come to be part of the lawsuit?

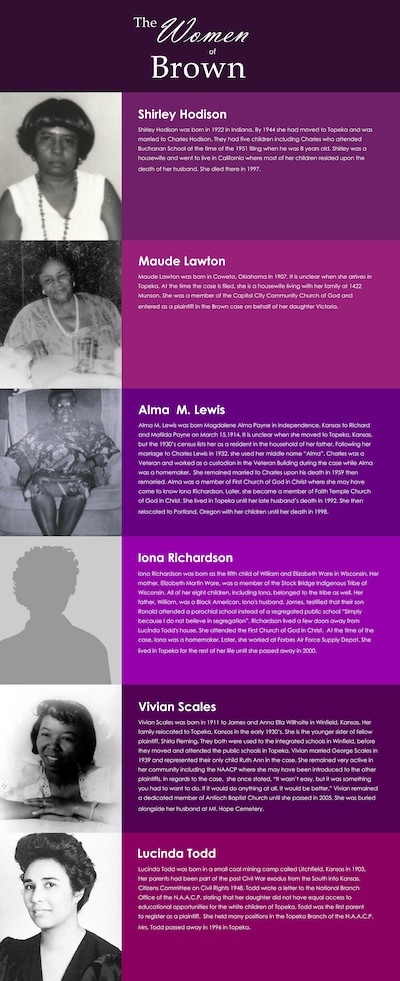

We don’t know exactly how all of them came to be part of it. Lucinda Todd, one of the plaintiffs, and actually the first plaintiff to sign up, was heavily involved in the NAACP. She was on a special committee when talk of this lawsuit started happening, and she helped recruit parents.

We also identified different locations throughout the city [of Topeka] where these women could have possibly met. They were all involved in formal religious activities. Some of them went to church together. Some of them were involved in social clubs together. So we believe there was this network where they could have been simply having coffee or tea and saying: ‘Hey, I decided to sign up. How about you?’

Why have they historically gotten less attention than Oliver Brown?

In our legal system, ‘et al’ can hide a lot of things. That means ‘and more.’ Et al really covers up, initially, the fact that these women were part of the case.

But then you go into a little bit deeper reasons. These are Black women. And our history is not recorded as well as the majority’s history.

The case, initially, was not necessarily as well-received, for different reasons. Why this case happened does not fit our prevailing narrative [in Kansas] of being a ‘free state,’ a state about civil rights. We were actually one of three northern states that allowed permissive segregation, which means, by law, they could segregate.

What were the ways in which the women saw that their children were not getting equal opportunities as white children at school?

When you read the transcript from the local court trial, you’ll find that there were problems with the busing system and being able to pick up their children in a timely manner. The Brown children had to walk almost a mile by railroad tracks just to get to their bus stop. These long commutes would have interfered with their schooling. You’re going to get up earlier than a person who’s going to walk two minutes. That’s eating time before school and after school.

[Students who lived far from their schools] couldn’t go home for lunch. They had to bring lunch, and supposedly the lunch wasn’t going to be as nutritious as a hot, home-cooked meal.

There were other things, in terms of activities that were not available. What sparked some of this was Lucinda Todd was super mad about the fact that her daughter, Nancy, could not participate in the district-wide [music] program. There were 18 schools, but only 14 of them were participating. What schools did they leave out? The four Black schools. It was because of Lucinda Todd’s complaints that they were finally able to get [music programs].

There were sports available at the upper levels in Topeka, but the [activities were] segregated. So there was a Black basketball team and a white basketball team. There was a Black prom and a white prom. Even though they all went to school together, all those activities were actually segregated. [Kansas law at the time permitted segregated elementary schools, but high schools were supposed to be integrated.]

Initially, the women were featured in some news coverage, but then their voices just kind of dropped out. What were you able to glean from what they did share over the years?

As the secretary of the NAACP, Lucinda Todd sent out this very long press release that explains the case to the community. But over time, you see the male figures that were involved with the case, they continue to be elevated. But the women, you don’t see them asked as many questions later on, or any questions.

Toward the ‘80s and ‘90s, when the historic site was being lobbied for and built here, they brought them back again. Locally, the one disarming piece that I found was an article that was talking about them, and it tried to give a status update. It kept saying: ‘No information known.’ And we discovered that some of these women were actually still alive, living in the city.

But I also have to remember … the challenge with doing women’s history — not just Black women, but women in general — is we are [often] forced to change our names. In some cases, especially then, they were not referred to by their first and last name. They’re referred to as ‘Mrs. Brown.’ And it’s like: ‘Well, Mrs. Brown surely has a first name!’ So that made it a little bit challenging.

How do the women who participated in this lawsuit fit within the larger tradition of African American women participating in advocacy and organizing in their communities?

It’s kind of a culmination of all the experiences they were able to have. Colored women’s clubs were here as early as the 1890s. Black women are the backbone of those [church] organizations. When you decide to have an event at church, and you’re the one in charge, you start organizing. You start getting people on board, you start raising money.

We had Black women who were involved in entrepreneurship. There were women who owned their own businesses. They were not used to necessarily sitting on the sidelines here. I think as organizers, they were in a community where it was acceptable for them to sign up and do things like this.

What lessons can we draw from ‘The Women of Brown’ about the significance of everyday activism?

I think we need to broaden our definition of what activism is. It is not always Martin Luther King, standing at a pulpit. Everyday activism is really the little things that you can do in your own community to make a difference. It’s when we take a stand for something that we believe in.

Some would say what I’m doing right now is being an activist. I’m bringing up a story; I’m posing challenging questions.

Did you make any personal connections to what you learned about the women of Brown?

As a historian, I very intentionally did not talk about the decision [in the past]. Part of the reason was because of the way it is portrayed in the media. Yes, it is a celebration of sorts. But y’all have to remember, the reason why this case happened is because there was blatant segregation in this state for an extended period of time, within our lives.

My class, when I entered elementary school in the ‘70s, was considered the first truly integrated class. My older brothers, my older sisters, in particular, went to segregated Black schools. And this was post the [Brown] decision. These are things we are still wrestling with.

I didn’t think we were looking at [the Brown decision] from a very truthful perspective. I don’t think we were looking at all the nuances, and the impact that it created on different communities.

During this time period, you had a couple of things happen to the Black community. Redlining forced us into one community. With desegregation of schools, you were breaking up that school network, that bonding of a community. Then the next step was urban renewal — that totally wiped out some of these communities.

I needed to look closer at the decision from another perspective, so I could understand it.

What would you like for students who are going to see the exhibit to take away from it?

I hope it’s a conversation-starter for them. I hope that they can relate to the women.

They were ignored. Hopefully, this will again bring them to the forefront and shine some light on them. Hopefully, it makes you curious enough to want to learn a little bit more about them.

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.