This story was published in partnership with The Trace, a nonprofit newsroom covering gun violence in America. Sign up for its newsletters here.

On Nov. 7, as school was getting out for the day, one teenager shot another across from Morristown-Hamblen West High School in Morristown, Tennessee, an Appalachian town of 31,000 people. As a precaution, the school was placed on lockdown, as were other schools and childcare facilities in the area.

Police said the 17-year-old suspected in the shooting allegedly stole a gun out of a parked car the day before. Both suspect and victim, also 17, were students in the county school system. But “the shooting did not take place on school property,” a local news report emphasized.

The high school, and another high school across town, saw a combined half a dozen school-adjacent shootings between 2014 and 2023, according to a Trace analysis of a decade of data from the Gun Violence Archive. That means lockdowns, crime scene tape, pockmarked walls, and a pervasive sense of dread.

Morristown is not unique. In thousands of communities across America, children are traumatized in their classrooms — not from bullets fired within, but from violence happening outside school walls.

Shootings like the one in Tennessee have become disturbingly common for American K-12 students. Between 2014 and 2023, there were at least 188,080 shootings within 500 yards of a school.

That averages to 57 shootings a day occurring near a school in the United States.

The Trace looked specifically at GVA data for shootings that took place within 500 yards of all public and private K-12 schools identified by the National Center for Education Statistics — more than 148,000 public and private schools.

Last year alone, more than 6 million children attended a school that had at least one shooting in this vicinity.

National attention is understandably focused on shootings that happen on school grounds during school hours. Less attention is paid to shootings around schools, which can also instill trauma. Schools are part of a community, and when a community is plagued by violence, students bring that burden with them to class.

Research has shown that childhood exposure to violence can have lasting effects on psychological and academic development. Early exposure to community gun violence can disrupt academic engagement, and hinder development of areas of the brain instrumental in decision-making, reasoning, and self-regulation.

But the trauma doesn’t have to be experienced firsthand in order to have a detrimental impact: In one study, neighborhood violence — measured in blood spatter and shell casings, police tape, memorials, and people fighting in the street — was associated with decreased reading proficiency on standardized tests for elementary schoolchildren.

Debra Furr-Holden, an epidemiology professor and dean of New York University’s School of Global Public Health, has studied the effect of gun violence on learning among children in high-crime communities in Baltimore for nearly two decades. On the walk to and from school, Baltimore city kids “are constantly exposed to the evidence of violence in their community,” she said. “You will see memorials on stop signs and light posts where somebody was killed. It’ll be like 20 teddy bears, a candle, a picture of the person.”

This exposure to violence takes a toll on concentration and emotional processing, and the deficits can follow kids through their academic careers and into adulthood, Furr-Holden said. “Their bodies may be in the room, but their minds are elsewhere,” she said. “All of this erodes attention and has an impact on learning, and it erodes a feeling of safety and security.”

Some schools are under siege

Our analysis identified 266 schools that had more than 100 shootings nearby, and they were largely concentrated in cities like Chicago, Philadelphia, and Baltimore that have well-documented gun violence struggles.

A radius of 500 yards around a school — about four blocks in a typical city — is also the range in which a child would be able to clearly hear a gunshot. At 500 yards, a gunshot can be in the 140-decibel range, the same loudness as a firework or a jet engine taking off, and louder than a chainsaw.

In Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, Russell Conwell Middle School and Frances E. Willard Elementary sit side by side. Nearly 500 shootings occurred in the area over 10 years.

On average, that is almost a shooting a week.

In 2022, three people were shot on Willard’s school grounds. Police found dozens of shell casings outside the school building. Last year, school staffers put bulletproof blankets in the windows, after an incident in which someone fired into the building during school hours.

Katoura Jones, 12, a sixth grader at Conwell, said that she often hears shots fired during the school day, and that it triggers her anxiety. “Sometimes when I’m in my tutoring class I hear gunshots going off, and I’m the closest one to the window because that’s where I sit,” she said. “They tell us to get down, but that’s when all we hear is screaming and yelling. That happens pretty often.”

Related: This Philly school had more shootings near it in the last decade than any other nationwide

The walk to school in neighborhoods that see high levels of gun violence overtakes children through blighted and disinvested areas, sending another harmful message. “They’re just being inundated with all these signs and signals that no one cares,” said Furr-Holden, the NYU professor. “It’s just like ‘I gotta be on my toes, I gotta make sure I’m tough enough that nobody tries to mess with me.’”

Children exposed to violence in their communities, Furr-Holden said, often develop coping mechanisms and then are unfairly stigmatized. Living amid violence “increases people’s vigilance, and we label them as ‘aggressive,’” she said, when in reality, they’re having a natural response to intense stressors.

“They don’t even realize that the majority of the world isn’t living under the same circumstances that they’re living under because it’s all they know,” she said.

Schools in Philadelphia do their best to keep kids safe. At Conwell, no parents are allowed in the building, for example. Instead, staffers bring kids outside when classes are over. But schools can only do so much.

The City of Philadelphia, which is home to 46 schools that had more than 100 nearby shootings over the last decade, offers a $10,000 reward for information leading to the arrest of suspects in shootings near schools and recreation centers.

In June, the Philadelphia Police Department announced that it was deploying 75 additional officers to Kensington and surrounding areas. The move is part of the city’s larger public safety initiative, and according to Deputy Police Commissioner Pedro Rosario, the department sought input from community stakeholders before the deployment. “We don’t take this process lightly,” said Rosario, a 29-year department veteran who was promoted in January specifically to focus on the area. “We really have to bring a sense of normalcy back.”

Related: Schools make a difference for students exposed to violence, new report shows

In Chicago, our analysis found, there were 97 schools with at least 100 shootings over the last decade.

In January 2024, Mayor Brandon Johnson held a press conference after three teenagers were shot outside Nicholas Senn High School just as classes were letting out. It was the second fatal shooting outside a local high school that week.

When asked how parents should feel about children’s safety at school, he focused on the city’s efforts to apprehend the shooters.

“My children will be in school tomorrow,” Johnson said. “And children across the city will be in schools tomorrow. Then we’re gonna do everything in our power to make sure that our young people are safe. But we’re also going to make sure that we bring these individuals to justice. We’re also going to make sure that we get at the root cause.”

Shootings near schools not just a city problem

Although schools in cities have more than their share of nearby shootings, nowhere is immune.

There were 44,812 school-adjacent shootings in cities with populations under 250,000: 30,913 in suburbs, 8,939 in small towns, and 4,131 in rural areas, according to a classification of school locations developed by the National Center for Education Statistics.

In October of 2023, a football game at Oxon Hill High School in Alexandria, Virginia, was postponed and the school was locked down after multiple shots were fired. The lockdown ended when police found a man shot to death in his car.

Even in the tiny, remote village of Chevak, Alaska, a man shot a village police officer and then himself in 2016, all within sight and earshot of a school playground.

Race is a factor in school-adjacent shootings

While students of all races experience the harmful effects of gun violence near their schools, the burden falls disproportionately on students of color, who are already more vulnerable and have fewer resources than their white counterparts.

During the 2022-2023 school year, one in 20 white students experienced at least one shooting near school, but one in four African American students did, as did one in seven Hispanic students, one in 11 Asian students and one in 12 Native American students.

In many communities, the pattern of exposure also mirrors residential segregation: Shootings are clustered around schools in the parts of town where Black and brown people live.

There is a clear racial divide running through Washington, D.C. The vast majority of the population living west of busy 16th Street NW is white. East of the same street, the population is majority African American.

Nearly all of the school-adjacent shootings identified by The Trace were on the eastern side of the district.

In May, a bullet came through a window at D.C.’s Dunbar High School, according to police, and grazed a 17-year-old student’s head. The school was placed on lockdown while police investigated. Over the last decade, there have been 132 shootings adjacent to the school.

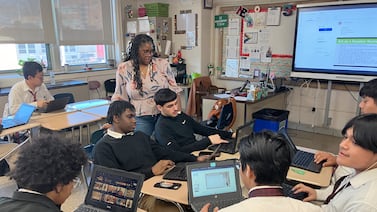

Sari Beth Rosenberg has taught history at the High School for Environmental Studies in Manhattan for the last 20 years and, in 2021, co-founded Teachers Unify to End Gun Violence.

The following year, a shooting on the New York City subway left 10 people wounded. A few weeks later, there was a shooting at a supermarket in Buffalo, New York, that left 10 people dead. Both incidents rattled her students because of their proximity, Rosenberg said. “I remember one kid saying, ‘This is starting to feel more close to home.’”

Schools need more federal funding for mental health professionals in schools, Rosenberg said: “We need to admit to the fact that kids are strapped with so much to process, and whether we want it to be or not, it’s happening at school.”