“Teachers, the school is currently in lockdown,” our assistant principal said over the loud speaker. “Please lock your doors and close your windows. This is not a drill. I repeat, this is not a drill.”

It was early in the day, first period. My AP Biology teacher turned off the lights and locked the classroom doors and windows. What I remember most about that day, back in 10th grade, was not the swift actions of the teachers, but the behavior of my fellow students. All of the roughly 1,400 students at Reseda High School in Los Angeles feared what this meant: a school shooter.

We spent the first 10 minutes of lockdown in complete silence, stealing glances at the classmates who might have been the last people we would ever talk to. We spent the next two hours playing video games on our phones and computers and searching for updates on the situation with the gunman.

Turns out, the threat was in the neighborhood, not the school, but we were all terrified.

About a year later, we were in lockdown again. I was a junior now, sitting on the bleachers. I am on the varsity soccer team and was waiting for our game to start when people around me started screaming and running. As I rushed to alert some younger kids who were sitting near me, I heard the coach yelling — not with the tone of someone trying to make an athlete better. He sounded more like a parent, urging their child to run from danger.

Being outside, we all sprinted to the nearest building. Once inside, we spent the next two hours listening to the police radio, hoping for an update. I never found out the school was placed on lockdown that December day. But once more, we were forced to wonder if we were taking our last breaths.

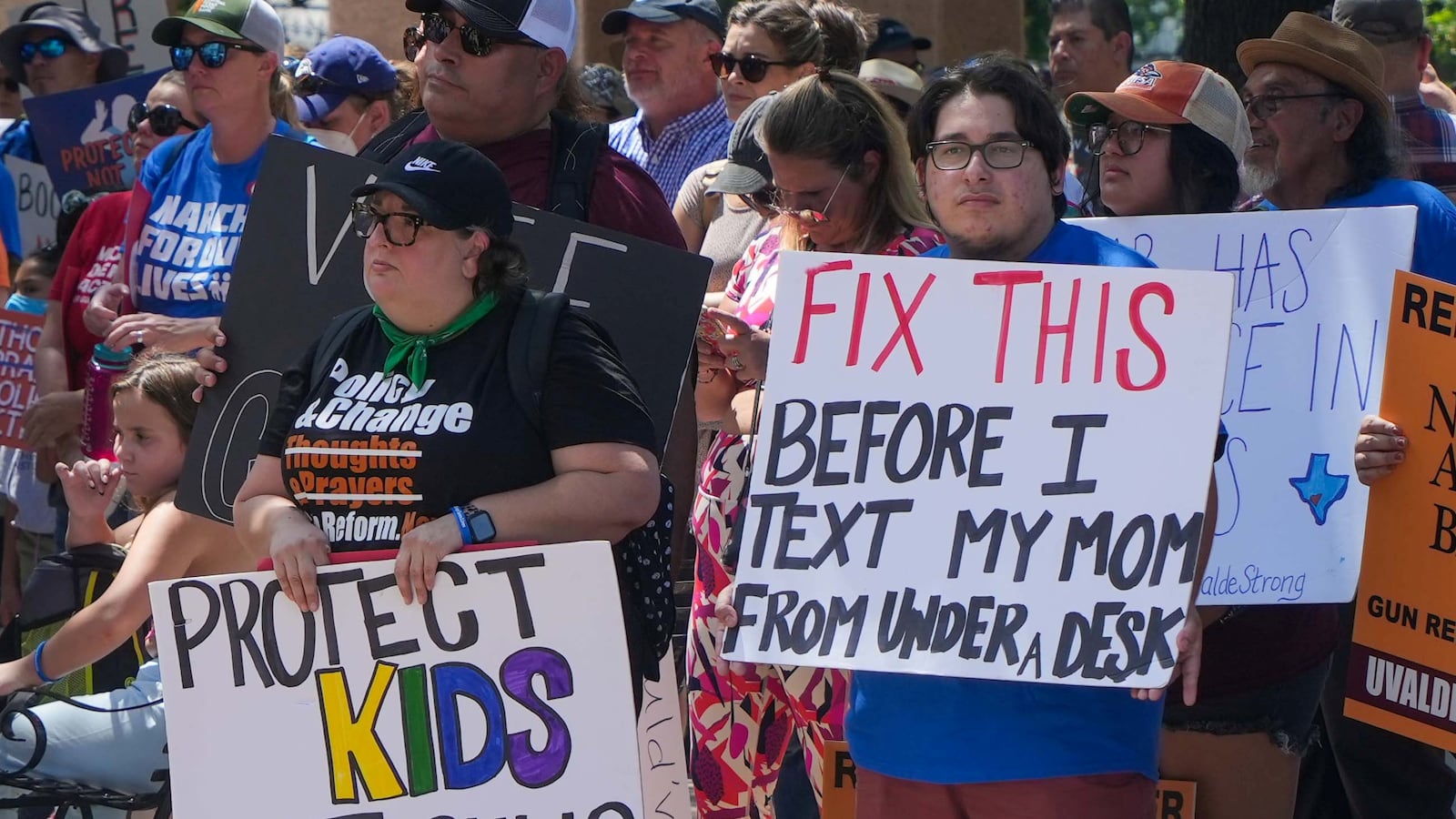

We all were well within our right to assume the worst, having lived through mass shooting after mass shooting, including deadly school massacres like those in Parkland, Florida, and Uvalde, Texas. As of this past weekend, when we witnessed a horrific display of deadly political violence aimed at former President Trump, there had been nearly 300 mass shootings in America this year.

About seven children in the U.S. lose their lives at the end of a gun barrel per day, making guns the nation’s No. 1 cause of death for children and teens.

My two experiences with lockdown are memorable, but I’ve also had four or five other conversations with my best friend about whether we were going to school the next day because someone had threatened to bring a gun. In addition, there have been repeated school shooter threats written on the bathroom walls. That means there are often security guards in front of the bathrooms, and those same bathrooms are locked as soon as the school day ends.

American students live in constant fear of gun violence, in schools and neighborhoods. The threat affects everyone, but especially still-developing young people like my classmates and me.

So many people — from teens who have survived school shootings to parents who have lost children to gun violence — have advocated tirelessly for common-sense gun control, like stricter regulations on buying and storing weapons. But the politics of it all means that little ever seems to change.

Somehow, we’re just supposed to accept that getting to and from school means risking gun violence, that sitting in class or on the bleachers means that at any moment, we could be in lockdown, quietly wondering if we’ve spoken our last words. We shouldn’t have to live in fear like this.

Neel J. Thakkar is a rising senior at Reseda Charter High School in Los Angeles.