Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

Millions of children in six states won’t get federally backed summer food benefits they’re eligible for until just before school starts. And in Delaware, Montana, and Nevada, half a million kids won’t get them until the new school year begins.

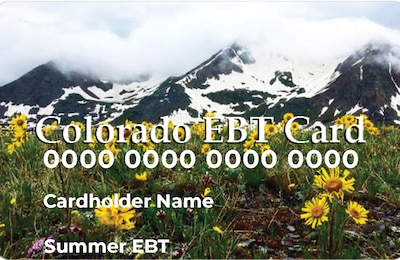

Summer EBT, also known as SUN Bucks, provides low-income families with $120 per school-age child to buy groceries over the summer. It’s a rare example of a pandemic-era program that Congress made permanent, and most states are offering it for the first time this year.

But delays and start-up challenges have dogged the program. Some states have identified hundreds of thousands more children who are eligible for Summer EBT than they initially expected. That’s underscored the widespread need for food assistance and will bolster the program’s impact. But it’s also complicated getting the program off the ground. Such problems have left families who were initially told the aid would arrive sooner scrambling to make ends meet.

Many states and schools did so little to publicize Summer EBT that families have no idea when or how their benefits will arrive.

“This hurts families who were counting on the benefit to be deposited by a certain date, and now they have to wait several weeks or months,” said Kelsey Boone, who’s monitoring the Summer EBT rollout for the nonprofit Food Research & Action Center.

Still, many states did manage to get their programs up and running on time. Officials there say the aid that’s reached families is making a difference, especially at a time when food prices remain high. Families will have four months to spend the benefits, even if it arrives late.

There’s been “a very massive response to this program,” Boone said. “It really just shows how much this program is needed by so many families.”

Felina Romero’s three kids eat breakfast and lunch for free at school. But during the summer, her food benefits often run out mid-month. The cereal and juice she gets from food pantries often last just a few days.

The Colorado mom had planned to use Summer EBT to buy bottled water and snacks to help her kids stay full.

But after weeks of calls to her state’s helpline — “It’s delayed, it’s delayed,” she kept hearing — Romero recently found out that families may not get their benefits until August, when many schools are back in session.

“If they would have gave us that during the summer,” she said, “it would have helped us so much.”

Summer EBT has roots in pandemic aid

Anti-hunger advocates have long considered summer one of the toughest times to reach children.

Many schools serve free summer meals. But parents often struggle to get to them, either because they’re far away or open only during work hours. Families who rely on food banks say they often can’t find staples their kids need, like milk. And often, the food is nearly expired.

Summer EBT allows families to shop for themselves — part of a pandemic-era trend to provide families with more direct aid.

“Only parents and families know what’s best for themselves and their children — what they’re actually going to eat, what they’re capable of eating,” said Hope Lane-Gavin, who directs nutrition policy and programs for the Ohio Association of Foodbanks, which is helping get the word out about Summer EBT. “Most food pantries can’t really tailor a box to a gluten-free kid.”

Pandemic EBT, which launched when schools were closed, helped lay the groundwork. States found that families liked that program, and it helped agencies set up new systems they’re now tweaking for Summer EBT.

Thirty-seven states signed up to run Summer EBT this year, while the other 13 opted out. Some Republican governors objected to providing families with more government assistance. Other states said they didn’t have the funds or capacity to stand up a new program in a few months’ time.

Why Summer EBT benefits are arriving late

States that chose to participate were supposed to start distributing benefits around the time that most schools let out for summer break. But many states reported a number of complications that led to benefits not going out on time.

In Montana, a third-party contractor backed out at the last minute. In Nevada, the legislature didn’t approve funding for administrative costs until June. In Pennsylvania and Illinois, officials said it took time to develop new systems, and benefits will go out earlier next year.

Colorado had to hire a new team and identify kids who automatically qualified for Summer EBT through their participation in other programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and the free and reduced-price school meal program.

Colorado ended up identifying 550,000 children who qualified for Summer EBT — a whopping 190,000 more than the state initially estimated.

It was a “very happy problem,” said Laura Kriebel, who’s overseeing the program for the Colorado Office of Economic Security, but also a “pretty big lift.”

For example, the state had to work with schools to get up-to-date mailing addresses and run data checks to make sure it didn’t mail out duplicate benefits.

It also had to set up an application process for families who didn’t automatically qualify through other programs. That represented a big change from Pandemic EBT, which had no application.

The state started sending out letters to let families know if they were eligible last week. Benefit cards could arrive later this month. But families may not get them until later in August, when many students are already back in school.

“I realize how tough it is to get the question mark from Colorado of: Where are my benefits?” Kriebel said. “But we are just trying to be thoughtful about this since this first program year does have a lot of challenges with getting the benefits out the door accurately.”

How some states rolled out Summer EBT smoothly

North Carolina is one of around a dozen states that successfully distributed benefits earlier in the summer. The state identified an additional 266,000 eligible children, but still got benefits out in mid-June.

Madhu Vulimiri, a deputy director at the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, attributes the state’s ability to stick to its timeline to the “constant communication” between the state and its benefits issuer. Communication breakdowns contributed to delays elsewhere.

Relationships built through Pandemic EBT with North Carolina’s education agency and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians helped get student data to Health and Human Services quickly.

And crucially, North Carolina took the extra step of identifying families that would likely qualify but needed to fill out paperwork. Then the state sent them invitations to apply via text, email, and phone in June — something other states did not do.

“We’ve been seeing a good response to that,” Vulimiri said. “Given that it’s the first year, we wanted to make sure we got the word out and tried to minimize the chance that we might miss somebody.”

In Arizona, early planning helped the state get benefits to families that automatically qualified through SNAP or another program in early June. For kids that needed a new card, the state also decided to group benefits by family unit, which sped up mailing times.

“If you wait too long, before you know it, the summer is here and no one is committed to doing the program,” said Ernest Baca, a deputy administrator in Arizona’s Department of Economic Security.

One big goal now is to make sure families know they have only 122 days to spend Summer EBT benefits once they receive them — a shorter timeline than other forms of food aid.

That’s especially important after hundreds of millions of dollars in Pandemic EBT aid expired without being spent, according to data compiled by education consultant David Rubel. Often that was because families never got their cards, or had trouble using them.

To head that off, Colorado set up a system to see which families have yet to spend their aid and will send out reminders before Summer EBT expires, Kriebel said.

Going forward, officials across the country say their states plan to issue benefits earlier. The U.S. Department of Agriculture recently announced it would award $100 million in grants to help states and tribal nations make updates to their technology systems to run Summer EBT more smoothly.

Families still waiting for their benefits say they hope states can do better in the future.

That includes Stephanie Hall in New Mexico. Her state isn’t planning to send out Summer EBT benefits until early August — just before most New Mexico kids go back to school. The aid would have been especially useful for buying snacks for her 15-year-old daughter, who is pre-diabetic and needs to eat every few hours to regulate her blood sugar levels.

“I’m actually fighting to sustain my family,” Hall said. “They let us down.”

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.