This story is published in partnership with The Hechinger Report. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

It’s a Sunday in June, and high school history teacher Chris Dier is poring over readings, lesson plans, and other resources to put together next year’s curriculum for his Advanced Placement U.S. and World History classes.

School doesn’t start until mid-August. But Dier, Louisiana’s teacher of the year in 2020, has followed this same routine for years. He spends part of his Sundays throughout the school year and summer preparing lessons for his classes. In his 14 years of teaching, Dier said he has never really had a curriculum provided by his school district that he can use without making significant adaptations. In fall 2020, he started teaching at Benjamin Franklin High School, in New Orleans, a top-performing charter school that doesn’t offer teachers any curriculum or materials.

“For better or worse, essentially, we are responsible for creating our own curriculum,” Dier said. “The curriculum I teach is purely something that I create.”

Every year, school districts across the country spend millions of dollars on curriculums, the planned sequences of materials teachers use to guide instruction. Many buy off-the-shelf materials created by curriculum companies, while a few districts create their own.

But many teachers say those materials don’t always work well — at least not without changes. Teachers say curriculums aren’t culturally relevant or inclusive, don’t prioritize a student’s perspective, ability, and experience, and seem to be created by providers who are removed from the classroom. In some cases, teachers say a lack of professional development on how to implement a curriculum can make it hard to use.

It’s long been common for teachers to write lesson plans and adapt instruction to their students, to a degree. Some districts and schools, like Benjamin Franklin, where Dier teaches, even expect it, asking educators to create their own curriculum using state standards and subject-specific frameworks from groups like the College Board as a guide.

But teachers, regardless of where they teach, say that they often spend a significant amount of time and effort creating and refining curriculum materials. Experts and researchers warn that if teachers are provided with a high-quality district curriculum and mix it with materials from sites like Teachers Pay Teachers and Pinterest, which some experts say have low-quality, unvetted resources, they dilute otherwise rigorous content, and create inequities among students.

David Steiner, executive director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy, said he thinks curriculum providers need to do a better job of offering curriculums for students who have genuine challenges with grade-level materials and for English language learners. Steiner’s team at the institute surveys teachers nationally to determine what curriculum they use in the classroom, and how they use it. Based on some of those responses, Steiner said he worries that there’s also a “sort of resistance to a scripted curriculum” among teachers who say it doesn’t properly build on or connect to a student’s prior knowledge or experiences.

“The research is against them,” Steiner said. “The research is heavily in favor of following a script — not necessarily every last letter of that script, but following a really good curriculum that’s standards-based and content-rich.”

States push for higher quality, standards-aligned curriculums

A curriculum is meant to guide educators in what to teach students in particular subjects and grade levels, and should be aligned with a state’s standards on what knowledge and skills students need. How a curriculum is designed, rolled out, and used in the classroom varies by state, district, and teacher.

Steiner, who has worked with several states to implement high-quality curriculum, said there has long been a tradition of school districts and state education leaders recommending, but not mandating, a particular curriculum. That creates a risk that inexperienced teachers might select materials that are below grade-level, according to Steiner, who referenced a recent report on the subject from the education nonprofit TNTP.

There have been attempts to better align curriculum to learning standards. In 2017, the Council of Chief State School Officers created a network designed to help states implement high-quality, standards-aligned curriculums. At least 13 states, including Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Texas, have signed on since then and have begun developing initiatives to review curriculum to ensure it is high quality and to help districts use vetted materials.

Louisiana has also served as a model of how to better align curriculum with state standards and provide teachers professional development, according to a 2019 survey by the group RAND. Louisiana’s use of standards-aligned materials was higher than other states, with 71% of math teachers in Louisiana and 80% of English language arts teachers reporting they used such materials and understood what their subject standards are. (The next-highest state for math was Delaware, where 51% of teachers of that subject reported using standards-aligned materials.)

Related: How a Colorado district changed its reading curriculum to better reflect students

Alexandra Walsh, chief product officer at curriculum company Amplify, said that ultimately “it is the district’s responsibility” to determine how a curriculum is used. “We really try to put great materials in the hands of teachers and let them make informed and great decisions about what to do for their students,” she said. All of Amplify’s curriculums include pacing guides, she added, so if a teacher needs to modify a lesson, there is room to do so. The company also tries to provide at least one day of professional development on each curriculum.

Julia Kaufman, a senior policy researcher at RAND and a co-author of the RAND report, said a high-quality curriculum should be standards-aligned, have built-in support and instructions for teachers, engage students in a meaningful way, and include assessments that are tied to what a student is being taught.

According to the survey and other research by Kaufman and her team, elementary and high school ELA and science teachers are the most likely to cobble together materials from several different comprehensive curriculums. Math teachers are more likely to be what Kaufman’s research identified as “modifiers,” who make considerable changes to a single curriculum or supplement it to better address students’ needs. Only 19% of teachers surveyed were “DIY teachers,” meaning they use a completely self-created curriculum. DIY teachers also tend to be high school teachers of science and English (the survey did not look at history teachers).

If teachers are coming up with their own curriculums rather than relying on standards-aligned materials, chances are that every class is learning different things, Kaufman said.

“Some modification feels healthy to me and important,” she said. But, she added, there should be some foundational content that is aligned with what the state says a student should learn in a particular grade.

Off-the-shelf curriculums don’t meet all students’ needs

Teachers of students in special education and of students learning English, in particular, complain that curriculum materials are not sufficiently attuned to those children’s needs.

Simone Gordon, who teaches English as a new language to fourth and fifth graders at PS 361 in Brooklyn, said she has to adapt the district-provided curriculum to her students by using a different book than the one suggested or by breaking a lesson into parts that can be easily understood by her students.

Gordon will often bring in books that offer more diverse characters or discuss current events that are not included in the curriculum but are “what students are seeing and witnessing,” she said.

“I like being given the curriculum when there’s flexibility, and then the option to kind of say, ‘I’m going to use this part, but I won’t use that part,’” she said. “It’s nice to be able to say, ‘My students are really interested in what’s going on with climate change. I’m going to do a thematic study on that.’”

Similarly, Sarah Said, who teaches English language learners in School District U-46 in Chicago’s northwest suburbs, said she sees pre-written curriculum as a starting point, then adapts it to what her students need.

“When you have a curriculum that’s been researched and vetted — it’s okay to use it,” she said. “But you have to make it your own.”

Related: Students with disabilities often left out of popular ‘dual-language’ programs

Kate Gutwillig, a special education teacher at PS 134 in New York, acknowledges that tension. In the past when teachers in her district and elsewhere had more freedom to create their own curriculum, she said it felt like a “double-edged sword” because “I know what my kids need but on the other hand, we’re teachers, we’re not curriculum writers.”

Gutwillig, whose school was in the first cohort to roll out a new literacy program, NYC Reads, said the new curriculum is a welcome change from previous ones she’s been given because it was vetted to meet the diverse needs of students. Still, there are gaps when it comes to her students with disabilities.

“Those curriculums were not written specifically for those kids,” she said; they need to be “adjusted or perfected.”

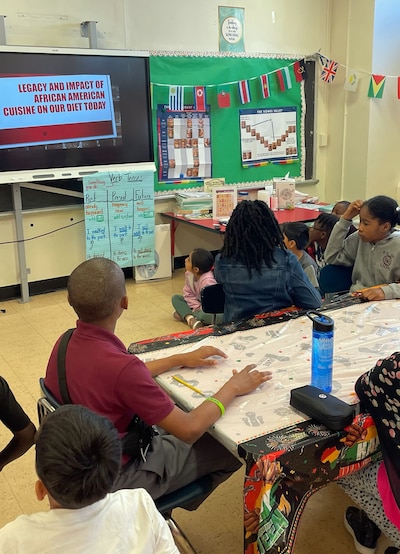

Teachers often modify curriculums to add diversity

The research on the value of a scripted curriculum is important — but teachers say so is the reality they face in the classroom every day. Dier, the teacher in Louisiana, said pre-written, district-provided curriculum materials often don’t cover local history or are not relevant for his students. Recent anti-critical race theory and anti-LGBTQ legislation has also made it harder to teach history in schools, he said.

“My goal is to ensure that the minoritized identities that are so often excluded from, in terms of curriculum, find their space,” he said. “I don’t see a robust curriculum, at the district or state level that ensures that, so that’s why I always want autonomy over my own materials.”

Dier said he isn’t just picking random materials for his classes. He uses the A.P. U.S. history curriculum and Louisiana’s U.S. History state standards and what will appear on the state assessment, and mixes those with current events and history he thinks his students should know.

“I look at the two curricula that I have to use, and then I try to teach the history that is usually pushed to the margins and not included in that framework,” Dier said.

Related: Many high school math teachers cobble together their own instructional materials from the internet and elsewhere, a survey finds

Still, he said that teachers who create their own curriculum must make it transparent and accessible to parents, students, and administrators. Dier said he creates a public Google calendar at the start of every school year that includes the materials he’s teaching “so people know these are still materials of high caliber, quality, and rigor.”

In some districts, teachers are pushing for a bigger role in selecting or developing curriculum so they can provide better materials for their students.

Petrina Miller is a transitional kindergarten teacher at the 116th Street Elementary School who has been teaching at Los Angeles Unified School District for 26 years. Her district is slowly rolling out the Core Knowledge Language Arts, a new curriculum based in research on how students learn to read. She said it doesn’t necessarily work for all students.

The curriculum is split into two parts, skill-based and knowledge-based; the latter “is really not student-centered,” she said. “It is the strangest, most detached unit that makes no sense.” The unit includes lessons on kings and queens — but only “talking about the European kings” — and on Christopher Columbus, which was “just revisionist history, and it was just horrible,” she said.

“I’m not teaching them that, it’s not even true. We just can’t do that,” she said. Instead of telling teachers to follow a curriculum as written, without review, administrators have to get teacher and student buy-in, she said.

After her normal workday, Miller said she goes home and spends about two hours making worksheets and activities. She also spends hundreds of dollars of her own money to make the curriculum more engaging. For the unit on kings and queens, for example, Miller and other teachers hosted a ball and bought hats and crowns for students that featured favorite characters like the princess from Super Mario Bros.

Walsh, of Amplify, said the company, which produces the Core Knowledge curriculum, tries to ensure that it contains materials that reflect and speak to students from many different backgrounds. She said the company also hopes it is “expanding their view of the world.” Units like the one on kings and queens, she said, “ignite students’ imagination about things they don’t know anything about.”

In Los Angeles, Miller is part of a small educator-led campaign, informally launched this year at her school, to involve teachers in reviewing curriculum and other materials to ensure they are culturally relevant. The campaign got the attention of LAUSD school board members and the district, she said. Educators hope it will result in a bigger role for teachers in the buying process for new curriculum programs going forward.

“My students are mostly Latino and African American, and they don’t see themselves in the curriculum,” she said. “It’s hard for them to connect with it.

“It’s teachers that are on the front lines,” she added. “They think of things that maybe someone who hasn’t been in the classroom for a while won’t think of.”

This story about teacher curriculum was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.