Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

When crossing a busy street kept a child from catching the bus, George J. West Elementary School Principal Lisa Vargas-Sinapi had a practical solution: Let’s move the bus stop.

When kids are sick, they’re offered appointments at the school’s health clinic.

And if families share plans to take children on an extended vacation, Vargas-Sinapi explains why that could hurt their education and helps identify child care so they can stay in school.

“We do walk a fine line,” Vargas-Sinapi said. “We keep the expectation, but we’re offering the support — whatever that may be.”

There’s no lone cause of the absenteeism crisis, and no catchall solution either. But one factor for improving school’s attendance is constant — effort.

In Rhode Island, attendance expectations are front and center, reactions to potential problems are swift, and everyone from mayors to doctors stresses the issue. When students miss school, it shows up right away on a dashboard for anyone to see. The governor checks the dashboard several times a day, and schools get a call if he spots a problem. Meanwhile, school staff like Vargas-Sinapi are solving problems big and small that keep kids from coming to school.

Experts say this kind of comprehensive approach is what it takes to move the needle on chronic absenteeism. Rhode Island’s work has earned praise from the White House and was spotlighted by a bipartisan coalition urging schools to prioritize better attendance. And other states like Nevada and Hawaii have reached out to Rhode Island to learn about its strategies.

But state and school leaders say they still have a lot of work to do to get more kids in school — and to keep them there. Sustaining the momentum is hard, especially as schools get closer to pre-pandemic rates of absenteeism, leaving the most challenging attendance issues to solve.

“We are not taking our foot off the gas,” said Angélica Infante-Green, Rhode Island’s education commissioner. “We don’t want people to think: ‘OK, we’re good enough.’ It’s not good enough.”

Why Rhode Island’s attendance model stands out

Before the pandemic, 19% of Rhode Island students were chronically absent, meaning they’d missed 18 or more days of school. That rate shot up to 34% during the 2021-22 school year — when absenteeism peaked across the nation — then dropped to 29% the following year. It was the fourth-largest decline among states that year, according to data compiled by The Associated Press and Stanford University Professor Thomas Dee.

Last school year, Rhode Island’s rate dipped again to 25%.

Education policy experts who’ve examined Rhode Island’s attendance strategy say there are two key components that make it stand out.

The first is the Rhode Island Department of Education’s public “leaderboard” that displays attendance metrics for every school. It updates daily and is connected to how students are performing academically. Everyone from parents to mayors can see how kids who are absent a lot tend to score worse in reading and math.

“It has been shocking for people,” Infante-Green said. “When we say ‘every day counts,’ now they see the difference.”

The second is a push to get people outside of schools working to reduce chronic absenteeism. Governor Dan McKee, a Democrat who has made improving attendance a statewide priority, asked mayors and town managers to sign an agreement listing concrete steps they’d take to boost attendance, such as offering kids leadership opportunities in their hometowns. In return, they’d be eligible for a new state grant that can be used to build and expand community centers that offer services like tutoring. All but one signed on.

Other state departments got involved, too. Rhode Island’s secretary of commerce asked local businesses not to schedule high schoolers to work during school hours, and the health department tasked pediatricians with asking families about how often their kids miss school when they come in for a check-up.

That’s a real shift from the past, when educators tackled absenteeism mostly on their own, said Thomas Toch, the director of FutureEd, a Georgetown University think tank.

“One of the oddly silver linings of the pandemic is that it has helped policymakers, both within education and without, understand that the education of students is a community responsibility,” said Toch, whose think tank published a report this month about Rhode Island’s attendance work. “There are many other student- and family-serving public entities and the private sector, as well, in the form of employers, who have an important role to play in getting kids to school.”

Prior to the pandemic, 37% of students in Providence Public Schools were chronically absent. That spiked to 57% during the 2021-22 school year, then dropped over the next two years, eventually hitting 36% last school year.

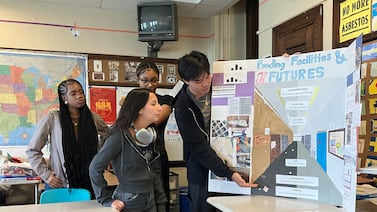

George J. West was among the most improved. After peaking at 58% three years ago, the school brought chronic absenteeism down to 29% last school year.

District and school leaders credit that drop to a few strategies. Officials formed a district-level attendance team to support teams already working in schools, and started using a new data platform that made it easier to flag students as they racked up absences. Staff used data to pinpoint which kids would benefit most from a home visit before knocking on doors.

Schools paid attention to younger children, in particular. Nationally, absenteeism in kindergarten has been especially high.

At Providence’s Asa Messer Elementary, the school social worker called the parents of kindergartners who weren’t showing up regularly to see if there was any support the school could provide, while emphasizing that kids who miss lots of kindergarten tended to be absent a lot in the school’s later grades too.

“Once parents realize that, then it’s like: ‘Whoa, let me get my child to school,’” said Cassandra Henderson, Asa Messer’s principal.

Providence uses incentives and inclusion to boost attendance

One of the most difficult things about the absenteeism crisis is the number of factors driving it.

A parent may be struggling to get their child to school on time between jobs, or a teen may be missing class to care for a younger sibling. Pressure to work, mental health issues, and fears about falling behind at school can all keep kids from attending.

No one intervention solves all of those issues, and it’s not uncommon for schools to find that none of their attendance strategies are particularly effective, according to research released Tuesday by the RAND Corporation.

In Providence, working with a parent’s schedule is crucial, said Carina Pinto de Chacon, the district’s chief of family and community engagement.

A parent might need an early dropoff or a late pickup time. Finding a child an after-school slot or transferring siblings so they’re in the same building could be a big boost. Asa Messer Elementary helped one anxious second grader who missed a lot of school ease in with a shortened schedule and check-ins with the social worker.

Some Providence schools even deployed parents or school staff to pick up kids at their homes and walk them to school — dubbed a “walking school bus.” Some student advisory council members also started calling classmates to see if they needed a ride, Pinto de Chacon said.

Rewards for improved attendance, like pizza parties and gift cards, have also been helpful.

Still, school staff say many of the incentives kids like best don’t cost anything.

At George J. West Elementary, Vargas-Sinapi spun a wheel to award prizes like extra recess or computer time. At Asa Messer, kids got shoutouts for improved attendance over the loudspeaker or a chance to play freeze dance with their principal. Sometimes, the attendance team would “bum rush a classroom” to give kids high-fives and little gifts in an “Oprah-type of thing.”

“Students would then be a positive influence on their peers,” Henderson said.

Henderson also created a student council and invited kids to participate who wouldn’t normally be selected. Knowing they had to show up to make a meeting helped boost attendance.

And providing tutoring to English learners helped them bond with classmates, feel less anxious about language barriers, and enjoy coming to school more.

The Providence district’s goal is to lower chronic absenteeism to 20% over the next two years — nearly as low as the pre-pandemic rate in Rhode Island.

George J. West identified 56 students who improved their attendance a lot last school year, but still missed more than 18 days. The school’s counselor called their families this summer to see how the school could help them get out of that chronically absent category this year.

“We encouraged them: ‘You did a great job getting those kids here,’” said Assistant Principal Mary Bergeron. But then came the second part of the school’s message: “They are not where they need to be yet.”

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.