When I started teaching in 2003, the cell phone was an oddity in the classroom. At that time, trying to send a text, let alone access the internet, on your phone was clumsy at best. I remember when a student tried sneaking a phone into the Bronx high school where I was teaching, neatly tucking the device between two pieces of sandwich bread. The phone couldn’t get past the metal detectors at the door.

Of course, in the past two decades, our relationship to these devices has changed radically. Since returning to the classroom after the COVID school shutdowns, cell phones seem to function as almost an extra limb for my students, an ever-present extension of both their body and mind.

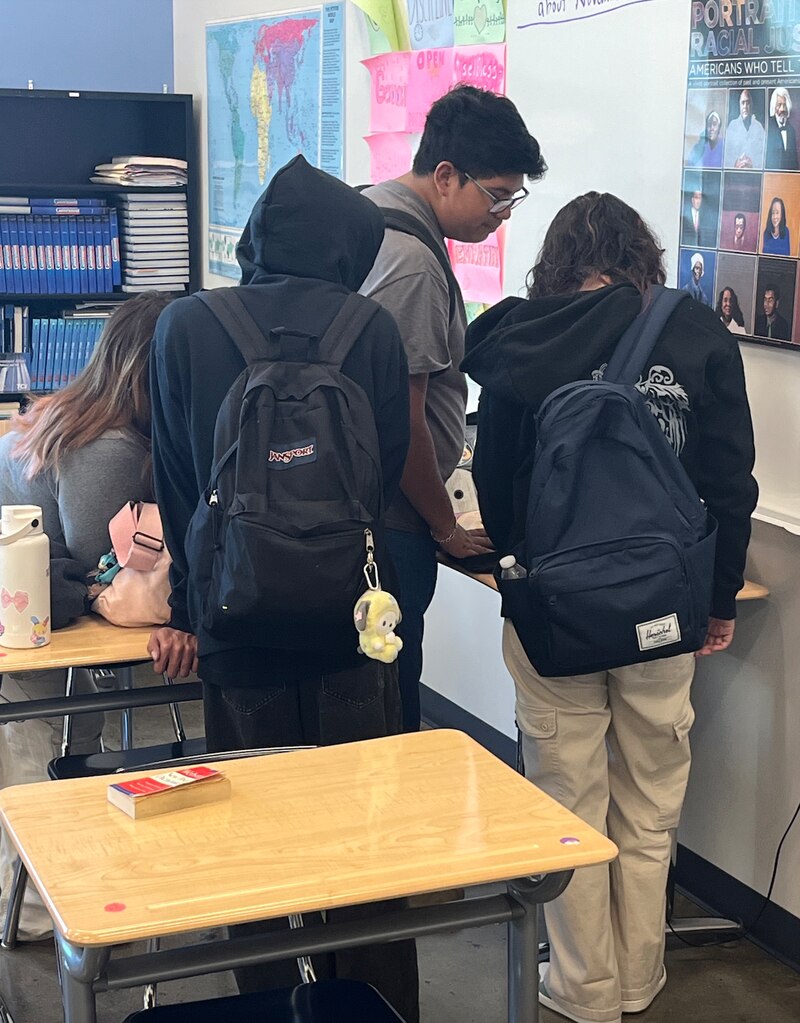

And they have become the biggest window into where American culture sits today. During lunch break, passing periods, and before and after school, we would find students sitting by themselves, watching a movie or playing a video game. Even more bizarrely, we’d see them sitting together, faces buried in their phone; they were isolated even in communal spaces. It’s clear that teens — and adults, too — are ceding real-life exploration, discovery, and connection to our devices.

In a change of practice — and one that more districts and schools are adopting — the South Los Angeles public charter high school where I’ve taught for the past 15 years decided last spring that for the 2024-2025 school year, we would be a phone-free school. The policy came with a recognition that our students deserve more: more space to be present in the classroom, more opportunity to engage with each other, and more time away from the screens that we’re all consumed with.

This year, our school has a new library of books, games, and athletic equipment to encourage students to engage without screens.

In my classroom, gone are the cubbies where students left their phones at the door. In the spirit of “out with the new, in with the old,” and looking for ways to bring novel experiences to my students, I brought in an old boombox and a hefty book of hundreds of CDs. The albums had been languishing in my garage, gathering dust, for a solid decade.

My first flip through the CDs brought some nice surprises — some rare Wilco bootlegs from the early aughts, some mixes friends had made going back to the ’90s, and a smattering of ’90s hip-hop. I told my students that they should come in and pop in a CD in the morning before school or at lunch and expected … well, I’m not sure what I expected. At minimum, I thought they might discover some new old music or get a laugh at my decidedly middle-aged CD collection (see: The Roots, Ben Harper and the Grateful Dead).

Since school started a few weeks ago, students have started to file in, asking to play a CD. Some choices are more predictable — The Beatles and Bob Marley, always timeless — and others are less so. What I’ve been most stunned by, though, is that each choice is an entry point to an unexpected conversation — a reminder of how life was before the phone in our pocket answered every question and satiated every desire (and back when you had to actually read the CD liner notes to figure out the lyrics).

... our students deserve more: more space to be present in the classroom, more opportunity to engage with each other, and more time away from the screens that we’re all consumed with.

A Pearl Jam CD leads to a story of the magazine I created in seventh grade, called Dissident, all about the newly ascendant grunge band. A Counting Crows CD reminds me of the concert where the person next to me sang every sad, heavy lyric at the top of her lungs. My students and I are connecting over music, yes; more than that, though, we’re connecting in ways that felt all but lost these past few years when the default was the screen.

They are seeing more of me — not an online me, filtered through Google Classroom or Loom or some other ed tech app I could never figure out — but actually me. My students, born into the MP3 era, have started bringing CDs from home, along with stories of their parents and cousins and swap meets. And those stories beget stories about what they like to do and who they want to be.

As we embark on their college applications season — with its personal statements and teacher recommendations — I’m optimistic I’ll have some new windows into their inner selves.

I’m hoping the CDs continue to be a draw for my students, bringing more of them into the kind of analog dialogue that they — and I and all of us — need more of in the smartphone era. It’s likely to foster new ideas and take me to new places, maybe even a thrift store or two to find some more new old technology.

On a recent morning, I brought a copy of the New York Times, a real print paper straight from my front yard. I’m hopeful that the newspaper will be a conversation-starter of its own, filling my classroom with questions, connections, and laughter for good measure.

Joel Snyder is a government and economics teacher in the Florence-Firestone neighborhood of Los Angeles. In the 22 years since he started teaching and stopped listening to CDs, he has continued to listen to exactly the same music.