“There’s another swastika in the boy’s bathroom,” Gordon, a high school senior, said as he entered my classroom. “It’s carved into the toilet paper dispenser.”

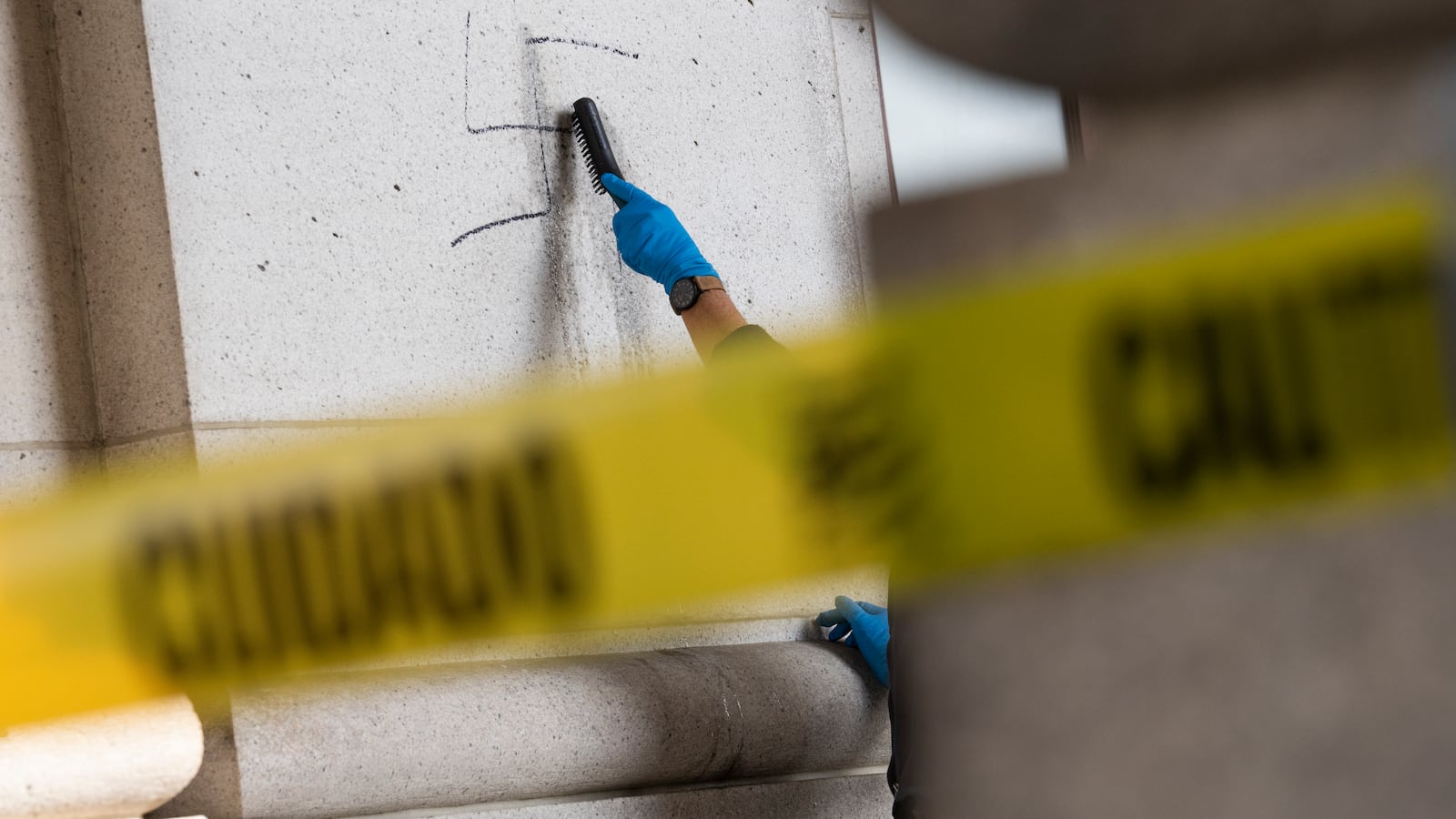

This was just the latest in a rash of swastikas drawn in the bathrooms in the junior-senior high school in rural Wisconsin where I was teaching.

In my 19 years as an educator, I had never experienced anything like this. And though I taught about the Holocaust for my entire career, I felt ill-equipped to respond to and teach about contemporary antisemitism. As a school, we also struggled to respond to antisemitism in our midst.

Antisemitism has increased in Wisconsin and the United States. An Anti-Defamation League report revealed that antisemitic incidents increased by 140 percent nationally in 2023 to their highest level since 1979. The Milwaukee Jewish Federation reported antisemitic incidents have risen in Wisconsin, marking a cumulative increase of 570 percent since 2015. This included a dramatic rise in antisemitism in schools, including mine.

A few years ago, when swastikas and other antisemitic hate speech began appearing in our school, administrators and colleagues suggested the need for more Holocaust education. They often came to me to address the issue in my social studies classes.

I know from conversations with fellow teachers across the state and country that this is not unique to my community. Antisemitism is increasingly prevalent in K-12 schools, and the Israel-Hamas War has only intensified antisemitic — and Islamophobic — hate speech.

In a reflection activity that I conducted in my classroom after one incident of swastika graffiti, many students suggested that the swastikas are being drawn by kids who, in their words, “are trying to be funny” or “don’t understand what swastikas mean.” Although most students seemed to want to minimize or dismiss this hate speech as juvenile pranks or misunderstandings, one senior reflected: “I think there are more Jewish students in the school than we know about, and they are the ones drawing them.”

This statement, suggesting Jewish students were drawing swastikas, was not simply an innocent misunderstanding; rather, it was part of a deeper, pervasive set of antisemitic myths that Jews are responsible for the hate directed their way. At their extreme is the claim that Jews caused the Holocaust. A 2020 Claims Conference survey found that belief in these types of myths is growing and that they are held by about one in 10 American adults under the age of 40.

Like my students, many colleagues also sought to minimize the antisemitic graffiti. Despite policies against hate speech, administrators routinely dismissed the idea of punishing the culprits of the swastika drawings if they were ever identified. Instead, they talked about the need for more Holocaust education. “This is a clear learning opportunity,” they insisted.

There was a time when I largely agreed with them.

Holocaust education is already a widely respected mainstay of the curriculum. Wisconsin recently became one of 29 states to mandate Holocaust and genocide education in all public middle and high schools. By the time they were seniors and took my Genocide and Human Rights course, students had studied the Holocaust multiple times across their mandatory middle and secondary social studies and English classes. And according to the Claims Conference study, Wisconsin Millenials and Gen Z scored highest in Holocaust awareness in the United States.

Yet, swastikas kept appearing in the bathrooms at our school.

While my students had studied the Holocaust in various classes over several years, I found they actually knew relatively little about the history of antisemitism, an ancient hatred and conspiracy theory that stretches back millennia. “Why did the Nazis hate the Jews?” was a common question. Students struggled even to recognize or define the term “antisemitism.” They knew even less about the history of antisemitism in the United States or its manifestations around the world today.

Even the most comprehensive Holocaust education may not adequately address how we are seeing antisemitism appear today. Students need to learn about antisemitism today, as either part of or in addition to their Holocaust education.

While Holocaust curricula abound, there is still a relative lack of resources for teachers on contemporary antisemitism. Echoes & Reflections — a Holocaust education partnership program of the Anti-Defamation League, USC Shoah Foundation, and Israel’s Holocaust Memorial, Yad Vashem — has a comprehensive set of lesson plans and resources on the topic called the Gringlas Unit on Contemporary Antisemitism.

Named for a family of Holocaust victims — some who perished and others who survived — the Gringlas Unit begins with the history of antisemitism before and during the Holocaust, before having students examine examples of antisemitic myths and memes on social media, as well as rhetoric and images from current events. The unit builds students’ awareness of antisemitism so they can recognize and challenge it in their daily lives, helping students untangle intersecting forms of hate speech and ideologies.

There is no shortage of examples from which to draw, from musicians threatening Jews on social media to politicians insinuating American Jews are disloyal to tired tropes about Jewish money or power. My students quickly became adept at recognizing antisemitism. They were able to share examples of hate speech they had seen just the night before on social media or, especially, on online gaming platforms. I encouraged students to speak out against antisemitism when they see it in our school and community.

A 2024 study on the Gringlas Unit showed that learning about contemporary antisemitism increases students’ knowledge of the Holocaust, raises awareness about the ways antisemitism shows up today, fosters empathy towards victims of hateful attacks, and inspires students to combat antisemitism when they see it.

This has been my experience as well. After learning about contemporary antisemitism, my students were able not only to recognize but also to speak out against it. During the 2023-2024 school year, no swastikas appeared in the bathrooms, and we also saw a dramatic decrease in the other hate speech in the school. The story of our school community suggests that this sort of intentional intervention can make a difference.

While Holocaust education must remain an important part of American education, addressing contemporary antisemitism demands that we explicitly teach about it.

George Dalbo, Ph.D., is a visiting assistant professor at Beloit College and a research fellow at the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Minnesota. Previously, he was a high school social studies teacher in Wisconsin and Minnesota.