This story was published in collaboration with Headway, a new initiative at The New York Times. Chalkbeat and Headway have been posing questions about the presidential election to educators and high school students since February. We have heard from nearly 1,000 students and 200 teachers across the nation.

Inside a North Philadelphia high school, a class of 11th graders talked frankly about the most controversial aspects of the 2024 election: abortion, Project 2025, the prospect of the first female president.

Nearly 650 miles away at a middle school in Indianapolis, an eighth grade teacher avoided talk of former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris, holding a mock debate about cellphones and cafeteria food instead.

As the presidential election took over classroom conversations this fall, Chalkbeat and Headway at The New York Times listened in across the U.S. as students considered the stakes of the race and, for some, their own roles as first-time voters.

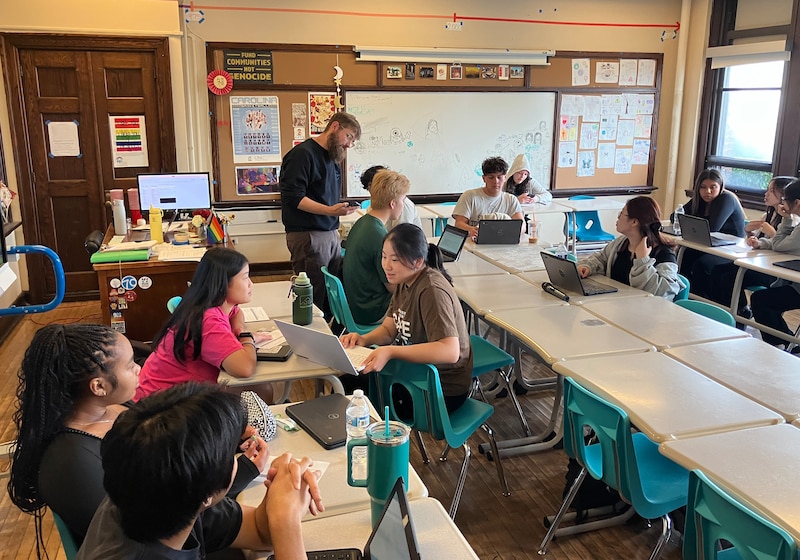

What we found was a mosaic of creative approaches from educators like Charlie McGeehan, a social studies teacher at the Academy at Palumbo, a Philadelphia high school. He’s challenged his students to debate one another on whether voting is a right or a privilege — or something altogether different.

The “voting is important” message tends to fall flat, he’s found, “unless you actually have them learn about it and come to that message on their own.”

Here’s a look inside four of the classrooms that Chalkbeat and Headway visited.

Crosstown High School, Memphis, Tennessee

The AP U.S. Government students were given a simple but unusual assignment: sip Pellegrino, nibble on cheese and crackers, and schmooze.

It was part of teacher Kat McRitchie’s election simulation, her hands-on approach to showing students the inner workings of democracy. This fall, each student took on a fictional role and acted out the pivotal moments in a presidential campaign, from primary speeches all the way to counting votes.

“They get the chance to see the interaction of individuals and institutions and to see how power flows through the process,” said McRitchie, a 21-year educator. “They feel like they have an inside look at how elections work.”

On this September day, her students were acting out a less traditional focus of a campaign lesson: D.C. networking party. But before they could tuck into the snacks, McRitchie challenged the students to consider a few questions. What would their characters — conservative and liberal candidates, campaign managers, media, and representatives of special interest groups — want to talk about? What would they want to get out of the other attendees?

“At this party, you all are going to shmooze and hustle each other,” she said. “At events like these, you can see power moving.”

Her students still track the presidential race, analyzing the real-life debates and stump speeches and conventions. “We’re able to see parallels,” said Carolina Calvo, 18, who chose the role of Democratic campaign manager. “It’s clearer how this works in the real world.”

John Bush, 18, was tasked with playing the liberal presidential candidate, Gov. Chip Rhodes. Bush plans to vote for the first time and credits the simulation with broadening his perspective.

“I think when things are taught in the classroom, it can be from a greater variety of sources than I wouldn’t interact with just by myself,” he said. “And maybe helps against a little bit of polarization.”

Murrell Dobbins Career and Technical Education High School, Philadelphia

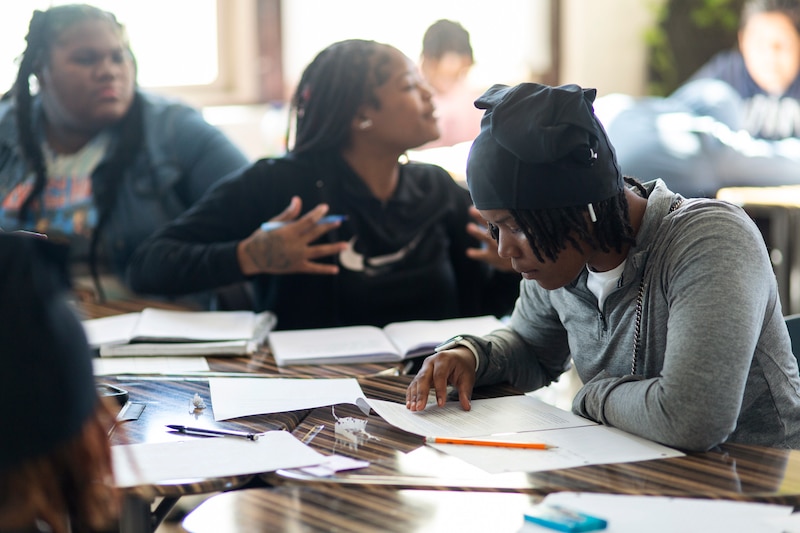

Inside a 7:30 a.m. 11th grade U.S. history class, most students aren’t familiar with the differences between Republicans and Democrats. They don’t know the parties’ symbols, a donkey and an elephant. And only three out of a dozen students who showed up one recent September day said they would vote, if they were old enough.

Enter John Winters, known as Brother John — and, because this is Philadelphia, a lesson involving cheesesteaks.

“Democrats,” he told the students, “tend to generally have a similar point of view of the world, and Republicans have a similar point of view politically as well.” He then projected side-by-side pictures of a cheesesteak and Buffalo wings. “Some people are gonna be cheesesteak people, and some like Buffalo wings,” he said.

To help students understand where they fall, the class drills down into political ideology. Winters gave students a series of statements to rate from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” including:

- “The government should use taxpayer’ money to provide free day care for all parents.”

- “The U.S. government should grant reparations to all Black people for the enslavement of Africans in this country.”

- “A woman should be able to have an abortion without anyone else’s permission.”

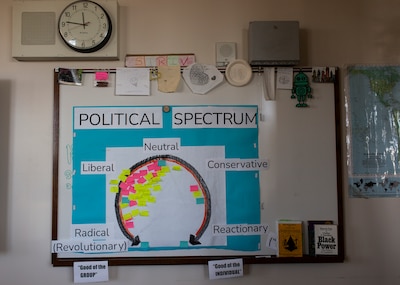

Winters then rolled out a bulletin board with a chart titled “political spectrum,” and students placed pink sticky notes where their answers landed on the spectrum. (Most fit on the left, with two students leaning conservative.)

Winters has taught for five years at Dobbins, an 800-student technical school in the Philadelphia ZIP code with the lowest household income. Its student enrollment is 89% Black, with most of the rest being Hispanic or multi-racial.

While this area is solidly Democratic, its usually reliable voter turnout rates have slumped in recent elections. This is a huge concern for Democrats, as President Joe Biden won Pennsylvania by just one percentage point in 2020.

Young voters are expected to play a pivotal role in the outcome of the race, particularly in some swing states like Pennsylvania. And while Winters’ students may not think they care about politics or feel they align with one of the two major parties, that doesn’t mean they don’t care about the issues. Discussions grew heated at times in Winters’ 11:30 a.m. session of the class, after one young man shrugged off abortion as a 1 or 2 on a scale up to 10. A young woman vehemently objected.

“I don’t put it as 8, 9 or 10. I’d put it higher. Like 15,” she said. “You’re not gonna let anybody be in charge of our country, in charge of a woman’s body, you can’t do that. Men already think they can overpower women.”

Westlane Middle School, Indianapolis

It was hours before the vice presidential debate inside Kevin Melrose’s eighth grade social studies class. But there would be no talk of J.D. Vance or Tim Walz.

Social studies teachers at the school avoid instruction about national politics in order to remain nonpartisan, said Melrose, per direction from the district. Washington Township, where Westlane is located, is a politically and socioeconomically diverse district, Melrose notes, even though Marion County as a whole is a blue dot inside red Indiana.

And while the state did not pass a divisive concepts law that would have limited teachers’ abilities to discuss race and other topics, the scrutiny and charged rhetoric of the last few years have led teachers to tread carefully. It’s a common stance: Fifty-eight percent of K-12 teachers surveyed by the EdWeek Research Center this summer said they do not plan to talk about the election in their classrooms. Of those respondents, 22% said they were worried about parent complaints, while another 19% didn’t think discussions could be respectful.

Melrose, the chair of the school’s social studies department, has focused on teaching democracy through student council elections. All eighth graders break into groups of four — a president, vice president, and two campaign managers — and hold classroom elections with campaign posters, videos, and in-class debates.

The winning candidates from each classroom face off for the role of eighth grade class president, who effectively leads the student council.

Despite the moratorium, students are paying attention to state and national politics. Some students even watched the presidential debates to get a sense of what to do as candidates. And Melrose doesn’t stop them from discussing issues that directly affect them.

Many of the students’ presidential platforms include typical school election fare such as promises of better cafeteria food and changes to the dress code. This year, many also promise to convince Westlane to loosen cellphone restrictions. Indiana this year passed a law requiring schools to ban cell phones during instructional time, but Westlane has gone further and required students to put phones in their lockers at the beginning of the day, worrying students who want easier access to their phones in the event of an emergency, like a school shooting.

“The world has changed,” said one candidate, Travis Smith. “There’s more shootings and stuff like that than at any time before.”

Other students challenged the candidates on how, exactly, they would enact their policies. If the cellphone ban is a state law, they ask, what can an eighth grade class president really do about it?

But, Melrose pointed out later, the student council has had big wins. Members successfully opened up field trips to more students, and a few days after the debates, the eighth graders were due to head to D.C.

East Bronx Academy for the Future, Bronx, N.Y.

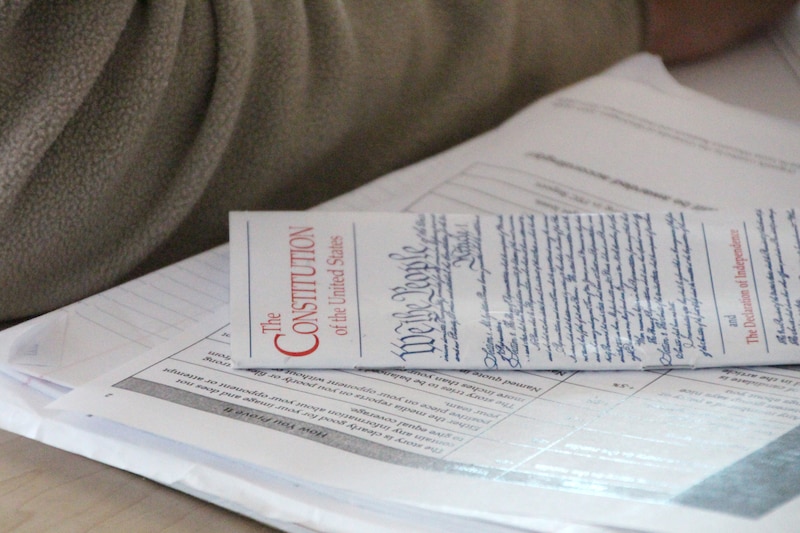

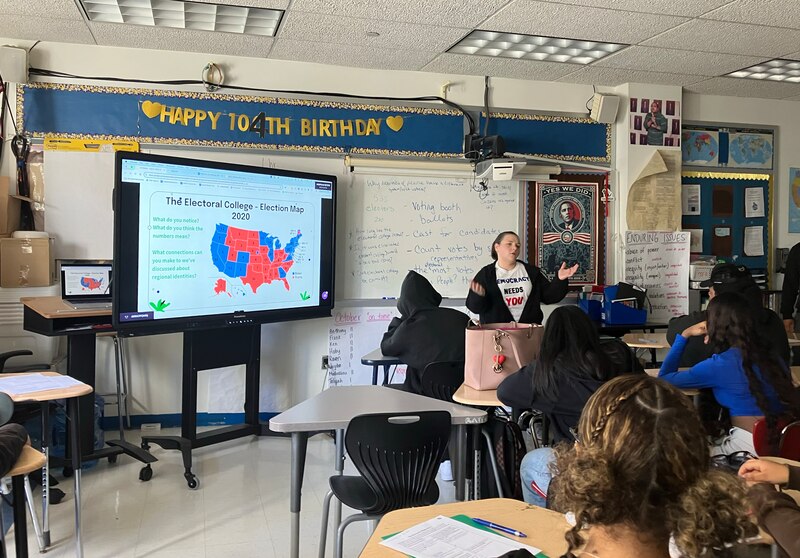

In Christine Montera’s 11th grade U.S. History class, the past is used to explain the present.

Montera, social studies department chair at the grades 8-12 school, recently explored with her students elements of the distant past that are still being felt today: the ways regional identities developed in colonial America and the formation of the electoral college in 1787.

“My goal in teaching the election in history class is to help students understand that we truly did not fall out of a coconut tree into a current election cycle,” Montera said, referencing a viral quote from Vice President Kamala Harris, “and that all of it is based on the context and history of our country.”

This background helped her students answer two urgent questions on Tuesday: Is the electoral college democratic? And does it help or hurt democracy today?

She pulled up an electoral college map of the 2020 presidential election and asked her class, “What do you notice about this map?”

Students chimed in that it looked like the Trump supporters were clustered in the middle of the map, and that there were different numbers around the map. Montera asked what those numbers meant, and students tried to guess before Montera explained that the number of electoral votes a state receives is based on their population size.

Jannatul Urmi, 16, noticed that most of the southern states were red.

“Good, what do you think that says about their regional identity?” Montera asked.

“Maybe they’re more traditional. They’re more religious, so that’s why they’re voting for Donald Trump,” Urmi offered.

The more the students learned about the electoral college through a video and then a worksheet reinforcing what they’d learned, the more questions they had.

“Can the electoral college be corrupted?” asked Arisnoely Vivaldo, 16.

“Why does it still exist if so many people are against it?” Urmi wondered.

“What happens if the elector doesn’t follow the majority?” asked Alexander Cataquet, 16.

“They’d go to jail, right?” Urmi responded to him.

Then the class returned to one of Montera’s guiding questions: Is the electoral college helpful or hurtful to democracy? Many students settled on hurtful, critiquing that individual votes don’t have equal weights in each state and pointing out the possibility of corruption if an elector goes rogue.

When asked what stuck with them from Tuesday’s lesson, students said they were offered different perspectives, which in turn changed the way they think about the election and the role different people play in it.

“I never realized how much the background of a region affects the way society is now,” said Vivaldo. “Like certain social norms and ideas have passed down throughout the generations.”

Thinking about these regional identities made some students reflect on how they have come to their own political beliefs.

“I feel like I wasn’t too big on political stuff, but I feel like knowing more of the background helped me understand and have my own opinion,” said Emma Alvarado, 16, “and not just listen to what everybody else thinks around me.”