This story was published in collaboration with Headway, a new initiative at The New York Times. Chalkbeat and Headway have been posing questions about the presidential election to educators and high school students since February. We have heard from more than 1,000 students and 200 teachers across the nation.

A doctored GIF of a Parkland shooting survivor ripping up the Constitution. A fake story about a firefighter jailed for praying at the scene of a fire, branded as if it were from ABC News. An image of a shark swimming on a flooded highway.

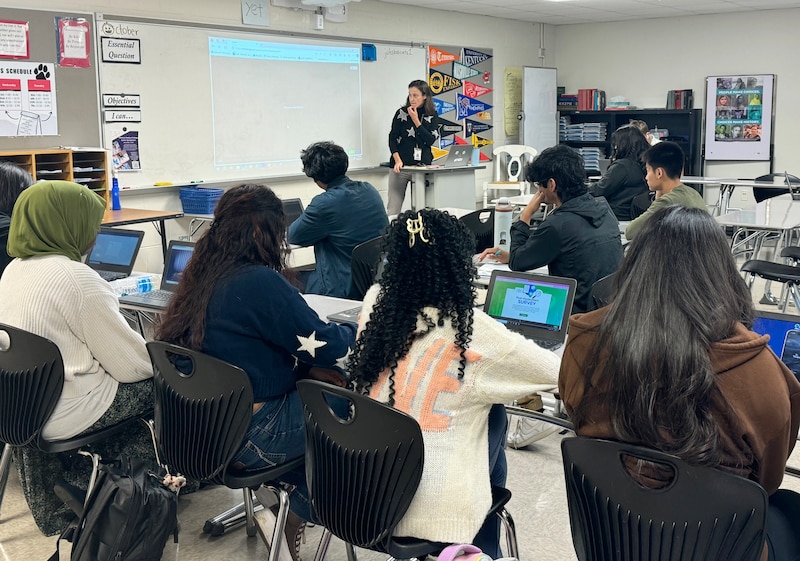

Those and other examples of misinformation students might encounter flashed on screen during high school teacher Lacey Galbraith’s writing class in Nashville, Tennessee.

But Galbraith wanted to bring it closer to home. So she paused the video to show her students something factual: a Nashville TV station’s recent piece about the federal indictment of two Russian nationals. They’re accused of hiring a Tennessee-based company to create and disseminate propaganda and disinformation across U.S. social media platforms with the goal of amplifying domestic divisions.

“You think this stuff is happening far away,” she said. “But it can happen here.”

Teachers in subjects ranging from language arts, math, and philosophy are taking academic questions about symbolism, sample size in polling, and discerning the truth, then applying them to the information students see every day on their phones.

There is no precise accounting of media literacy classes. But they appear to be growing more common as teachers feel compelled to help students distinguish fact from fiction. Students’ ability to do so can shape their everyday actions and relationships. But this year’s presidential election, which has generated a seemingly endless stream of doctored images and out-of-context video clips, has given these lessons more urgency: Some of these students are voting for the first time.

Supporters of every kind of political position share false information, but former President Donald Trump’s campaign has promoted a well-documented torrent of falsehoods. The act of fact-checking is often perceived as partisan. Some Republicans have objected to media literacy lessons as potentially introducing a liberal bias. Studies find that people with strong political views are more likely to believe information that aligns with their views, even when they’ve had media literacy training.

All that leaves teachers with a tough job. They don’t want to be accused of partisanship or indoctrination, especially in states that have adopted “divisive concepts” laws. They also want students to do their own thinking and come to their own conclusions. And they want students to recognize misinformation, even when it comes from a perspective the student might otherwise agree with.

The result is lots of creative and sensitive lesson planning aimed at arming students with real-world skills they can apply to politics or to pop culture memes.

Ultimately, students deserve for these lessons to be part of their education, said Peter Adams, senior vice president of research and design at the News Literacy Project, which provides tools for educators and students.

Young people are living in the “most frenetic, fast-paced information environment in history,” he said. “They didn’t build this information environment. They inherited it. But they have to navigate it as part of their civic engagement.”

As Galbraith’s class wrapped up, one student asked her about the growing sophistication of artificial intelligence, which is rapidly generating inauthentic images and deep fake videos.

Galbraith told the student identifying AI is a larger conversation. She said that for the time being, “if you can’t find it anywhere else, I would wait to share it.”

Taylor Swift, football, and debunking misinformation

A recent survey of more than 1,000 teenagers conducted by the News Literacy Project found that in fact, many young people can detect AI-generated images. But they struggle to distinguish between news, commentary, and advertisements.

A third of respondents thought a photograph coupled with an outrageous claim represented strong evidence for the truth of that claim.

Teens also reported that they regularly encounter conspiracy theories on social media, including the idea that aliens live among us, the Earth is flat, and the 2020 election was rigged or stolen.

Eight in 10 respondents said they believe at least one conspiracy theory. Nearly half said they thought it was more likely than not that the 2024 Super Bowl was rigged. This conspiracy theory alleged that the Chiefs won because tight end Travis Kelce is dating pop icon Taylor Swift.

The consequences can be greater than just someone being wrong. It can lead to disruptions to schools, threats to election workers, and delayed disaster response.

“Misinformation, if you believe it, changes the trajectory of your beliefs and your actions,” said Pamela Brunskill, a former teacher and literacy specialist who trains teachers for the News Literacy Project. “It could erode relationships, and it could also make you go against your best interests.”

One basic countermeasure is known as “prebunking.” This involves helping people recognize when to be skeptical of claims. This strategy can be more effective than debunking something the person already believes, many experts say.

Prebunking can mean teaching students common tricks and tropes, such as sharing alarming video from an old event and claiming it’s from a more recent catastrophe, or photoshopping a message onto a celebrity’s T-shirt.

It can also mean highlighting topics, such as voter fraud, where misinformation is especially prevalent and caution is warranted.

Reverse image searches are a good way to identify images taken out of context, an old-fashioned but very common misinformation technique. Lateral reading, looking for other news sources to confirm an outrageous claim or get another perspective, can help students spot bias and fabrications.

“Critical ignoring” is an important skill too. If something seems sketchy, it’s OK to just keep scrolling.

Teachers in Brunskill’s workshops say one of their biggest challenges is responding to students who already believe something false. Simply telling the student they’re wrong could backfire. She suggests teachers start with questions: Why do you believe that? What evidence do you have?

Using mundane, nonpolitical examples can help take the temperature down a bit and resonate with students who aren’t into politics. One TikTok from the News Literacy Project teaches how to do a reverse image search using the hook of finding furniture for less money before explaining that the same methods can be used to check all kinds of things.

“When you are not emotionally invested, you’re much more likely to be able to reason about the claims,” Brunskill said. Then students will have skills in place “when you are looking at claims that are confrontational and partisan and that do spark your emotional reaction.”

Despite the challenges, teaching election-related misinformation is important, Brunskill said: “I think we need to find ways to incorporate it into our classrooms.”

‘Baby Shark’: From earworm to media literacy tool

To recognize misinformation, it helps to have basic media literacy, such as knowing the difference between reported news, opinion pieces, and entertainment, and to recognize what makes certain sources more credible.

Tara Zimmerman, an assistant professor at Texas Woman’s University, is helping develop a curriculum that helps children do that from a very young age. As a school librarian, she saw other adults assume that children raised on technology would be sophisticated information consumers, when the opposite was true.

One lesson for kindergartners starts with the children’s song “Baby Shark.” Students get their ya-yas out dancing to the song, then settle down to hear some questions.

Are sharks really pink and yellow and green like they are in the video? Are daddy sharks really bigger than mommy sharks? Do sharks really live in family units? Children may know the answers to some of these questions, but not all.

That opens the door for educators to show students where to find factual information about sharks and talk about the purposes of different types of information.

“Does this mean that ‘Baby Shark’ is bad? Absolutely not,” Zimmerman said. “We love it. It’s so much fun. But it’s not the place to go when we want to really learn about real sharks.”

Zimmerman is partnering with Faith Rogow, an educator and curriculum developer, who co-founded the National Association for Media Literacy Education, to test this new curriculum for elementary students in New York, Oklahoma, and Texas.

But don’t call it a misinformation curriculum.

Instead, Zimmerman and her partners call it an Awareness and Critical Thinking Program. They made sure to choose examples that were completely apolitical, avoiding, for example, references to climate change.

“Words like misinformation have become very politicized and hot,” Zimmerman said. “Who are you to teach my child what is misinformation? But who can object to critical thinking?”

Math + civics = knowing when to trust news sources

At New Design High School in New York City, Courtney Ferrell and Liv Roach co-teach Stivics, a combined statistics and civics class.

Students learn about gerrymandering and apportionment and how to read polls. They learn how to use math to analyze social problems and how to spot when statistics are being manipulated.

“This is a class that people can use when they read the newspaper,” Roach said. “And it also reinforces that math is everywhere.”

This year, Ferrell and Roach wanted to incorporate more media literacy as students discussed the 2024 election. Over several days in October, students learned about different types of information and how to assess whether a source was credible. They picked topics they wanted to research and logged the sources that they used.

“Don’t just read the small summary that Google provides. You want to click on the link and get more context about where it was written,” Roach reminded students as they worked in small groups. Wikipedia can be a starting point, the teachers told students, but not their last stop. Click on the citations and read more.

Levi Hogan, 17, decided to research inflation. “The prices are so bad in New York. With seven dollars, if you buy a sandwich, you don’t have money to buy a drink,” he said.

But Levi got discouraged when he read a disclaimer on the website he’d used to compare past and current prices: “CoinNews makes no representations as to the accuracy, completeness, correctness, suitability, or validity of any information on this site.”

Roach said that didn’t necessarily mean the information was wrong. But she advised Levi to check the results against other inflation calculators.

“Since we started taking this class, I feel like I ask more questions about what I’m looking at instead of just going like: ‘Yeah, that’s true,’ and then scrolling to the next thing,” Levi said. “Now I’ll probably start to ask questions like, ‘Is this real or is this fake?’”

When students choose media literacy over Shakespeare

The media literacy class at Mill Creek High School in Gwinnett County, Georgia, developed over several years as educators in the district looked for a way to make English skills feel modern and relevant. Seniors can now use the course to meet the county language arts requirement.

The class includes M.T. Anderson’s 2002 dystopian young adult novel “Feed,” in which brain implants provide children with a steady stream of augmented reality. But lessons more often draw from current media and the internet.

“Our kids, by the time we get them as seniors, have had 12 years of stories and poetry and novels,” said Erin Wilder, who teaches the class. “We tell them: Use those 12 years of language arts skills and we’ll show you how those translate into understanding what you encounter out in the real world.”

In 2022, Georgia adopted a “divisive concepts” law that limits how teachers approach certain topics. But Wilder said that hasn’t changed her lessons.

“We know our students, and we know our parents,” she said. “Our parents pay attention, and as media literacy teachers, we know how to walk the line and how to choose materials.”

Wilder’s students learn about story framing and bias, propaganda, attack ads versus message ads, misinformation and disinformation, conspiracies, and fallacies.

In a recent lesson about political ads, Wilder chose examples from past election cycles — including an infamous 1988 ad about Michael Dukakis’ record on crime — to avoid any appearance of trying to influence her students.

But when it’s time for students to choose ads to analyze, they’re free to pick from the current news cycle. Many do.

“We talk about what makes an ad effective, not whether we agree with it,” Wilder said.

This year, Wilder said, more Mill Creek students opted for the media literacy course than chose British literature.

“I love Shakespeare. I love literature,” Wilder said. “But this is so important too. This is the world. The kids who want more Shakespeare can go to college for that. Everybody needs this.”

Senior Reporter Marta Aldrich and national desk reporting intern Wellington Soares contributed reporting from Nashville and New York City.

Erica Meltzer is Chalkbeat’s national editor based in Colorado. Contact Erica at emeltzer@chalkbeat.org.