In collaboration with the Headway Election Challenge from The New York Times, we’re asking: What should future students of American democracy know about the 2024 election?

“Doomed.” “Baffled.” “Scared.” “Happy.” “I don’t care.” “We are so cooked.”

Those were the reactions to the presidential election result that students scrawled on a white board Wednesday morning inside Joshua Ferguson’s 11th grade government class at Ypsilanti Community High School in Michigan.

Before he knew that former President Donald Trump had won a second term, Ferguson thought he would do a lesson on disinformation in politics. Instead, he gave students room to talk. The most important piece of this lesson, he said, was for his students to feel safe and heard.

“I think that’s my job as a teacher,” he said.

Educators across the country awakened Wednesday to the news of a second Trump presidency, then headed into school buildings where students were feeling everything from elation to shock to despair. Some had carefully scripted lesson plans at the ready. Others, like Ferguson, scrapped what they prepared and simply listened.

For civics and social studies teachers who had been monitoring the 2024 presidential election, Wednesday presented both a pedagogical challenge – and opportunity. Chalkbeat reporters fanned out to schools across the country to see how teachers approached this monumental day.

This story was reported by Caroline Bauman, Gabrielle Birkner, Hannah Dellinger, Jessie Gomez, Dale Mezzacappa, Amelia Pak-Harvey, Carly Sitrin, and Alex Zimmerman.

‘Why do people keep voting for Trump?’

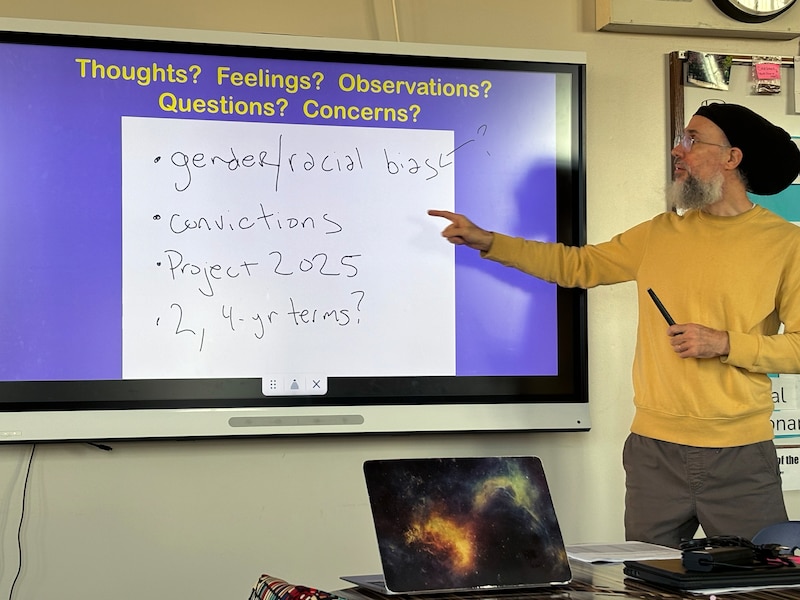

Ahead of his 7:30 a.m. social studies class Wednesday, teacher John Winters had prepared a worksheet to spur conversation.

“As you know, [fill in the blank] has been elected as the next U.S. President,” the sheet read. “Please share your thoughts, feelings, concerns, questions, etc.”

His students at Philadelphia’s Murrell Dobbins Career & Technical Education High School didn’t need much prompting.

“He IS a convicted felon and should’ve never been allowed to run ever again,” wrote one student.

People “don’t want to see a girl/woman be the president,” wrote another.

“Why do people keep voting for Trump? Especially people that he doesn’t even like and is racist towards?” still another wrote.

The responses conveyed dismay and fear among some at the 800-student technical school, which is 89% Black and located in the city’s lowest income ZIP code.

At the end of the class, one junior held back to talk to Winters. Anxiety, even fear, was written all over his face as he struggled for words.

He asked a series of questions, like how many bills a president could pass and how an impeached president could be elected again. Winters answered but sensed there was something larger the boy wanted to know.

“I was born here, but I’m scared for my parents,” he said. “They’re from Haiti. It’s bad there right now.”

Winters reminded him that strongly Democratic Philadelphia has been a sanctuary city, meaning it doesn’t always cooperate with the federal government in enforcing immigration law. He told the young man to clarify with his parents their status. But then, reluctantly, he added: “I can’t lie, it’s a concerning situation.”

The boy put his head down, and slowly walked to his next class.

A rightward shift, especially among boys

At The Global Learning Collaborative, a high school situated in the deep-blue Upper West Side of Manhattan, students reacted to Trump’s victory with a mix of fear, ambivalence — and support.

More than 70% of the school’s students are Latino, and many expressed alarm over Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric. But there was still a sizable number of students who supported the Republican candidate during a mock election held during a Wednesday morning assembly: 136 students voted for Vice President Kamala Harris, while 70 supported Trump.

Junior Alix Torres said she has undocumented relatives and worries about his promise to ramp up deportations.

“I woke up kind of angry this morning,” Torres said, noting that she helped persuade some family members to vote for Harris. “I hope he hears the public and chooses to not go through with that. We built this country.”

Others at The Global Learning Collaborative said they supported Trump or didn’t have a firm opinion of him; nearly all were under 10 years old during his first presidency.

Senior Sara Otero, who is 18, voted for the first time on Tuesday, casting a ballot for the former president. A devout Christian, Otero said she believed Trump would preserve religious liberty, though she hadn’t followed the election closely.

“I wasn’t as educated as I wish I was on the whole thing,” she said.

Harris decisively won New York City, but by a much smaller margin than Biden did in 2020. Civics teacher Martin Gloster said he has seen a rightward shift in political attitudes in his classroom.

“I think teenage boys are really attracted to that strongman presence,” he said.

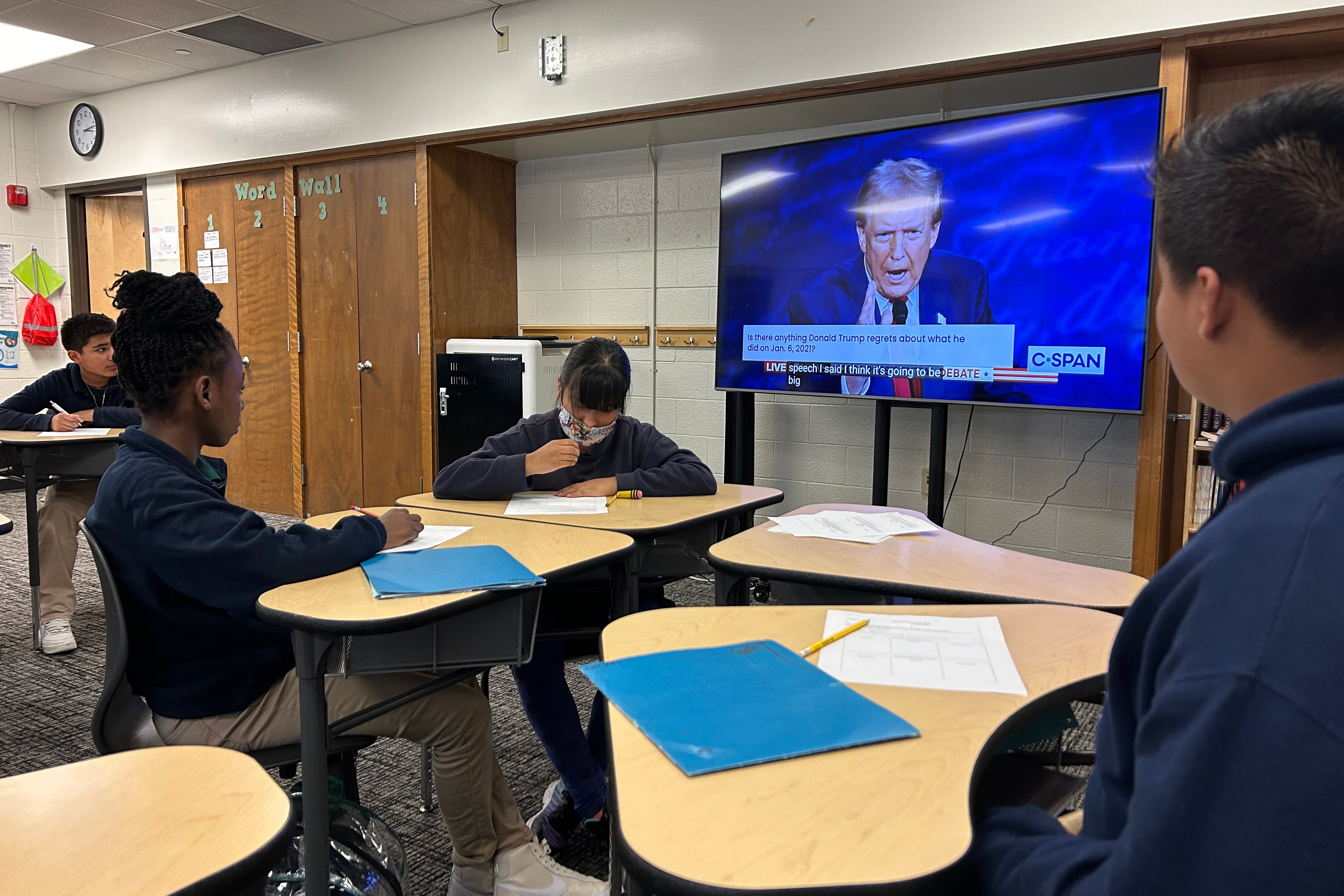

Gloster said he has struggled with teaching contemporary politics, including the presidential debate in which Trump falsely suggested Haitian immigrants were eating cats and dogs. In a class that discussed the debate, one student had faced an arduous journey emigrating from Guatemala, while others were more sympathetic to Trump.

“It’s difficult because obviously I play it down the middle — Trump is just a different thing,” Gloster said. “I’m learning on the fly. I don’t have all the answers.”

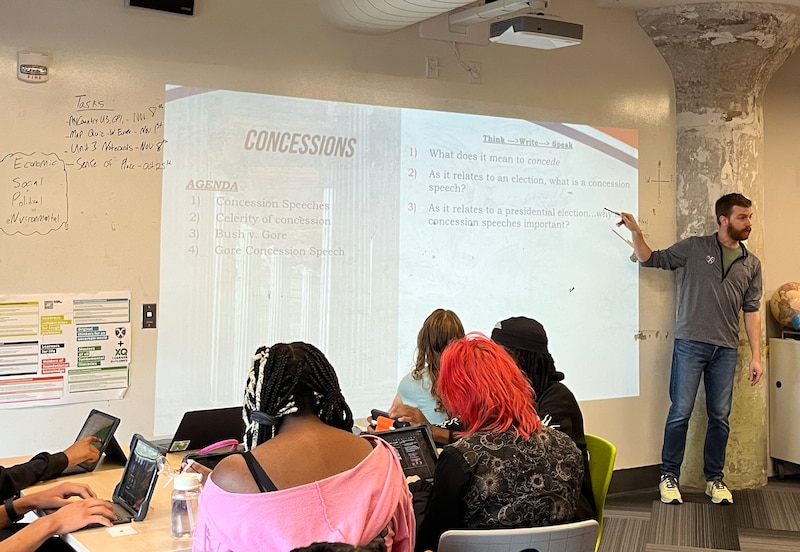

Taking lessons from Gore’s 2000 concession speech

When Reid Stuart arrived for his first class on Wednesday, he had three goals for students: Give space to process this huge political moment, impart tools to combat misinformation online – and watch Al Gore’s concession speech from 2000.

“It’s an incredible speech, by a Tennessean, after a tense moment that calls for unity,” said Stuart, who teaches at Crosstown High School, a diverse public charter school in Memphis, Tennessee. “It feels relevant.”

His students in AP Human Geography settled into class, some joking with each other about the election and others speaking somberly.

Before watching Gore’s 2000 concession speech, Stuart asked: What did his students expect from a conceding presidential candidate?

“To show respect to the other candidate.” “To show respect for the system.” “To actually concede,” students chimed in.

Stuart then asked, “If you are Al Gore, how are you feeling?”

“Cheated.” “Mad.” “Unaccepting of loss.” “Bitter.”

Gore, a Democrat, gave his speech more than a month after the 2000 Election Day and after a historic U.S. Supreme Court ruling paved the path to victory for Republican George W. Bush amidst public confusion and outcry.

Stuart asked his students what they thought of Gore’s delivery and message.

“I think he was being sarcastic,” said one student. “Like you could tell he didn’t really believe what he was saying, and felt like he should have won, but he still called for unity and respect.”

As other students in the room nodded in agreement, Stuart said: “This is a hallmark of a free and fair election, that the person who lost, can get up there and offer a unifying message, even if he is bitter. Right?”

He noted that Harris was expected to give her concession speech later Wednesday. “I encourage you to watch it,” he told students. “See if she has the same message of unification and moving forward, even though you can guarantee she is feeling deeply about the loss.”

An election that turned on grocery prices and utility bills

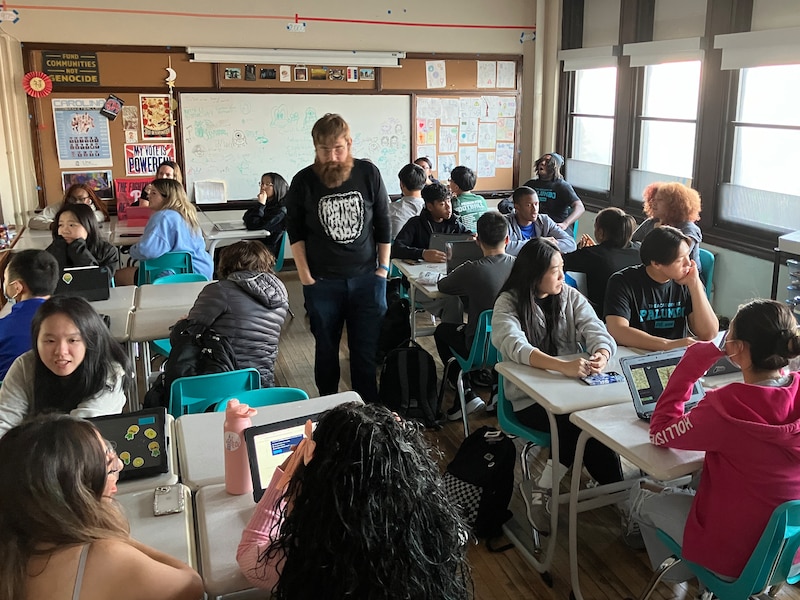

Philadelphia social studies teacher Charlie McGeehan prepared for every election outcome – but, he admitted to his students Wednesday morning, “this is not what I expected.”

When he went to bed Tuesday night before midnight, McGeehan had anticipated explaining to the juniors and seniors in his classes about how long vote counting can take. About how we might not know the outcome of the election for several days. About the role deep-blue Philadelphia would play in deciding the election.

By the time he woke on Wednesday, that plan was moot. So, he figured, let’s just give the students — many of whom had spent long hours working the polls the day prior — space to decompress.

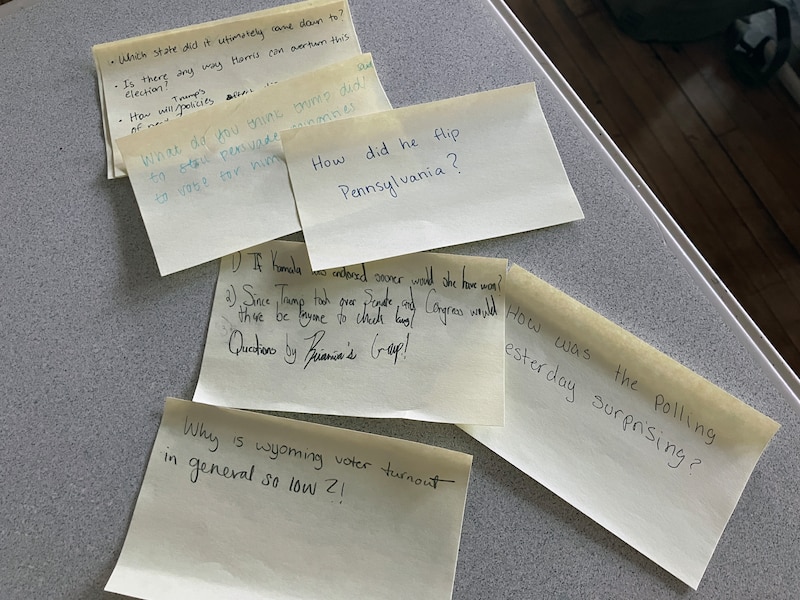

Together, they combed through the election results guided by students’ questions like “How was the polling yesterday so surprising?” “Which state did the race ultimately come down to?” and “Does Kamala Harris have any path to winning at all?”

To that last question, McGeehan was straightforward: “No, she doesn’t.”

Many of McGeehan’s students at the Academy at Palumbo are first- or second-generation Americans or immigrants. On notecards, students laid out their more personal fears, ones they didn’t necessarily want to share with the class.

“As a woman and a child of an immigrant, I’m honestly scared” read one. “I saw a post saying how Trump pledged to launch mass deportation… which makes me feel like not researching more because of how much more sick stuff I might read,” said another.

One said “I feel great because Trump’s [positions] align with what I want. Especially with the issues of censorship, grocery prices, and utility bills.”

‘Kind of a very depressing day’

Nehemiah Legrand tried to eat dinner Tuesday but couldn’t finish. She was glued to her phone. She was up until 3 a.m.

The 13-year-old student at Enlace Academy, a pre-K-8 school in the International Marketplace area of Indianapolis, is an American citizen by birth whose parents are legally living in the country. The family fled Haiti after her older brother was kidnapped in 2020 amid the country’s political turmoil.

Still, Trump’s campaign rhetoric around immigration scared Nehemiah – and made her fear that her family would be deported.

“I just feel like today — it doesn’t feel normal,” she said, sitting in the school’s hallway on Wednesday, looking out the window at the rain. “People are not talkative or none of that. It’s very, very strange. It’s kind of a very depressing day. Because everyone just doesn’t know what’s going to happen next, and you can tell everyone is stressed.”

The presidential election has loomed large over her and her classmates at the school, where many students come from Latin America and Haiti. At this school, students have to grow up fast. Many carry trauma from their immigration to the United States, said lead social worker Hailey Butchart.

Now, students like Nehemiah are preparing for what the next four years with Trump — whose platform includes deploying “the largest deportation operation in American history” — will mean for them.

“A lot of the students I speak with have had a family member that has been deported, and they live with that fear as well,” Butchart said.

The power of social media in elections

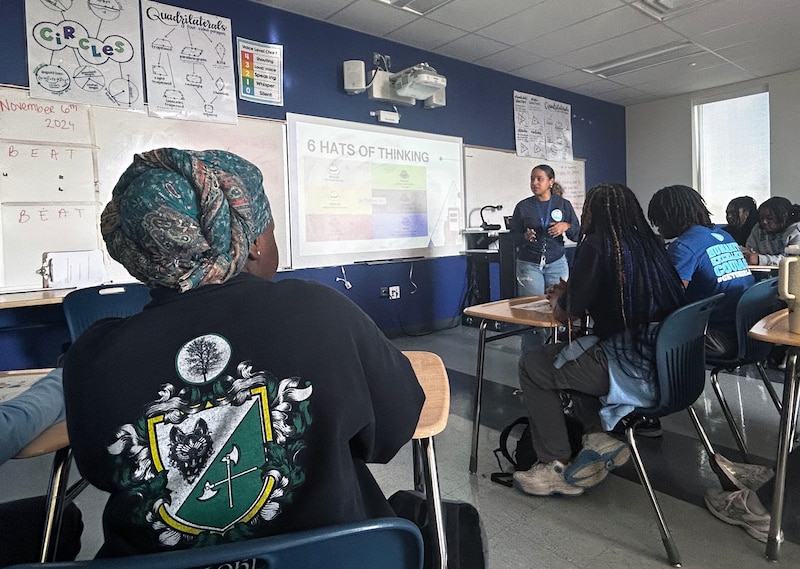

On the morning after Election Day, Zy’Asia Weathers rolled over in bed to grab her phone on a nearby nightstand and scrolled through TikTok.

But instead of seeing videos of makeup reviews or the latest trends, Zy’Asia’s feed was filled with women and girls crying about the outcome of Tuesday’s election and the potential impact on female reproductive rights.

“People were even saying, like, very vague things, like, just thinking the worst of the worst,” added Zy’Asia, 17, a senior at KIPP Newark Collegiate Academy.

Throughout the school day Wednesday, Zy’Asia and her peers talked about other videos they saw, like people celebrating former president Donald Trump’s reelection and others questioning what his victory would mean for the nation.

Zy’Asia is also the president of her school’s Student Government Association, and on Wednesday, the group met to discuss the presidential outcomes. Yanibel Feliz, the advisor of the group, walked students through an exercise to discuss the election process, the outcome, and the effect of social media.

Some students said they were shocked about Trump’s victory because they had seen much support for Harris on social media.

“Sometimes, social media might paint a picture of how elections will go,” said Trinity Douglas, a junior at the school, during class. “But it has a big effect on our generation.”

‘I’m afraid what will happen to my family’

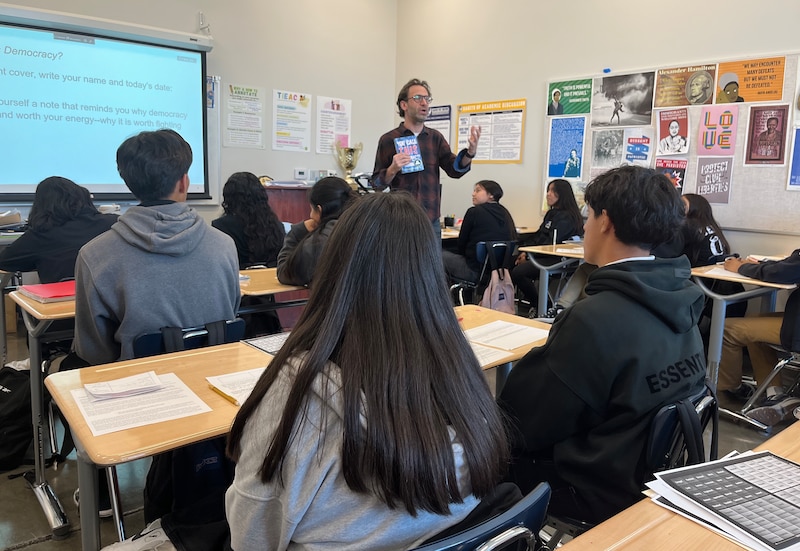

The icebreaker in Joel Snyder’s government classes on Wednesday was to respond to the prompt: “I am feeling … because …”

The responses were wide-ranging and included students who were enthusiastic about the election outcome and those who were disappointed the U.S. would not, after all, elect a woman as president.

In the few minutes they were given, students took pencil to paper and wrote that they were “shocked” to hear how well Trump did with Latinos, “furious” at what they saw as sexism in the results, and “concerned” that America had once again elected a man whose flaws and felony convictions are, by now, well known.

Some answers hit closer to home. “I am feeling uneasy,” one student wrote, “because I’m afraid what will happen to my family who are undocumented.”

Standing at the front of his class at Ánimo Pat Brown Charter High School in the Florence-Firestone neighborhood of South Los Angeles, the teacher reminded his students that whether or not they are U.S. citizens, they have “the duty to be the protectors of democracy and of each other.” Snyder teaches about 140 students across five government classes, including one AP course. Of the roughly 600 students enrolled at Ánimo Pat Brown, almost all of them are Hispanic — their families hailing from Mexico, Guatemala, and elsewhere in Latin America.

Snyder also asked his students to write down one issue that they care about and how they think Trump’s election might impact it. The students chose abortion rights, the economy, constitutional norms, and, again and again, immigration. They shared their fears of mass deportations and stories of family members who had waited years for green cards they may never get.

“My main concern is how, even despite being a citizen, I still won’t be protected because my parents are immigrants,” Natalie, 17, a student in Snyder’s AP U.S. Government and Politics class, told Chalkbeat.