Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

On the Saturday after the election, Cheryl Suydam headed to an impromptu meeting of parents of trans kids. The gathering was called by the local chapter of PFLAG, an advocacy group that supports LGBTQ+ people and their families, to discuss their feelings after American voters elected a president who ran on an openly anti-trans platform.

“Every single person in that room was absolutely terrified,” Suydam said.

Suydam and her husband are the parents of three daughters, including a 15-year-old who is transgender. They live in Asheville, North Carolina, a more progressive community in a state that is less so.

About two dozen parents seated around a living room discussed changing their children’s legal names while they still could, starting medical treatment while it was still available in other states, and moving to more welcoming communities.

“It was cathartic to connect with others living this same experience and feeling the need to mobilize in some way,” Suydam said.

President-elect Donald Trump has pledged to bar transgender athletes from competing in women’s and girls’ sports, ban gender-affirming care for minors, investigate whether such care should be available even to adults, roll back the Biden administration’s Title IX changes that gave transgenders students more legal protections at school, and punish schools that teach what Trump calls “left-wing gender insanity.”

“Teachers are wondering: What resources will I be able to use to keep kids safe? And that’s not just LGBTQ kids, but all students,” said Scott Miller, co-chair of the LGBTQ+ Caucus of the National Education Association.

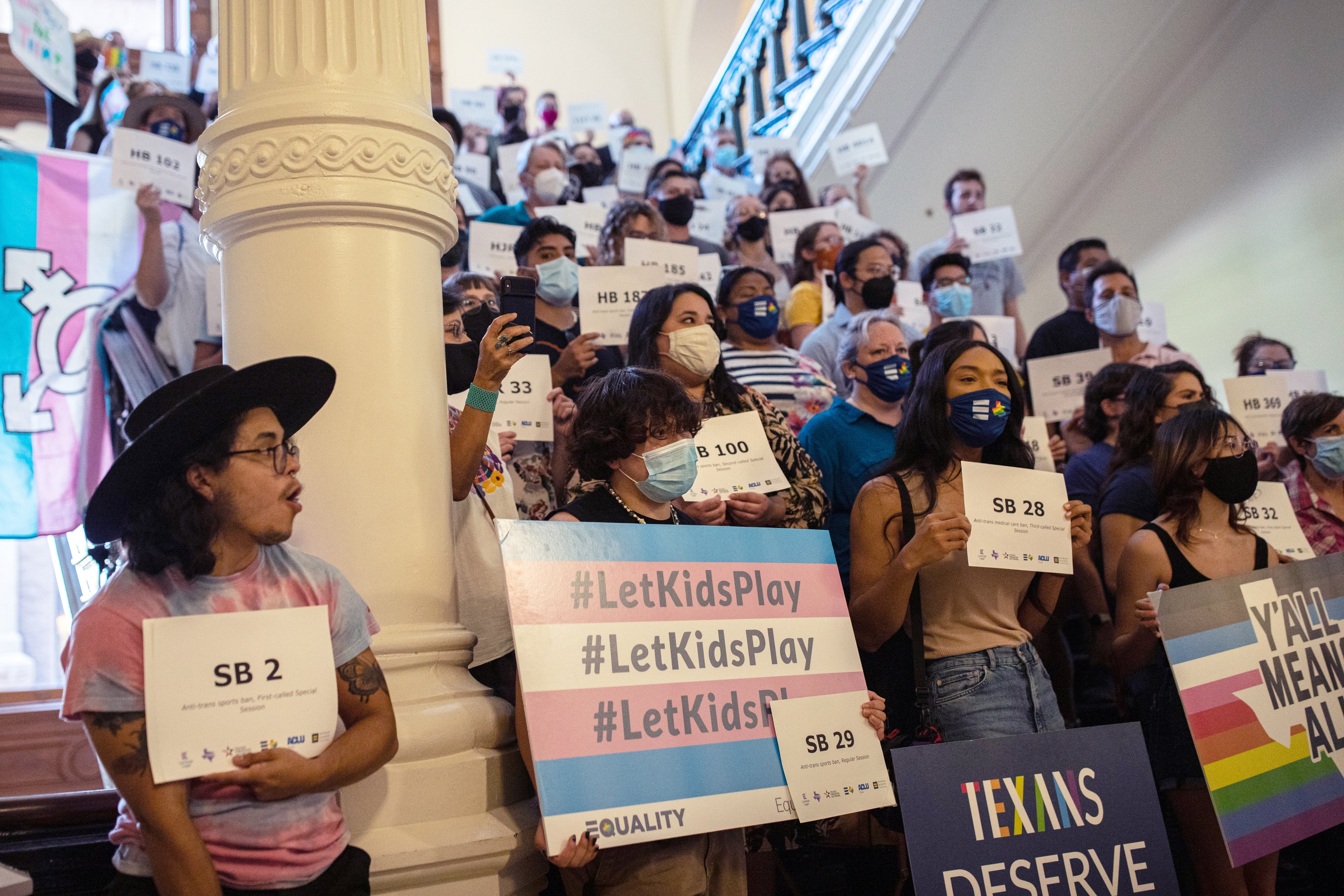

Students and teachers in Republican-led states that have passed anti-trans laws have experience resisting those laws, said Craig White, director of Supportive Schools at the Campaign for Southern Equality — and they have lessons for people in the rest of the country if the federal government pushes those policies into more states.

Many anti-LGBTQ+ policies are vague, leaving room for districts and teachers to take a more supportive approach and for students to keep exercising their free speech, White said. Activists are also contesting those laws in the courts.

Since Trump’s election, White said he has been overwhelmed with calls from people who want to organize.

“My weeks have not just been doom and gloom,” White said. “Within just a couple of days, I’ve seen people turning towards energy and activism and organizing. I have not even been able to keep up with the number of people contacting me and saying, ‘Okay, we’re ready to take action. What do we do now?’”

Students move to secure documents, treatment before inauguration

In Texas, Mandy Giles works supporting families of trans children. Since the election, she’s received many messages expressing fear and seeking advice.

“Parents of trans kids and young adults have been scared for a long time in Texas, but there has been a feeling that there was some level of federal protections that now may be going away,” Giles said.

She runs a monthly support group in Houston. The first meeting after the election had the most attendees ever — but at least half of the families in the meeting said they will be moving out of state soon.

“Some families have been with us since the beginning,” Giles said. “We had some tearful goodbyes because we knew we wouldn’t be seeing each other again before the end of the year.”

In North Carolina, Suydam has found support locally despite hostile state laws. The state has restricted discussions of gender and sexuality in elementary schools, banned gender-affirming care for minors, and barred transgender youth from competing in middle, high school, and college sports.

“It’s an incredible community,” Suydam said. “As soon as my daughter came out, we contacted the school, and they quickly started using her preferred pronouns and name.”

Her daughter, whose name she asked to withhold to protect her privacy, started hormonal therapies before state legislators passed a bill in 2023 to ban gender-affirming care to minors. The law allowed minors who already were under treatment to continue. But her daughter had to stop swimming after legislators passed a law that students can only join sports teams for the genders they were assigned at birth.

“She used to be a competitive swimmer and has only competed as a female,” Suydam said. “Since these laws were passed, she has stopped because they gave people the freedom to talk openly against trans athletes. So, it never felt safe to talk to her teammates or the parents of the teammates about the fact that she was trans.”

The family is preparing for the coming months. “I’m actively updating all of her documentation to reflect her name and gender now and in the next few weeks while I still can,” Suydam said.

Trump’s election means that any hopes of federal protection to counter state laws have disappeared. People are thinking about how they can protect themselves and their family members, advocates said.

Ben Cooper is an attorney based in Columbus, Ohio, who has provided free legal advice at a legal aid clinic for LGBTQ people since 2016. Since the election, he said he’s seen more people rushing to get their names and gender markers changed in legal documents.

This type of change is regulated by state law, but advocates fear the Trump administration may adopt policies that affect federally issued documents like passports.

“My advice is: If you’ve been thinking about adjusting your documents, then there’s no time like the present,” Cooper said.

Milo McBrayer, 17, who identifies as transmasculine and queer, is also considering fast-tracking his documents before Trump takes office.

“I am also thinking of going out of state to start gender-affirming care,” said Milo, who also lives in Asheville. “Because of North Carolina’s ban, I didn’t plan to do it before I turned 18, but now I don’t know if my ability will go away after Trump takes office.”

Milo said that he has also become more active in local groups that support trans people “as a way of building a stronger support system.”

One of those is the Pansy Collective, a group of LGBTQ+ artists, who recently organized a “bug-out bag” workshop. The workshop covered information about how to be safe and what to bring if you need to escape quickly, whether that’s fleeing a natural disaster such as Hurricane Helene or moving across state lines to access gender-affirming medical care.

“The workshop was mostly about reducing anxiety by providing educational resources,” said Riley, an organizer with the group who asked that his last name not be published.

Bullying a major concern for transgender youth

Last year, the Youth Risk Behavior Survey estimated that 40% of students who identify as transgender or who are questioning their gender identity suffered bullying at school. Advocates worry the election may exacerbate hostile environments in some schools.

According to the Movement Advancement Project, 25 states have no specific protection for LGBTQ+ students in their anti-bullying laws, and two states — Missouri and South Dakota – actively ban schools from including LGBTQ+ students in their anti-bullying policies.

Even in states such as North Carolina where students have some protections from bullying, ensuring that schools respect the law is not always easy.

“In my old school, people just had the audacity to yell slurs at you walking down the hallway,” said Milo, who transferred to a charter school for his senior year. “And even though I was being bullied pretty heavily, the school refused to do anything about it because it was about me being trans. And that has turned into a political issue, not a human rights issue.”

In his new school, The Franklin School of Innovation, he feels much more comfortable and has found community among other queer students.

Even in liberal states like California, trans students and their families can have difficulties. Juliet Stowers is an elementary school teacher in Orange County, California, and the parent of a 16-year-old trans girl. She said that it is not rare to hear anti-trans rhetoric in her district, and many parents complain about the presence of trans kids in schools.

“Some days, it can be debilitating,” she said. “Trump is saying that we, as teachers, are offering hormones or performing surgeries when we have to pay for the pencils in our classrooms.”

Stowers said she’ll continue working in the community to support other educators, parents, and kids.

“My daughter is terrified, but I’ve been telling her, ‘Don’t worry, there are many people ready to fight. We are ready to fight,’” she said.

Across the country, Milo feels similarly.

“I felt very failed by the adults in my country,” he said of the election results. “So, I have been spending a lot of time grieving. But I have also been trying to do a lot of community work by helping my friends as much as I can, sharing resources to cope with this situation, and talking about it openly.”

Wellington Soares is Chalkbeat’s national education reporting intern based in New York City. Contact Wellington at wsoares@chalkbeat.org.