Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

Having pledged to get rid of the U.S. Department of Education and get “woke” out of public schools, Donald Trump is returning to office. The coming year could start to reveal what these promises mean for American schools that face significant challenges, including looming building closures, stagnant student learning, and big questions about the very purpose of education.

Here are some of the education stories we’re watching in 2025.

What a Trump presidency means for schools

President-elect Donald Trump had some strong words for American schools on the campaign trail. He promised to get rid of the U.S. Department of Education and “send education back to the states.” He also promised to get the “woke” out of public education, an endeavor that presumably would require some bureaucracy to oversee American schools.

With Trump returning to the White House, the big questions are whether he’ll follow through on campaign pledges — and whether American students will feel the difference in their classrooms.

Most observers think actually abolishing the U.S. Department of Education is unlikely. It would require an act of Congress, and there’s probably not enough votes. But the idea does seem to have more traction than in the past, and a bill that would reassign many functions to other departments — as envisioned in the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 — was recently filed by a GOP senator.

The Trump administration could also cut funding for or eliminate certain programs, and replace career bureaucrats with political appointees, all without getting rid of the department. Civil rights enforcement could also look very different.

Some Republican state leaders have hailed the prospect of getting rid of red tape associated with federal compliance. They envision keeping similar levels of federal funding but with fewer requirements around how to spend it.

Trump has also promised to roll back new Title IX regulations that treat discrimination against transgender studnets as a form of sex discrimination. Conservative parent groups and Republican attorneys general have already sued to block the new rules, which LGBTQ advocates saw as providing some protection against hostile state laws. Some conservatives want these cases to still go to the Supreme Court in hopes the court finds gender identity is not protected under laws barring sex discrimination.

Increased immigration enforcement also is likely to have big ripple effects in schools. Reports indicate Trump may do away with the sensitive locations policy that limited immigration enforcement in schools, hospitals, and churches. Widespread deportations could leave traumatized children behind. School leaders and advocates are trying to balance the reality that they may not be able to protect all students with the desire to keep schools a safe and welcoming place.

School closures are increasing, but not everywhere

Faced with declining student populations, higher staffing costs, and the end of federal pandemic relief money, districts around the country are closing schools — or doing serious fiscal gymnastics to avoid it.

The latest data from the National Center for Education Statistics from 2023 shows school enrollment holding nearly steady from the year before, but still down 2.5% from pre-pandemic levels. Notably, while high school enrollment has stabilized, elementary enrollment is down, suggesting there’s no big rebound on the horizon. The ratings agency Moody’s gives American K-12 schools a grim financial outlook for 2025 due to falling enrollment and lower revenues.

Declining birth rates, gentrification, high housing prices, and more families opting for private school and home schooling have all played a role. In many cases, these trends were evident before the pandemic, but school districts used federal COVID relief dollars to shore up budget holes. In some cases they also added staff and raised teacher pay, exacerbating the fiscal crunch to come.

Already, leaders in cities like Denver, Columbus, Ohio, and Rochester, New York have voted to close schools. Philadelphia and Memphis are making plans to do the same.

The case of P.S. 25 in Brooklyn, New York, illustrates the problem. New York City spends $45,420 per child to keep the 52-student school open, yet it struggles to afford art, music, or after-school programming.

But these decisions are often wrenching and face pushback from parents and teachers. Citing lack of community support, Boston put its school closure plans on hold. So did San Francisco — and the superintendent resigned. The Chicago school board put a moratorium on school closures through 2027, even as fiscal pressures are driving a leadership crisis there.

With school closures come questions of equity and fairness. In many cities, the schools with the lowest enrollment serve mostly students of color. But keeping those schools open might mean students don’t have the same resources as their peers in other neighborhoods. Some advocates have called for closing low-performing schools to give students a shot at a better education. That approach harkens back to education reform policies that have largely fallen out of favor.

Many school districts are also trying to limit layoffs, which could reduce the savings they see from school closures. Districts are also trying to find ways to maintain tutoring and counseling programs they started during the pandemic.

NAEP could add to discouraging post-pandemic scores

Results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, are expected in early 2025. The tests were given in spring 2024 and will provide insight into the state of student learning four years after COVID school closures.

The results are much anticipated after a series of tests, studies, and analyses have painted a conflicting but often discouraging picture of student recovery. Most recently, a major international test showed that U.S. students’ math scores plummeted, with the declines concentrated among lower performing students. This widening gap between high- and low-performing students was present before the pandemic and raises major concerns.

Similarly, state and local test results show gaps based on income, race, and ethnicity. A major analysis released in 2024 found that students on average had recovered to close to pre-pandemic levels, a surprising outcome, but that analysis also found that academic inequality was growing.

Meanwhile, students who weren’t even in school when COVID started are showing delays, as are older students who saw critical learning years disrupted.

The big question going forward is: What are we going to do about the state of student learning?

Statewide efforts to improve math and reading instruction continue to gather steam, but for better or for worse, schools with low test scores don’t face many consequences. The research on aggressive school turnaround efforts is decidedly mixed. Democrats have largely backed away from test-based accountability, and Republicans are more focused on expanding school choice.

How states and Congress could expand school choice

Private school choice has exploded in recent years, with a dozen states now running universal or near-universal voucher or education savings accounts programs that give parents money to send their children to private school or educate them at home.

Trump’s election could give these efforts a boost. He’s promised to expand school choice, and Republicans in Congress are making another push on a federal tax-credit scholarship proposal championed by former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos that could make billions available, including in Democratic states that have been hostile to vouchers and education savings accounts.

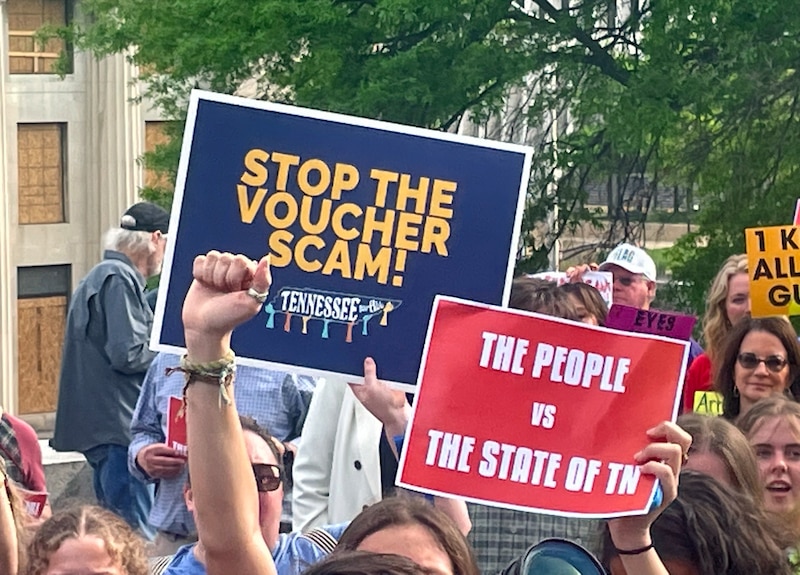

At the state level, many anti-voucher Republicans who had teamed up with Democrats to block private school choice lost their primaries as outside money poured into obscure legislative races. Now pro-school choice governors and lawmakers are making new pushes in Texas, Tennessee, Idaho, and elsewhere.

These coalitions could still fracture. A major voucher expansion seemed inevitable in Tennessee this year until disagreements over testing requirements and funding sank the deal. Now Republicans say they’re united and determined to expand them.

The meaning of high school is changing

Education advocates for years focused on getting more students to and through college. We still haven’t solved that problem, but a lot of the shine has come off “college for all.” Student debt concerns loom large, and there are widespread labor shortages in the trades. Policymakers are pushing for more career-connected learning, which is also being touted as a way to fight disengagement.

At the same time, states are ditching exit exams. This year Massachusetts voters overturned a requirement that students pass a standardized test to graduate high school, and New York decided to get rid of the Regents Exam starting in the 2027-28 school year. New Jersey — one of just six states to still have an exit exam — continues to debate whether it should keep it.

All of this is fueling a conversation about the meaning of high school, one that’s resurfaced periodically since the high school movement in the first half of the 20th century led to a dramatic expansion of secondary education.

That played out in Indiana this year with the adoption of a new high school diploma. An initial proposal called for significant work requirements to reflect that fewer Indiana students are attending college. To satisfy critics who said work requirements would make it harder for Indiana high school graduates to pursue college aspirations, the state ultimately settled on a diploma that offers multiple pathways.

Other states, such as Colorado, are developing programs that incorporate apprenticeships and internships alongside classroom learning.

But limited data makes it hard to know if career education is delivering the desired outcomes.

Erica Meltzer is Chalkbeat’s national editor based in Colorado. Contact Erica at emeltzer@chalkbeat.org.