Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

When Amber Faris was studying to be a journalist, a visit to a high school classroom for a college assignment prompted a pivot. She became an English teacher instead.

“This is the energy that I am looking for,” Faris recalls thinking to herself as she observed the class. “I always felt very passionate about journalism and speaking truth to power. But I was like: I could do that with young people.”

After two decades of teaching, Faris switched it up again last year, this time to become the library media specialist at her Lexington, Kentucky, high school, which is part of Fayette County Public Schools.

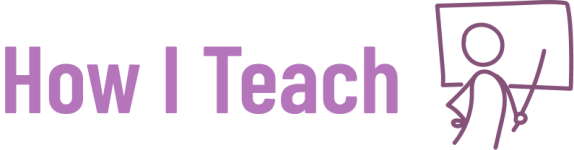

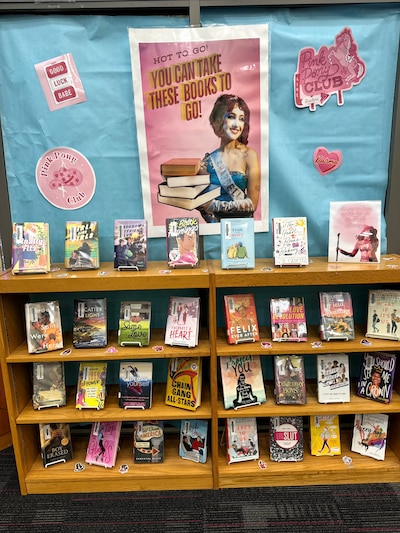

Now Faris is recommending books on Dunbar High School’s morning news, hosting reading challenges for students and staff — like last year’s 24 for 2024 — and crafting elaborate displays to entice teens to check out new titles. In recent months, that’s included an homage to the singer Chappell Roan and a collection of banned books draped in yellow caution tape.

Her community hasn’t seen the kinds of book challenges happening elsewhere in Kentucky, but Faris keeps tabs on them in case she ever needs to defend her catalog.

“That’s the hill I’ll die on,’” she said. “I’m a huge supporter of: We have to have books to support all of our children’s identities and perspectives. It builds empathy, it builds character. … This library is seen as the safe space, and I want to keep it that way.”

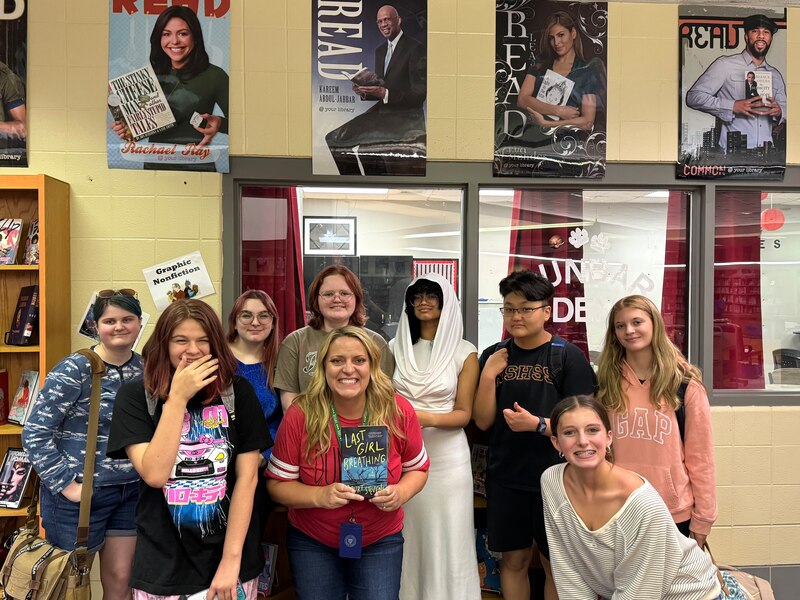

Faris has also been the sponsor of Dunbar’s Gay-Straight Alliance, or GSA, for nearly two decades, a position that gives her insight into how support for LGBTQ students in Kentucky has improved — and come under fire.

Her district, for example, is working to make sure each high school and middle school has its own GSA, and GSAs get funding so they can pay for activities like guest speakers and field trips. GSA sponsors meet monthly, and there’s a district official who oversees LGBTQ equity issues.

“Having people at your district show up and say: ‘This is the right thing to do,’” really matters, Faris said.

But there are limits. Last school year, when LGBTQ high schoolers tried to gather to voice how their schools could better protect them from harassment and discrimination, the district canceled the forum. That was likely due to a 2023 Kentucky law that prohibits instruction and presentations about gender identity and sexual orientation.

Instead, students attended a voluntary event with their parents’ permission. It was hosted at Dunbar. At the time, Faris told her school’s student newspaper she felt like “our LGBTQ+ students are just kind of being brushed aside and treated like second-class citizens.”

Chalkbeat talked with Faris over the course of two interviews — one in mid-November and another in mid-December — about how the students in her school’s GSA are responding to Donald Trump’s reelection, how she helps teens figure out what they might want to read, and what’s on her holiday reading list.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you make the switch from teaching English to being a school librarian?

The library had always been my place. It was just kind of a natural progression.

I love doing research. I’ve always, even with my freshman, taught [students] how to do a database search, how to cite, and how to back up your thesis with evidence. I knew that that was really transferable to the library.

I’ve always been a massive proponent of reading for pleasure and trying to read what high school students read. I read between 125 and 150 books a year. I had outside reading as a part of my class. I don’t care what it is. We would read together, every day, for 15 minutes, and I would read with them.

I always tell people: Scroll less, read more.

How do you approach student requests for book recommendations?

I do a lot of what I call ‘five-minute manias’ with them. [Those are] like book tastings. I put out a bunch of different books from a bunch of different genres and authors. I’ll just have them grab a book that looks interesting and read the title. Does that look interesting? Okay, read the back cover. Do you still like it? Okay, read the inside cover. Read the first sentence, and then have them share why they either liked it or they didn’t. And then have them read the first page.

A lot of times, that’s all they needed to know that that was something that they could actually get into, which helps them find books.

How are students in your GSA responding to Trump’s reelection? How are you helping staff to support LGBTQ students?

The day after the election, I did a: ‘Hey, I know some of you all may be feeling not so great, so I’m here if you want to talk about it.’ They were all just so happy to have that space.

I just let them vent. Of course, there’s a lot of venting about not feeling safe. We have some kids at our school that are trans, that are definitely wondering how their health care is going to move forward or if it’s going to be stalled.

There’s a lot of fear and frustration. But we have each other. They know they have people at school who care about them.

Part of my job is to make sure that everybody in our school is thinking about the LGBTQ kids and how we can help them. I sent an email [the week after the election] about being aware that this can be really hard for these kids, and to watch out for them, because they’re already at such a high [risk] for suicide and depression.

I shared an article from The Washington Post about how calls to crisis lines [from LGBTQ youth] were up like 700% [after the presidential election]. I’m just reminding people: We have a GSA, it’s Mondays after school, they can contact me. And I reiterated at GSA that we have two mental health specialists. I’m like: It’s okay to go talk to your therapist or the mental health specialist about your feelings, because your feelings are valid, and I know you’re afraid, and that’s okay.

It’s hard in a district like ours, where we definitely live in a pretty blue dot in a red state. A few of them may live in purple neighborhoods, but for the most part, we’re pretty accepting. We’re a college town. They know that they have options to go to colleges that have accepting housing and programs.

I have not heard them say anything just yet like: ‘We want to do X [in response to the election].’ But I feel like the younger ones, it’s been more of: ‘I can’t wait to vote. I can’t wait to be able to have my voice heard.’

What are some of your favorite books to introduce students to and why?

This is a holiday one that I’ve recommended, and it’s called “Finding My Elf.” It’s by David Valdes. It’s a male-to-male queer book.

It’s [about] a high school kid who went to NYU to be the theater major and has come home from college, and is just flunking out. Small-town kid that thinks New York is gonna change them, and then they’re just floundering. And they’re trying to tell their single dad that things aren’t going well, and they might lose their scholarship. Then he gets this job as an elf — if you imagine like Santaland Diaries.

It’s definitely kind of an enemies-to-lovers, not-everything-is-what-it-seems [story]. I love how it dealt with mental health and expectations of your parents and first-generation [college-going] type stuff.

We want to spread Black joy and queer joy. And yes, there’s tons of books out there that have awful things happening in them that kids need to read, too. But books like what I’m talking about: It’s an easy read, it’s short, but it’s funny, and it’s sweet, and it deals with realistic issues in a meaningful way without it being cheesy. Those are the types of books that I’m looking for.

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.