Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

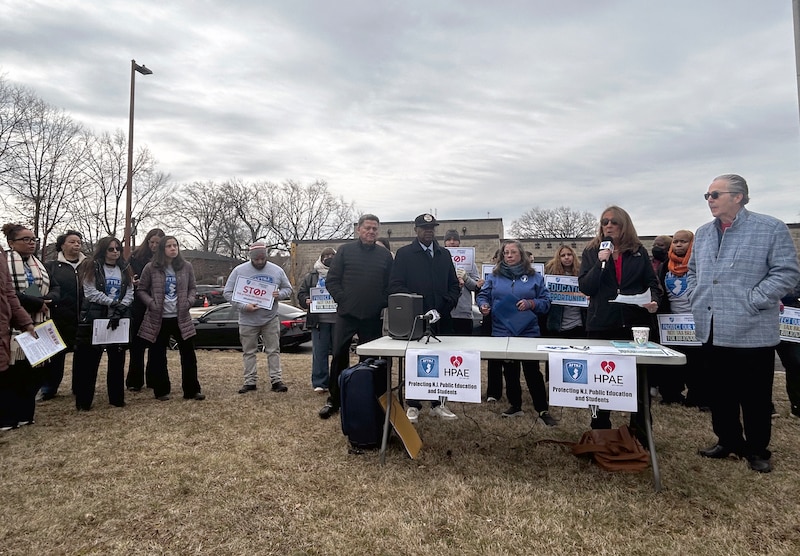

On a cloudy, cold Tuesday morning, a cluster of teachers and community activists in Newark chanted “Stop the cuts!” as they stood in their coats outside an elementary school that serves the district’s students with disabilities.

In a Philadelphia school auditorium, teachers, district officials, and lawmakers faced more than a dozen students with disabilities and promised to protect the educational services those students rely on.

In Chicago, the rain came down as more than 20 union members stood in front of Minnie Miñoso Academy elementary to join educators across the country to rally support for public schools and urge lawmakers not to cut federal funding.

The rallies on Tuesday were part of a national effort led by the American Federation of Teachers to protest threats to cut federal funding for education. The “Protect Our Kids” day of action came as newly-installed Education Secretary Linda McMahon prepares to overhaul the federal education department and shift how the agency operates.

McMahon, sworn into office a day before, promised senators at her confirmation hearing that key funding streams, such as for students with disabilities, won’t be harmed. But many advocates fear plans to upend the education department could affect federal support for low-income students, students with disabilities, first-generation college students, and other vulnerable groups.

Republican budget proposals already call for significant cuts to school meals programs and to programs overseen by the House Energy and Commerce Committee, which include Medicaid. Those are important sources of money for public schools. And public education supporters fear even steeper reductions in education spending as Republicans look for ways to pay for President Donald Trump’s tax cuts.

“The millions of children and young adults who get funding to help them in literacy, to help them with occupational therapy and physical therapy, to help them go to college, to help them with hands-on learning — that’s what the federal government spends this money for,” said AFT President Randi Weingarten in a virtual press conference. “It goes directly to schools for these kinds of services.”

Across the country, in small towns and big cities, thousands of educators donned “Red for Ed” shirts and held walk-ins at their schools — and posted on social media using the hashtag #ProtectOurKids — to explain how taxpayer money funds necessary educational services.

Public schools are governed by local school boards and primarily supported by local property taxes and other state revenues. The federal government provides funding and support for school lunch programs, students with disabilities, homeless students, those from low-income families, and students learning English.

Newark schools receive roughly $80 million in federal funding, about 10% of the district’s annual budget. Philly schools receive more than $500 million in federal support, roughly 10% of that district’s budget, while Chicago Public Schools receives $1.3 billion, about 16% of its budget.

Newark at risk of losing pipeline of student teachers

In Newark, city and school leaders joined educators and student teachers outside New Jersey Regional Day School, one of five specialized schools that serve students with disabilities in the Newark Public Schools district.

Beck Akinyemi, a student teacher pursuing their teaching certification at Montclair State University, stood alongside peers and held up a sign that read “stop the attack on education.” Akinyemi is part of the latest cohort of students supported by the Teacher Quality Partnership grant, a federal grant program that helps prepare teachers for high-need schools and subject areas through a teacher residency with partner school districts.

But Akinyemi is at risk of not completing the program after the federal education department canceled the grant at Montclair State in February. Partner districts of the program, such as Newark Public Schools, could lose their pipeline of qualified teachers due to the cuts.

“Not only will this affect all the necessary social roles schools play in our communities, they will affect the future of the next generation of educators,” Akinyemi said.

Newark Mayor Ras Baraka called the threats of federal funding cuts an attack on public school education and working class families.

“We need to do what we can to support the folks here, the organizations here, and make sure the funding remains solid and stationary,” Baraka said in front of a small crowd of educators, student teachers, and union members who chanted “stop the cuts” after his speech.

New Jersey receives around $1 billion in federal funding every year for education, and about half of that money is used for programs serving students with disabilities under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Of the $1 billion, New Jersey receives over $460 million in IDEA funding, according to the Education Law Center. This school year, Newark received $66 million in special education aid from the state, according to the district’s latest budget.

Last week, the Newark Board of Education joined school boards nationwide, including Philadelphia, in passing a resolution to formally oppose the Republican congressional budget proposals and Trump administration threats to education funding more broadly.

In Philadelphia, special education cuts would be ‘catastrophic,’ leaders say

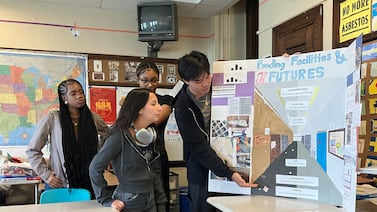

As part of Tuesday’s nationwide protests, Philly educators, city officials, and district representatives rallied at Widener Memorial School – the only public school in Pennsylvania that exclusively serves students with disabilities and diverse learners.

Widener student Taisha Cruz, who uses a wheelchair, said her school and the funding it receives “gives us a sense of freedom you will never understand.”

At the rally, the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers union described in detail what city students would lose if IDEA funds were cut.

Acting Pennsylvania Secretary of Education Carrie Rowe has said deep cuts to education programs “would be nothing short of catastrophic” and “would cause irreparable harm,” to all students, especially those students with disabilities.

According to the PFT, Philly schools receive $178 million in Title I funding, $56 million in special education funds, $7 million for career and technical education programs, and $86 million for school meal reimbursements in addition to federal grants for school facilities, prekindergarten programs, and more.

Funding cuts could threaten the very existence of Widener, which relies on federal funds to support small class sizes, paraprofessionals and teacher aides, physical and occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, and activities including wheelchair basketball.

“All of this would not be possible without the funding that comes from IDEA,” said Widener principal Theresa Harrington.

A sign in the school’s lobby showed upcoming student trips to the zoo, the city’s flower show, and dress-up days for “superheroes vs villains” and “mismatch day.”

Several city and state officeholders warned funding cuts would cause a crisis in Philly schools likely to be felt for years.

“I never thought the day would come when we would look at the possibility of education being dismantled from the federal level,” said City Councilmember Isaiah Thomas, chair of the education committee.“This will have an impact on generations to come.”

Chicago teachers want contract to protect schools from federal ‘foolery’

Those messages were echoed in Chicago where Chicago Teachers Union leaders and members joined the AFT campaign while also rallying around its remaining contract demands. As McMahon moves to make drastic changes to the way the federal education department runs, the clock is ticking toward a possible strike in the country’s fourth largest school district.

Standing in the rain outside Minnie Miñoso Academy Tuesday morning, CTU President Stacy Davis Gates said the union’s contract fight is aimed at “fortifying our school communities against the encroachment of the federal government and its foolery.”

“To sit here and say that special education services are not needed, that Title I is not needed, is an affront to all the sacrifice that’s been made to create this institution called public education,” said Jitu Brown, a recently-elected Chicago school board member and longtime activist who has organized marches in Washington, D.C. with the national Journey for Justice Alliance.

Chicago is shifting away from a school system under mayoral control to one governed by elected representatives. The current partially-elected, 21-member board is grappling with budget challenges now that federal COVID relief money has disappeared.

“Now is not the time to mourn. Now is the time to organize,” Brown said. “They may run D.C., but they don’t run Chicago.”

Dale Mezzacappa contributed to this story.

Carly Sitrin is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Philadelphia. Contact Carly at csitrin@chalkbeat.org.

Becky Vevea is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Chicago. Contact Becky at bvevea@chalkbeat.org.

Jessie Gómez is a reporter for Chalkbeat Newark, covering public education in the city. Contact Jessie at jgomez@chalkbeat.org.

Catherine Carrera is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Newark. Contact Catherine at ccarrera@chalkbeat.org.