During the seven years I served on the Derry School Board in New Hampshire, the board often came first. During those last two years during COVID, when I was chair, that meant choosing many late-night meetings over dinner with my family. It meant working my day job on weekends to make up for frequent board-related meetings and calls during the week. Once, it even meant walking out of my daughter’s ninja meet to take an urgent call from the superintendent.

These efforts were often met with anger from community members, who accused the board of not listening to them — by which they seemed to mean not agreeing with them — and making decisions that hurt kids. Parents who supported us rarely came to meetings, but they did send emails; people who were angry sent emails and came to meetings.

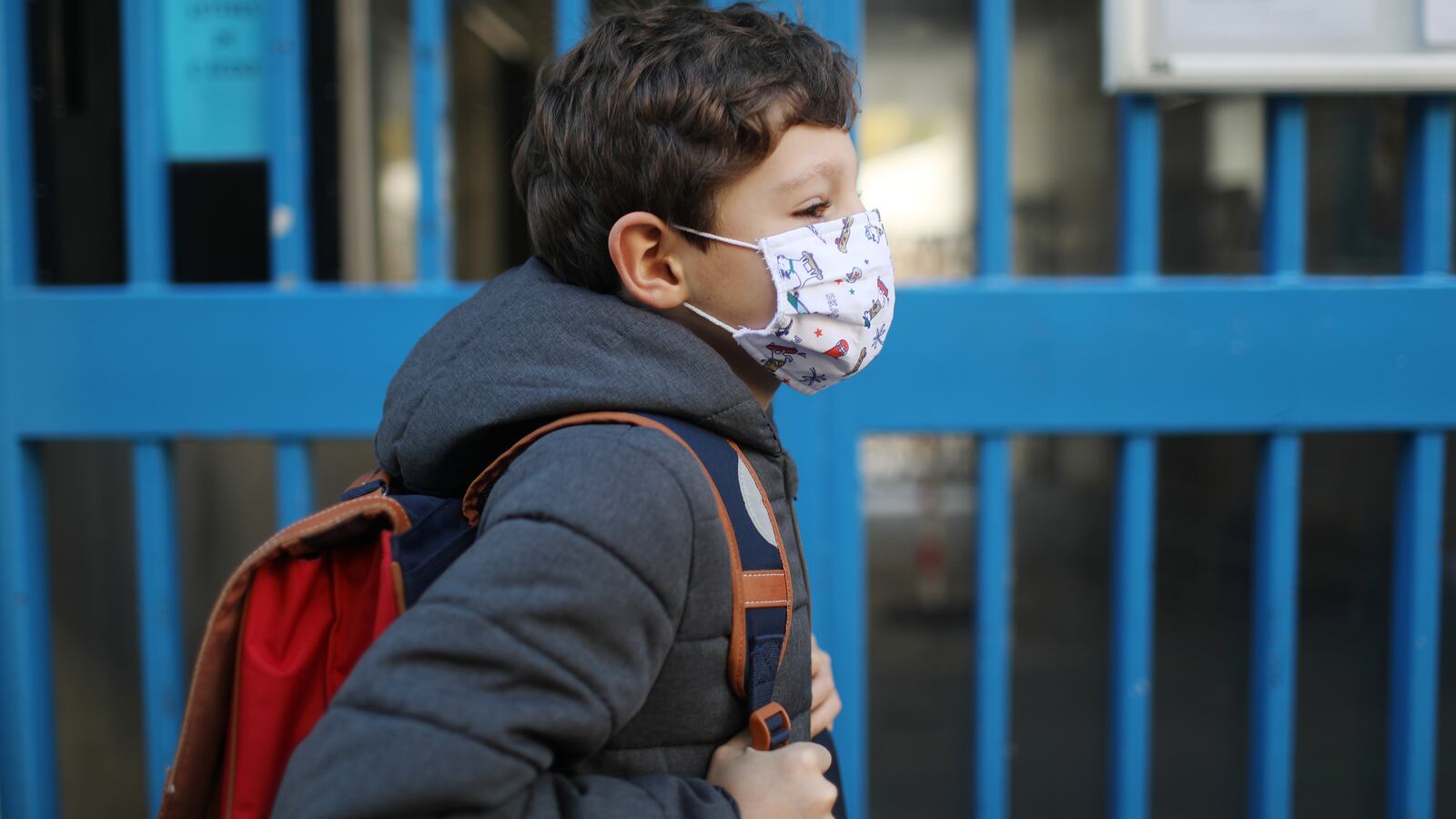

They were upset when we voted to require masks in schools during the height of COVID, when we, like school districts across the country, temporarily transitioned schools to remote learning, and when we refused to ban certain books from school libraries.

There are two sides to every story, but they can only be heard when people practice civility. Many parents honestly believed that masks and distancing rules were having a negative impact on their children’s social and emotional well-being, as well as their ability to learn. Their concerns weren’t the problem; it was how they expressed them, often using demeaning language, calling us “selfish” and “idiots.”

During the pandemic, which coincided with a national racial reckoning following the 2020 murder of George Floyd, members of the public threatened us, called the board Nazis, and claimed students in our K-8 district were taught to feel guilty because they are white.

Our board meetings were open to the public, and they were often tense and raucous. Audience members often clapped when they agreed with a speaker and sometimes yelled over someone with whom they disagreed. At times, we paid police to attend meetings in case the outbursts got out of control. I always responded to people with great care, knowing my words could be chopped up and posted online in a way that did not convey their original meaning.

With one year left on my term, I stepped down in 2023 and let the community choose someone else to serve out my term. But the anger about mask mandates, remote schooling, and district vaccine policies created a distrust that still cast a shadow on the board’s decisions.

Students continue to pay the price. Last year, for the first time since my kids entered Derry schools, the budget, which was put to a townwide vote, failed, leaving a nearly $1 million hole. Everything else failed, too, including a proposal to close two older school buildings and build one new one, and another to fix existing buildings. The voters were clear: They didn’t trust the board with their money.

Since resigning from the board, I haven’t attended board meetings for mental health reasons. But I attended the meeting the month after the March 2024 vote. My kids would both be at the regional high school, which the town pays tuition for by contract, but I was curious how the district planned to close this gap in the lower grades.

At the meeting, I received Excel handouts that laid out options based on whether all schools stayed open or whether one district school closed. The biggest-ticket options were all bad and included cutting a beloved gifted and talented program, eliminating math teachers, and increasing class sizes to state maximums.

Other suggestions included putting off replacing staff laptops, combining bus routes, and forcing more kids to walk to school. But those options alone were unlikely to close the budget gap. Scanning the crowd, everyone seemed displeased. And who could blame them? Still, I’m not sure what people expected with a $1 million shortfall.

At the start of the meeting, I had a knot in my stomach. I was worried someone would recognize me and approach me. As a board member I had absorbed so much anger and mostly held my cool, but it wound me up and sometimes led me to yell at my family. This was not the kind of person I wanted to be and was no longer the person I was. Then I took a deep breath and reminded myself the main responsibility was no longer on my shoulders.

Come March 2025, the town voted again for a bond to repair the schools. This bond was smaller than the previous one, but it passed overwhelmingly. Apparently, a year with a tight budget and no school repairs caused enough pain to drive more parents to the polls. But the fight also exhausted board members, with several of them opting not to run for reelection.

At its most basic level, the second law of thermodynamics states that entropy, or disorder, is the natural state of the universe and increases over time. To create order requires energy. After seven years on the board, my energy was needed elsewhere. However, I have learned that hostility increases disorder, which requires even more energy to reverse.

Hopefully, there will be more board stability, and school buildings will be fixed quickly this coming year; if not, it’s the students who will pay the price.

Erika Alison Cohen served seven years on the Derry School Board, the last two as chair. Her two teenage children are in high school. Erika works as a writer, ghostwriter, and editor, helping executives write and edit books.