Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

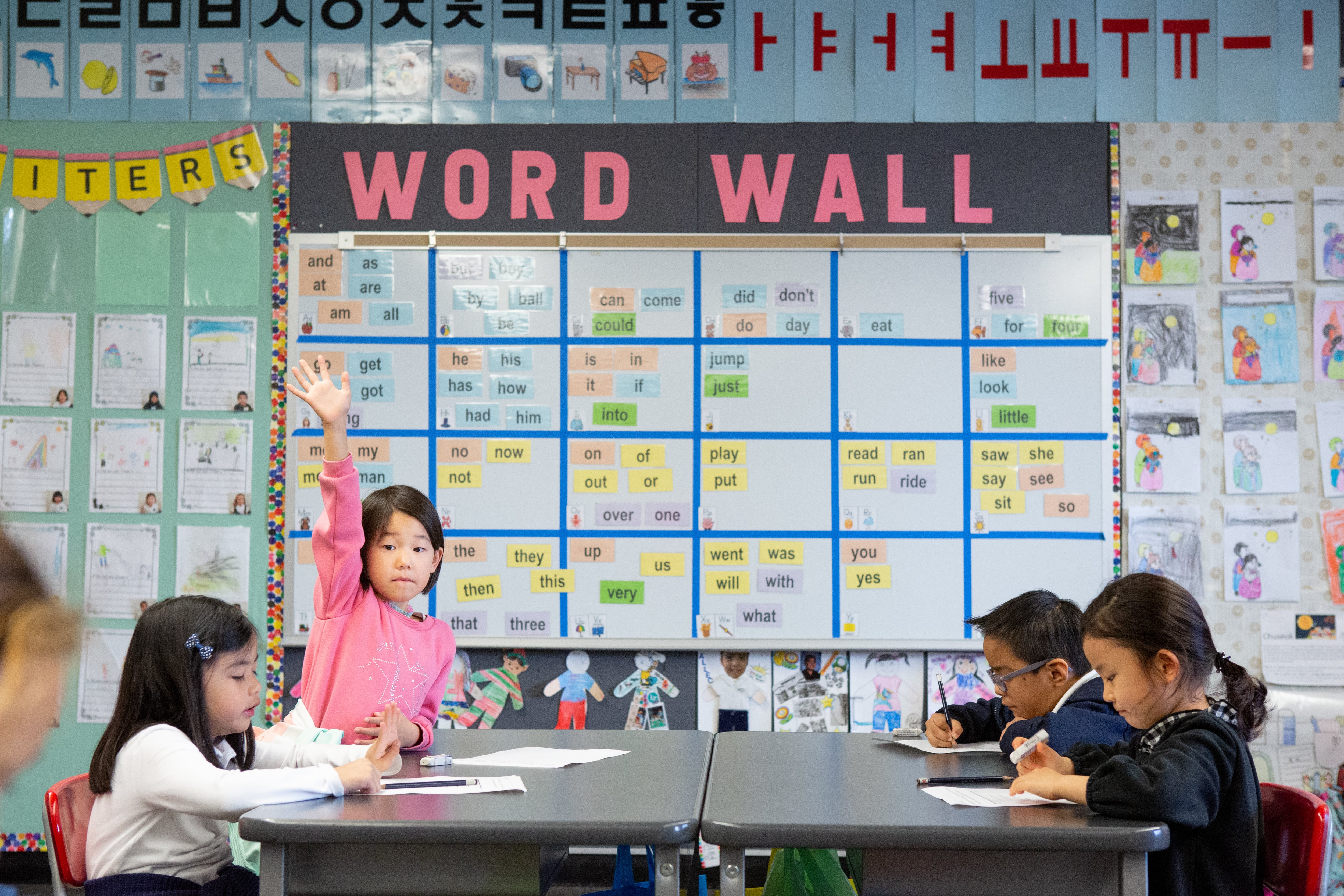

President Donald Trump has declared English the official language of the United States.

But his administration has fired nearly every Education Department staffer who ensured states and schools properly spent the hundreds of millions of dollars earmarked to help over 5 million students learning English.

It appears that just one staffer remains from the Office of English Language Acquisition, or OELA, after the Trump administration announced last week it would cut the Education Department staff in half.

“Your organizational unit is being abolished along with all positions within the unit – including yours,” an official with the department’s human resources team told the laid-off OELA staffers in a March 12 email.

Two days later, an administration official told state officials that the department’s Office of Elementary and Secondary Education would take over the OELA.

Advocates for English learners and outgoing Education Department staffers worry the deep cuts to OELA will have serious effects on students, families, and school staff. Without a dedicated office to keep an eye on spending, they fear federal dollars won’t reach the English learners they’re intended to serve, and that the quality of teacher training will suffer.

“There won’t be any more staff to provide guardrails on the federal funding,” said one laid-off OELA staffer who spoke with Chalkbeat on the condition of anonymity because they fear retaliation from the Trump administration. “Ultimately, it will affect the quality of education that English learners get across the nation.”

Among those expressing concerns is an official who led the OELA — and helped maintain it as a standalone office — during Trump’s first term.

Adding to the uncertainty is Trump’s executive order that he said will close the Education Department. The president said Thursday before he signed the order that the federal government will preserve high-profile programs at the department, but did not mention its office for English learners.

OELA staff have played a key role in monitoring how states and schools spend $890 million in federal Title III funds, which are allocated based on the number of newly arrived immigrant children and students learning English. When states and schools have questions about whether they can use their money on a certain after-school program or a new family liaison role, OELA staff track down the answers.

The office supports dozens of universities, nonprofits, and others who train bilingual education teachers. It oversees a grant program that helps Native American and Alaska Native children learn English alongside indigenous languages.

And the staff maintain the National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition, a hub for data, research, and best practices that many schools rely on. Some resources, like a recently released dual language playbook, take over a year to produce.

OELA had 15 staffers in January, according to a staff list posted on the Education Department’s website. The team already had more work than it could handle before the mass layoffs, said Montserrat Garibay, who led OELA during the Biden administration and left her role as the assistant deputy secretary shortly before Trump took office.

“They were overworked,” Garibay said. “It was almost impossible to keep up.”

Hayley Sanon, the acting assistant secretary for the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, told state education officials in a March 14 letter that her office would manage Title III funds for English learners, as it did prior to December 2023.

She also said formula funding under the nation’s main federal education law, which includes money for English learners, “will continue to flow normally, and program functions will not be disrupted.”

“The Department is committed to fulfilling its statutory obligation to prepare English learners attain (sic) English proficiency and develop high levels of academic achievement in English,” wrote Sanon, who is also the principal deputy assistant secretary at the department.

In response to questions from Chalkbeat, Madi Biedermann, the Education Department’s deputy assistant secretary for communications, reiterated that Title III and OELA would now fall under the elementary and secondary education office. But Biedermann did not respond to questions about why or how many OELA staff are left.

Students learning English have often been denied help

In addition to decimating the English language acquisition office, the Trump administration has eliminated nearly 200 civil rights attorneys who would make sure school districts meet their legal obligations to support English learners.

Some see the elimination of staff who oversee Title III as a precursor to bundling up that money in block grants that states could spend with fewer restrictions. Several Republican governors have championed that idea, but advocates for immigrant children worry that could divert resources away from kids learning English.

“There’s plenty of districts and states who would do the right thing,” said David Holbrook, the executive director of the National Association of English Learner Program Administrators, which represents state and district staff. “But the reason we have laws, and the reason we see all the regulations, and the reason we have watchdog agencies” is because some would not.

In 1974, the Supreme Court ruled in Lau v. Nichols that the San Francisco Unified district violated the 1964 Civil Rights Act by failing to provide supplemental English language classes to students of Chinese heritage who did not speak English. The ruling led to significant changes in federal law and regulations, and spurred nationwide efforts to help English learners.

Several school districts, including Chicago, Denver, and San Francisco, entered into court-ordered settlements, known as consent decrees, to better serve English learners. But progress has been slow and uneven, and many English learners are still denied the services they should receive.

Three decades after those court orders, Chicago schools still did not have enough teachers or materials in native languages for English learners. In Denver, nearly 1 in 3 students failed to improve their English skills after two years in the district, test results showed.

Concerns about such issues aren’t confined to students’ English language skills and academic proficiency. Some advocates for English learners worry that Trump’s executive order declaring English as the official language of the United States could lead schools to put less effort into translating documents and conversations for immigrant families.

Then there’s the backdrop of how the president is enforcing immigration policy and who gets to remain in the country legally.

Trump is seeking to deport millions of immigrants who do not have legal status in the country, and he cleared the way for immigration arrests to happen at schools. He’s taken away the temporary status that protected hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans and Haitians from deportation. And Trump has pledged to strip birthright citizenship from children born to undocumented parents on U.S. soil.

Office helped train teachers and supported immigrant families

A dozen OELA staffers got notices that they would be placed on administrative leave as of Friday and terminated in June, according to the union that represents Education Department staffers who are not supervisors.

Two staffers listed in the January directory whose names did not appear on the union layoffs list had phone numbers that no longer worked. Another staffer had an email autoreply saying she was on extended leave.

“I looked at that list and I looked at all of the names on it and I realized: Oh that’s our entire office,” the laid-off OELA staffer said.

That seems to leave only the deputy assistant secretary, Beatriz Ceja, who was still responding to emails from organizations that work with English learners as of last week. Ceja did not respond to an email message or a voicemail from Chalkbeat seeking comment.

The Education Department layoffs are being challenged or questioned on multiple fronts. Twenty-one state attorneys general filed a lawsuit on March 13 challenging the staff cuts, and several members of Congress are probing them. Sheria Smith, a civil rights attorney who was among the laid-off Education Department staffers and president of the union that represents a dozen fired OELA staffers, said she did not think the layoffs complied with the law.

The first Trump administration tried to fold OELA into the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education back in 2018, but the plan ultimately did not come to fruition.

José Viana, who led OELA during the first Trump administration, told Chalkbeat in a written message that he is concerned about the cuts to OELA and “engaged in diplomacy efforts” with the new Trump administration.

“My focus right now is on providing guidance regarding the decisions that have been made, outlining the legal requirements, and working toward solutions that best support multilingual learners,” he wrote.

Oversight of Title III returned to OELA just over a year ago during the Biden administration. The Office of Elementary and Secondary Education oversaw Title III funds for 15 years before that.

Garibay led that transition and added four staffers to the team that handled Title III. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona saw the previous staffing level of two as “unacceptable,” Garibay said.

“We put systems in place so we could have better communication,” Garibay said. “Every time I would go to a state, they were just so grateful to have technical assistance.”

There can be benefits to the elementary and secondary education office overseeing Title III, because it can make federal program monitoring more consistent and cut down on some duplicative tasks, Holbrook said. But he also highlighted fears that existing staff won’t have the capacity to take on OELA’s workload.

One of the key roles OELA plays is in supporting universities, nonprofits, and others who train teachers who work with English learners.

Belinda Gimbert, an associate professor in education administration at The Ohio State University, has experienced that firsthand.

Gimbert is the project director for HELPERs, a program that helps pre-service teachers and paraprofessionals get their bilingual education teaching license and that trains existing teachers to work with English learners in small groups.

It also provides support for immigrant families, such as family-school connectors who translate over video chat — a key strategy for engaging Somali parents in central Ohio who speak Maay Maay, which is primarily an oral language. The program received a $3 million, five-year grant from OELA.

When Gimbert had a technical or financial question, she could shoot an email to OELA and they were quick to respond. If she didn’t understand a legal requirement, OELA staff would translate it into plain English and explain what it meant for her program.

Several times, OELA helped Gimbert quickly add a partner so she could serve more Texas schools without going over her original budget. That helped meet the sudden demand for adults to provide English language acquisition services when a wave of immigrant children moved to an area or military families relocated near a base.

“We’ve always had a person to lean on to be able to administer this grant,” Gimbert said. “Everybody is really concerned about making sure that we are in compliance.”

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.