This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy, and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

When catastrophic floods, fires, and hurricanes upend communities, the path of destruction they take may be random but the pain and suffering they cause is not.

Just as human-caused climate change can supercharge “acts of nature,” long-standing ethnic, social, and economic inequalities have left some populations highly vulnerable to extreme weather events. Immigrants, non-English speakers, communities of color, and low-income families typically experience disproportionate harms when disaster strikes, research shows.

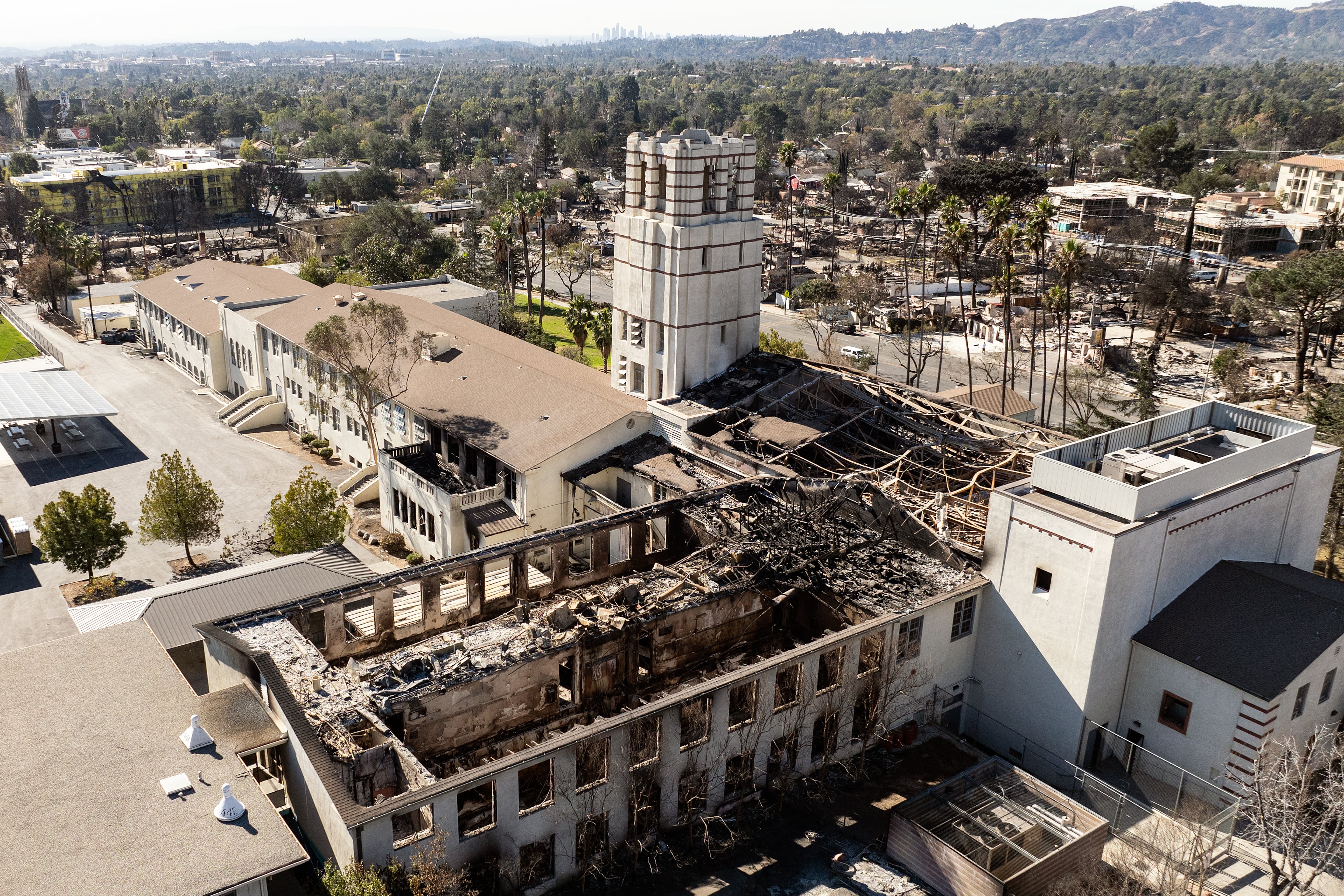

Now, a new analysis reveals how the disparate impacts of catastrophic events like the recent L.A. wildfires that killed 29 people and destroyed more than 16,250 homes and other structures, including several schools, extend to students, too.

UndauntedK12, a nonprofit working to make public schools resilient to climate change, has spent five years tracking how extreme weather events disrupt classes across the country. Staff there created an interactive map of “lost learning” time based on news reports of school closings, early dismissals, and other interruptions due to fires, floods, heat waves, and other extreme weather events.

Extreme weather is increasingly disrupting learning opportunities in multiple ways, said Jonathan Klein, a former schoolteacher and co-founder and CEO of UndauntedK12. “Historically marginalized and already vulnerable populations are disproportionately impacted by those events,” he said.

Klein had already been talking with EdTrust, a nonprofit dedicated to removing racial and economic barriers to education, about developing a more detailed national map to illustrate all the ways extreme weather disrupts learning. Then the L.A. wildfires broke out in early January, and they decided to explore how such a devastating event affected students. They analyzed school enrollment demographic data and scoured newspaper articles reporting school closures during the fires.

More than 750,000 kids went to more than 1,000 schools that were closed for as few as two days or more than 10 days in January, they found.

“Three out of four kids impacted by the Los Angeles wildfires are socioeconomically disadvantaged,” Klein said. “Two out of five kids impacted by the wildfires are multilingual learners and one out of 10 is a student with disabilities.”

The report is not peer-reviewed and makes no claim to being comprehensive, Klein said. But it’s important to compile statistics like this, he said, because some students have specific needs that are seriously affected by the interruption to classroom learning. They need to return to learning and a stable school setting most urgently, he said.

Schools provide nutrition and a stable environment for students from households where they may not have enough to eat, live in overcrowded or unsafe housing conditions, or lack adequate adult supervision.

The analysis found that two-thirds of the students affected by the L.A. fires are Latino, many of whom are learning English in school. Disruptions of their schooling exacerbate learning challenges for these students, who are particularly dependent on in-person language support, the authors said.

Many parents of English-language learners are immigrants who often depend on local schools for support and services, including school meals and after-school programs that help working parents who can’t afford child care. And about 8% of households in California include a family member who is an undocumented immigrant, the authors note. For children now living in constant fear that a family member will be detained or deported under the Trump administration’s harsh immigration policies, school closures create even more stress, experts say.

“The basic facts are undeniable,” said Matthew Kraft, associate professor of education and economics at Brown University, who was not involved in the report. “Extreme weather events, made more frequent and intense by climate change, pose a clear and present danger to our education system.

“This new analysis serves to quantify the scope of the disruption to learning and damage to schools caused by the L.A. wildfires,” Kraft said. “To put these numbers in perspective, the fires impacted more K-12 students than there are in the entire state of Oklahoma.”

The extreme weather multiplier effect

Studies show that school closures and chronic absenteeism caused by extreme weather events have an outsize detrimental effect on kids’ academic success. Missing one week of school from extreme weather-related school closures is the equivalent to missing two to three weeks from some other kind of absence or school closure, Klein said. “There’s something about the trauma and the nature of these events that has a pretty significant impact on kids’ learning and social and emotional well-being.”

A 2023 peer-reviewed study in the journal Economics of Education Review found that nearly all students had lower test scores after Hurricane Florence triggered closures in North Carolina elementary and middle schools in 2018. White students and high-performers were the least affected. But aside from the students who had performed in the top 20 percent of their class the previous year, nearly every group of students experienced some decline in learning due to the school closures.

Increasing instances of natural disasters, such as the L.A. wildfires or hurricanes on the East Coast, underscore the urgent need for schools to increase their climate resiliency and plan for long-term recovery strategies, said Megan Kuhfeld, director of growth, modeling, and analytics at NWEA, an education research and assessment arm of HMH. She was not involved in the analysis.

Preparations to mitigate the long-term negative impacts of disasters on student academics are vital for children’s social and emotional well-being, Kuhfeld said. “Before a natural disaster strikes, school districts should develop an emergency response plan that covers both short-term and longer-term needs of students. Short-term priorities include getting schools safely reopened, and if that is not possible, identifying alternative locations for students to be able to attend classes.”

Longer-term, Kuhfeld said, districts need plans to reestablish stability in students’ lives, make up for missed instructional time and help kids process the traumatic effects of the disaster.

A recent survey from Stanford University’s Center on Early Childhood found that one in two California parents with young children worry about how wildfires, drought, flooding, and extreme heat affect their kids. Many parents said they were stressed about needing to evacuate in case of fire, having their insurance dropped, and not being able to pay their summer utility bills.

The traumatic toll the L.A. fires have taken on children “cannot be underestimated and may portend long-term difficulties,” child development experts told the Los Angeles Times.

These harmful effects are compounded for the most vulnerable kids, like those identified in the report.

“We were already in an environment where immigrant and LGBTQ+ families might be feeling more unsafe than usual,” Klein said. “That’s an existing challenge and now [extreme events] act like a multiplier.”

Klein has worked in and around schools for decades but started thinking seriously about how climate change affects learning when his daughter asked him to be a chaperone at a youth climate strike in San Francisco in 2019.

“I spent a day with like 25,000 teenagers,” he said. “I didn’t know a member of Generation X that was operating with the urgency or ambition that those young people were asking for.”

He left the strike committed to figuring out what he could do to help create equitable, climate-resilient schools.

“We already knew that chronic absence and generally missing school has an impact on student learning,” Klein said. “The big idea here is that the disruption and lost learning from extreme weather closures might be even more significant.”

The fires in California offer lessons for the types of disruptions extreme events will increasingly impose on schools across the country and the urgent need for educational leaders to invest in resilience, the authors say.

“Schools are at the center of every community and can be reimagined and repositioned not only as innovative hubs of learning but also as community assets when needed for emergencies,” said Brenda Cassellius, who started as superintendent of Milwaukee Public Schools on March 15 and did not contribute to the report.

They can function as shelters, cooling centers, food kitchens, or electricity hubs when there are outages, said Cassellius, a longtime advocate for equitable education.

But U.S. schools, many with years of deferred maintenance, simply can’t keep up with the impacts of climate change, said Cassellius.

“We need a full-scale investment at all levels in our aging and deteriorating school infrastructure,” she said. “This is particularly true in our urban school districts that serve our most vulnerable students.”

Many school facilities across the country don’t have advanced filtration for wildfire smoke or cooling systems or shaded playgrounds to cope with heat waves.

Hot school days disproportionately affect children of color, a 2020 peer-reviewed study found, accounting for about 5 percent of the gap in PSAT scores between white students and their lower-scoring Black and Latino peers, who are more likely to attend schools without adequate air conditioning.

“We’re trying to elevate this issue of the need for climate-resilient infrastructure to state and local policymakers,” Klein said. “The reality is there will be more [extreme events], and they’re happening with increasing frequency and extremity.”

Klein and his colleagues are encouraging education leaders to focus on climate mitigation as well as adaptation. “The country spends $100 billion every year on school infrastructure, and school infrastructure burns a lot of fossil fuel.”

The country’s roughly 100,000 public schools emit 78 million metric tons of carbon emissions each year, according to a 2021 report from the Climate and Community Institute, a progressive think tank.

But it doesn’t have to be that way, he said.

“What both the science tells us is needed and what young people are urgently asking us for is to stop making the problem worse,” Klein said. “And to choose technologies that do not contribute to planet-warming, extreme weather-causing greenhouse gas emissions.”