Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

When the devout Muslim parents of a second grader learned their son would be reading a story at school about a prince who falls in love with a knight, they asked to opt him out.

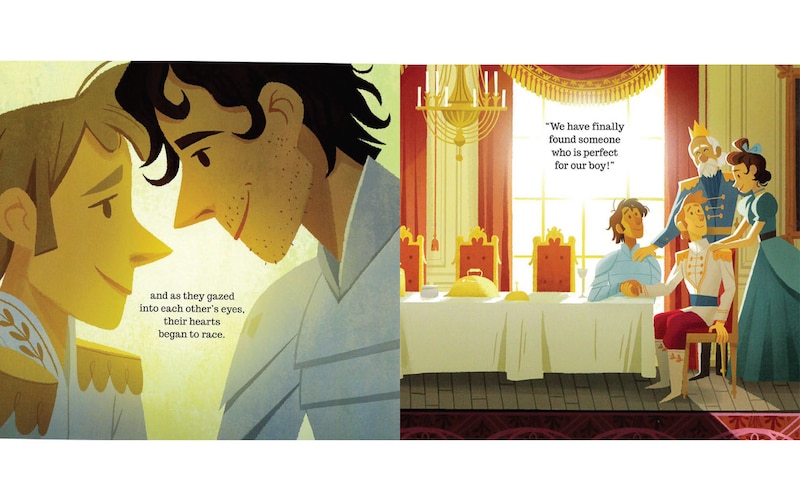

The story about a man who marries another man after they team up to vanquish a dragon went against their religious teachings, the parents said. They wanted an alternative assignment.

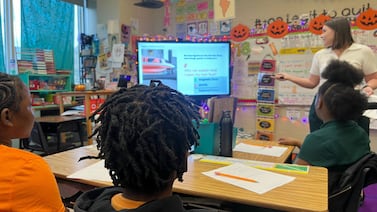

The book in question, “Prince & Knight,” was one of several books that Maryland’s Montgomery County Public Schools added to its English curriculum in 2022 as part of a district initiative to put more books featuring LGBTQ characters in elementary school classrooms.

At first, the second grader was allowed to sit outside the classroom during discussions of the book. But a few days later, the district’s school board decided parents could no longer opt their kids out, later citing the volume of opt-out requests. Teachers would also stop informing families when they used one of the LGBTQ-themed books in class.

Many parents spoke out against that decision. The second grader’s parents and other families sued Montgomery County Public Schools to reinstate the opt-out option. Two federal courts let the no opt-out policy stand. Now, the Supreme Court — with a conservative majority that’s likely to be sympathetic to the burgeoning parental rights movement — is set to weigh in. Oral arguments in the case, Mahmoud v. Taylor, are scheduled for Tuesday. A decision is expected by June.

At the heart of the case is a longstanding tension between the power of parents to direct their children’s education and the authority of public schools to set their own curriculum. The high court’s ruling could decide whether parents have the right to opt their children out of any content that they see as at odds with their faith — and how far schools must go to accommodate them.

The case comes as Democrat-led states such as New Jersey, Illinois, and California have adopted curriculum that’s more inclusive, especially on topics of gender and sexuality. Meanwhile, Republican-led states like Florida, Georgia, and Louisiana have passed new laws that give parents more insight into what their kids are learning and the ability to opt out of certain lessons.

If the Supreme Court sides with the school district and decides parents don’t have the religious right to opt out, some say that could open the door to schools adopting curriculum without much regard for parent or community feedback. The views of minority parents, especially, could be ignored.

If the parents prevail, some worry schools would remove certain content altogether to lessen the chances of opt-out requests. That would be a set-back for schools and families that support efforts like those in the Montgomery County district to make curriculum more inclusive.

A ruling for the parents also could upend school operations, some legal and education experts say. It could force already stressed teachers and principals to send notifications, devise alternative assignments, and catch kids up if they miss other content during an opt-out.

“Do you have all the parents list out all the things that they believe at the start of the year, so you know and can tailor what you teach?” said Morgan Polikoff, an education professor at the University of Southern California who’s studied Americans’ views on opt-out policies. “It’s not hard to see how it could spiral out of control really quickly and really undermine the ability of public schools to perform their basic core function: teaching kids.”

Case centers on religious rights, LGBTQ inclusion

Several Montgomery County parents said in court filings that exposing their kids to the new books at school violated their right to free exercise of religion, which is guaranteed by the First Amendment.

“Our son loves his teachers and implicitly trusts them,” wrote one second grader’s parents who follow Roman Catholic and Ukrainian Orthodox teachings. “Having them teach principles about sexuality or gender identity that conflict with our religious beliefs significantly interferes with our ability to form his religious faith.”

Lawyers for the parents say the books’ positive portrayals of LGBTQ characters and themes indirectly pressure kids to adopt that thinking. But they say what their parents want is different than laws like Florida’s that bar teaching about gender identity and sexual orientation in certain grades.

“Our parents aren’t asking for an LGBTQ-free classroom,” said Colten Stanberry, one of the attorneys at the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty who is representing the parents in the Supreme Court case. “They are not saying the books can’t be on the shelves. They are specifically challenging instruction,” such as reading the books in class and talking about them with teachers.

In a 2-1 ruling, a federal appeals court sided with the school district. Making kids read books that don’t align with their religious teachings is not a violation of families’ rights, they wrote, because they weren’t forced to change their beliefs or actions. Parents were still free to talk about the picture books with their children and teach them what they wanted, the judges wrote.

That interpretation follows how federal courts have ruled in other similar cases.

Montgomery County Public Schools officials have said they adopted the set of LGTBQ-inclusive books as part of a broader effort to make the district’s curriculum more culturally responsive with texts told from multiple viewpoints. The district is known for its racial, ethnic, and religious diversity, although that diversity hasn’t always equaled harmony.

Similar efforts, according to court documents, included the addition of books about the Black civil rights icon John Lewis and a novel about a Chinese-American immigrant family.

Teachers were expected to use the books as they would any other part of the curriculum. That could mean reading them aloud or putting them in classroom libraries, the district said in court filings.

The books were meant to teach critical reading skills and not for instruction explicitly about sexual orientation or gender identity, the district said.

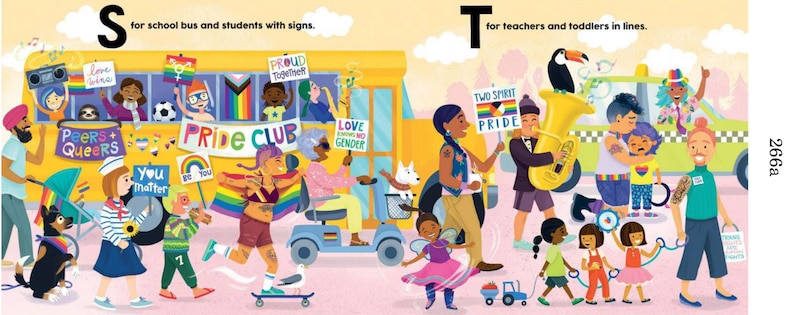

In addition to “Prince & Knight,” the stories included “Pride Puppy!” an alphabet book for preschoolers and kindergartners about a dog that encounters various scenes at a Pride parade, and “My Rainbow,” in which a Black mother sews a colorful wig for her transgender daughter. And in “Love, Violet” a young girl worries about whether her same-sex crush will like the valentine she made her.

The district also gave teachers guidance about how they could respond to potential questions or comments from students. If a student said being gay is wrong and not permitted in their religion, teachers could respond: “I understand that is what you believe, but not everyone believes that. We don’t have to understand or support a person’s identity to treat them with respect and kindness.”

In another instance, if a child asked about what it meant to be transgender, a teacher could say: “When we’re born, people make a guess about our gender and label us ‘boy’ or ‘girl’ based on our body parts. Sometimes they’re right and sometimes they’re wrong.”

Still, some parents and school leaders worried the books used unfamiliar words without defining them. Others questioned whether it was appropriate to show kids in romantic relationships, regardless of their sexual orientation. The district eventually pulled “Pride Puppy!” and “My Rainbow” from classrooms, the Washington Post reported, because kids may not have understood the texts without explicit instruction on vocabulary outside the bounds of the lesson.

“There’s reasonable discussions to be had about what’s age appropriate in curriculum,” Polikoff said. But, Polikoff, who is gay, said this case is more about: “Does acknowledging that gay people exist burden other people’s religious views? Where is the line here?”

How a ruling for the parents could affect schools

If the justices side with the parents in this case, it could give families “broad authority to request opt-outs along a wide array of different issues,” said Justin Driver, a constitutional law scholar and professor at Yale Law School.

If the teacher wants to give a pop quiz about a book most kids have read, they’d have to write a completely different test for kids who opted out, Driver said. Teachers could end up refereeing “dueling free exercise claims” from parents with opposing religious beliefs. Teachers would have to avoid stigmatizing children who’ve opted out, as well as children who see themselves in the content other kids are skipping.

Given past court decisions, it’s unlikely the justices would confine opt-outs to certain topics or student grade levels, Driver added.

“Just because some people may be uneasy with this sort of material today, it doesn’t mean that the federal judiciary should be commandeering local control over public schools,” said Driver, who co-authored a friend-of-the-court brief in support of Montgomery County Public Schools.

Glenn Branch, the deputy director of the National Center for Science Education, has seen how this can play out.

Sometimes it’s easy for teachers to come up with alternative assignments. When parents object to their kids dissecting animals, Branch said, teachers can swap in a plastic or virtual model.

But when religious parents object to their kids learning about evolution, there really isn’t a substitute, Branch said. Evolution comes up so many times in biology class — from learning about the structure of a cell to taxonomy to genetics — that teachers would need “revolving doors” for kids to cycle in and out. That would be disruptive for their classmates, too.

“It would be kind of like saying: ‘Well, we’re not going to do fractions,’ in a math course,” Branch said.

Lawsuit’s supporters: Opt-out right isn’t burden on schools

Lawyers and scholars in the parents’ camp, meanwhile, say giving parents the right to opt out of certain content on religious grounds wouldn’t dramatically change public education.

Nearly all states permit opt-outs for sex ed or lessons on human sexuality, they note. Texas permits parents to opt their kids out of lessons on any topic for religious or moral reasons.

“A lot of school districts are, in fact, already doing what the parents are asking for here,” said Stanberry, the parents’ attorney.

Douglas Laycock, a constitutional law scholar and law professor emeritus at the University of Virginia and the University of Texas, said he did not expect schools to be flooded with opt-out requests. Laycock, who co-authored a friend-of-the-court brief supporting the parents, added that the topics parents will likely object to are predictable: sex and evolution.

If students skip broad swaths of the curriculum, that shouldn’t come without consequences, he said. For example, a student could opt out of evolution lessons, he said, but then “you can’t get credit for biology.”

Still, he can imagine a scenario in which schools get overloaded with parents’ opt-out requests.

“If you have large numbers of people demanding alternative assignments for lots of different parts of the curriculum, at some point it’s going to become unworkable,” he said. But if parents’ requests are limited to a smaller piece of the curriculum, as he believes they were in Montgomery County, schools should be able to make that work.

The reason the school district got so many opt-out requests, he added, is because the curriculum was age-inappropriate and lacked broad community support.

Stanberry, too, could imagine another case in which the school district’s responsibility to educate children — especially in core subjects like reading and math — could trump a parent’s religious right to skip that content.

“When it comes to matters that are particularly sensitive to religion, especially matters of human sexuality, gender identity,” he said, “that’s a place where parents should get to decide.”

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.