Public health, explained: Sign up to receive Healthbeat’s free New York City newsletter here.

For Panagiotis Sotiropoulos, a physician assistant, most days bring nosebleeds, ankle sprains, and headaches. There’s diabetes to control and asthma attacks to manage — sometimes so severe they require use of oxygen tanks.

To provide all this care, Sotiropoulous isn’t in a hospital or an urgent care facility. He’s just down the hall from where his patients, who range from 11 to 19 years old, spend most of their time.

Sotiropoulos is the medical provider for a school-based health center in the South Bronx.

“As soon as I walk out of the clinic, it’s like I’m in a different world,” he said. “I smell the food from the cafeteria, I see kids dressed up in uniforms.”

About 250 in-school clinics like this are scattered throughout New York state, reaching roughly 250,000 students in underserved rural and urban areas. But providers and advocates of these clinics fear that this system of care could soon be jeopardized due to a state overhaul of how school-based health centers are paid through the state’s Medicaid system.

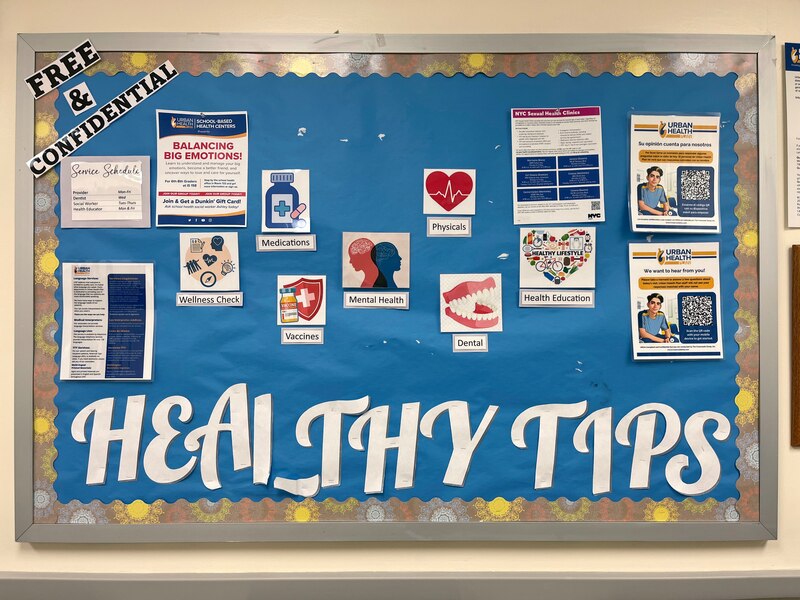

For decades, these clinics have provided a wide range of health care to students, offering vaccines, teeth cleaning, and help for mental health struggles, all at no cost. The clinics are integral to their schools and neighborhoods, providing health services in areas where access to care can be limited and issues like asthma can be particularly widespread, advocates say.

The clinics are run by a range of providers, from major hospital systems to nonprofits to federally qualified health center systems like Urban Health Plan, which runs Sotiropoulous’s clinic, as well as others in the Bronx and Queens.

Under the current system, the clinics bill Medicaid on a fee-for-service basis. Last fall, however, Gov. Kathy Hochul announced that a long-delayed school clinic payment overhaul would come due this spring. The clinics would be “carved in” to the state’s Medicaid managed care program, requiring them to negotiate a slew of contracts with private health insurance providers.

Providers at school-based health centers are worried the change could mean lower reimbursement rates, reduced services, and clinic closures. And they’re also concerned about what any cuts to Medicaid could mean for the system, as congressional Republicans seek $880 billion in budget cuts over the next decade.

“This is just the worst possible time for you to do anything to shake the foundations of your safety-net care,” said Sarah Murphy, executive director of the New York School-Based Health Alliance, an advocacy organization.

The state postponed its payment overhaul deadline, originally set for April 1, to Thursday at the earliest. Meanwhile, the state budget is nearly a month late, and lawmakers have expressed opposition to the transition, proposing to abandon it in their one-house budget proposals.

The Health Department told providers that the transition would occur no sooner than May 1, “but we cannot comment further at this time due to ongoing budget negotiations,” spokesperson Danielle R. De Souza said in a statement.

School clinics bring comprehensive care to students

New York’s network of school-based health centers has long been a national model, said Dr. Veda Johnson, a professor of pediatrics at the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, who helped open the first school-based health clinic in Georgia in the 1990s.

Johnson’s research into school-based health centers has shown that they are of “tremendous value,” she said, not only by improving preventative care for children, but also by decreasing the burden on the state Medicaid system through reductions in emergency room visits.

The clinics also solve the logistical problem of accessing children’s health care, said Adria Cruz, deputy director of health programs and integration at Children’s Aid, a New York City nonprofit that runs multiple school-based health centers.

“Often the parents have hourly paid jobs,” she said. “Taking time off from work to take their kids to see the doctor could mean that they’re not working that day.”

That could mean annual physicals that don’t happen on time, dental care that gets postponed, or a student coming into school sick because there are no other options. A school-based clinic means that care can happen as part of the school day.

Dr. Viju Jacob, the medical director and vice president of medical affairs at Urban Health Plan, received some of his own early dental care at a school-based health center in the Bronx.

“Many school-based health centers offer the whole-body experience that health care has been talking about forever and ever: integrating services and making sure that they have access to not just physical health, but mental health and dental health,” said Jacob, a pediatrician and vice chair of the New York School-Based Health Foundation.

How a payment overhaul could impact care

While the services that school-based health centers provide are essential, advocates and providers say, the system has always been somewhat financially tenuous. New York City has already seen some of its school-based health clinics close due to budget constraints, and advocates worry that the state’s reform plan could lead to further closures or service reductions.

The state has previously explained the payment overhaul as an effort to integrate school-based health services into the “larger health care delivery system” and coordinate services with children’s primary care providers.

Murphy, of the New York School-Based Health Alliance, said that the current Medicaid fee-for-service system is generally efficient and health centers already work closely with pediatricians.

Under the governor’s plan, school-based health centers will need to negotiate contracts with many private insurers. Advocates are concerned that will mean increased administrative burden on clinics, lower reimbursement rates, and payment delays. As the new deadline approaches this week, Murphy said that while negotiations are underway, they have been complicated, and in many cases, aren’t finished.

For two years following the transition, Medicaid managed care programs will be required to pay school-based health centers no less than the current rates they receive, but providers worry about what could happen next.

Sen. Gustavo Rivera, a Bronx Democrat and chair of the Senate Health Committee, has been particularly outspoken in opposing the state’s plan. He sponsors a bill in the state legislature that would permanently carve out school-based health centers from the state’s Medicaid managed care program. Hochul has vetoed previous versions of this bill.

“The administration is insisting on doing a change that makes no sense, that nobody wants,” he said. “The schools don’t want it, the providers don’t want it, the insurance companies don’t want it, the kids and the parents certainly don’t want it. And they’re just, in a boneheaded way, going forward and doing it.”

A South Bronx clinic facing an uncertain future

On Friday, the waiting room at the school-based health center in the South Bronx was filling up. The clinic serves students from three schools: Bronx Latin, Bronx Career & College Preparatory High School, and the Dr. Richard Izquierdo Health & Science Charter School.

Nearly 70% of the students at the schools — more than 900 students — are enrolled in the clinic, according to Jacob. In addition to obtaining medical care, students can see a dentist, talk to a behavioral health specialist, or seek out reproductive and sexual health resources.

Carolyn O’Neal, a licensed clinical social worker and behavioral health manager, helps students navigate issues from relationship problems to anxiety and depression. Many behavioral health issues benefit from early intervention, she noted, and school-based clinics can be an ideal place to notice students who are struggling — and step in to help. The same is true for reproductive health care, she said.

“Sometimes you can just tell, when there’s a lot of nervousness, when they come with a group of friends — we know someone needs something,” O’Neal said.

Down the hall, Sotiropoulos jokes that he runs a mini emergency department. It’s a far cry from the in-school health care he remembers from his own education in Queens: a school nurse dispensing Tylenol in the basement.

The repercussions of the approaching payment overhaul are still uncertain, he said.

“I’m worried, honestly. I don’t know what will happen,” he said. “I just hope we stay open. I hope we still offer this. We’ve been doing this for years.”

Eliza Fawcett is a reporter covering public health in New York City for Healthbeat. Contact Eliza at efawcett@healthbeat.org .