With just 17 percent of black students and 30 percent of Latino students scoring proficient in reading at Chicago Public Schools — compared with nearly half of white and Asian students — the city’s next leader must confront the critical question of how to boost student performance and narrow the racial achievement gap.

Chalkbeat asked candidates for mayor how they would go about doing that while forging a more equitable school district. You can see their answers to this question in full below this article or read all of their responses to our six-part questionnaire here.

Of the 11 candidates who responded to our questionnaire, only a few offered concrete plans or proposed big, new ideas. Others were vague or downplayed the importance of academic performance in favor of focusing on vocational education. Most said they would focus on increasing funding — an uncertain promise, at best, given the precarious financial situation of the city and the state. Others talked about zeroing in on entire neighborhoods needing more investment, or rooting out racial inequities in decision-making at the district.

Related: Who’s best for Chicago schools? A Chalkbeat voter guide to the 2019 mayor’s race

State Comptroller Susana Mendoza was among several Chicago mayoral candidates who honed in on neighborhood solutions. She said she would focus on building thriving business districts and boosting local business owners to create more economic opportunity in neglected neighborhoods. She touted those plans alongside promises to improve public safety and invest in struggling schools.

More recently, researchers, educators and policy makers have pivoted conversations about achievement gaps toward talk about gaps in opportunity — to explore systemic failures by institutions and adults that impact students’ academic performance — like inequitable school funding and resources, lack of access to qualified teachers and high-level courses.

Both Cook County board President Toni Preckwinkle and former alderman Bob Fioretti emphasized the need to provide equitable funding and resources to schools, with an emphasis on neighborhood schools.

“I will invest in resources to educate the whole child,” Preckwinkle’s response read. “This means support in and out of the classroom so all children can better cope with challenges at home that might lead to lagging behind.”

Related: How one Chicago principal is leaning on data to help black boys

Bill Daley, a former U.S. commerce secretary and Obama administration chief of staff, sidestepped talk of achievement gaps altogether in favor of increasing vocational pathways, stressing that college can be great — but it isn’t for everybody. Daley stressed that finding a good job is a critical ingredient to students living good lives, regardless of their test scores.

Daley touted his plan to merge the city’s school district with its community college system, which offers credentials and training for many jobs that don’t require a bachelor’s degree as a way to prepare young city denizens for the labor market — while helping reduce college debt via free tuition for students who want more degrees.

Like Daley, businessman Willie Wilson advocated more vocational education.

Wilson wrote in his response, “I’m all for higher education and I want to do more to encourage more of our graduates to go on to college.”

“However,” he said, “the majority of students do not go on to college. Therefore, we need to give them options and prepare them for other paths that will lead to a successful life.”

Paul Vallas, former Chicago schools chief and budget director, provided the longest and most detailed response. He promised to “obliterate the achievement gap” with a program he dubbed “Universal Prenatal to the Classroom.” The program would offer mothers universal prenatal health care and postpartum support, and provide families universal pre-kindergarten and kindergarten.

Vallas didn’t put a price tag on his idea or specify how he would pay for the initiative, which could be more ambitious than Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s $175 million universal preschool rollout.

Research finds that the gap between black and Latino students and their Asian and white peers exists before kindergarten. It doesn’t increase much from year to year so much as it persists, as Andy Porter, a leading national expert on standardized testing, wrote in this article.

Candidate Jerry Joyce, a Chicago lawyer and former county prosecutor, also focused on early childhood education to tackle the achievement gap. He proposed piloting a program that would divide students into small classes taught by the same teacher from pre-K to third grade with a focus on reading comprehension and individualized instruction.

Other candidates like Lori Lightfoot, Amara Enyia and La Shawn K. Ford focused more on addressing the district’s problems with race and inequity.

Related: Here’s some advice for CPS’ future Chief Equity Officer in year one

Research has found many factors contributing to the gap, including, race, class and environment, as well as poverty, incarceration, trauma and lack of resources in segregated communities occupied by historically oppressed and neglected groups. Black families in particular have weathered discrimination, institutional racism and other structural barriers to education and wealth since the days of slavery.

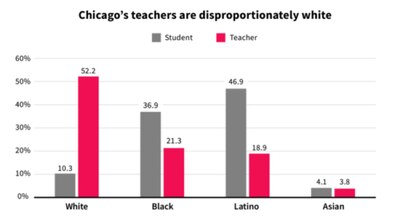

State Rep. Ford argued for diversifying the teacher ranks to better reflect the student population, citing research that finds black and Latino students of color perform better, attend school more often, suffer less bias and enjoy higher expectations when they have teachers who look like them. His response noted, “although the majority of the students at CPS are students of color, the majority of the teaching staff is not.”

Related: Diversifying the pipeline — a look at teacher diversity at Chicago Public Schools.

Lightfoot, an attorney and former federal prosecutor, proposed a detailed framework for tackling racial inequity. She would conduct a systematic review of how policies, practices, and budget decisions affect ethnic and racial groups and would integrate that approach into district decision-making and the school improvement plans overseen by Local School Councils.

“I will follow the lead of other school districts around the country and help create policies and practices that undo the systems and structures that created and perpetuate inequities of opportunity and academic achievement,” said Lightfoot, who used to oversee police disciplinary cases as president of the Chicago Police Board and is the first openly lesbian candidate to run for Chicago mayor.

Enyia, a policy consultant and director of the Austin Chamber of Commerce, said she would promote equity and achievement by creating a citywide Office of Equity to serve as a watchdog over policy and budget decisions and ensure district policies and school improvement plans are equitable and fair. Enyia said she would also increase support for Local School Councils given their role in approving school budgets, academic plans and hiring principals.

Use the tool below to peruse candidates answers to Chalkbeat Chicago’s questions about how they would close the achievement gap and forge a more equitable school district. Scroll down to see every candidate’s response, or click on individual names to narrow the field.