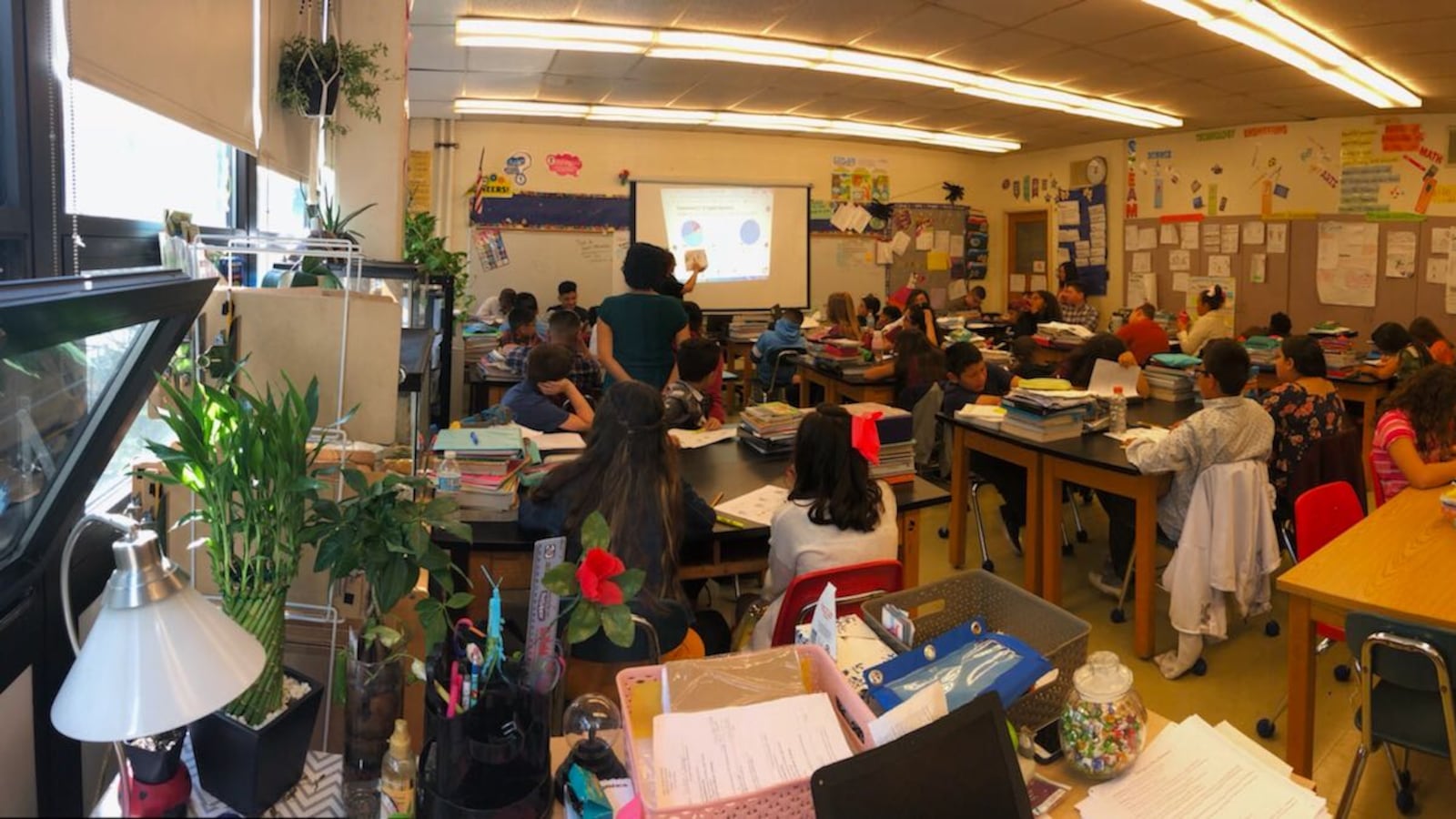

With 45 sixth grade students in her science classroom at Grissom Elementary, Melissa Ramirez doesn’t have a moment — or an inch of physical space — to waste.

She tries to follow the district’s science curriculum standards, which call for small group discussion. But students can’t hear over each other in the jam-packed classroom. Chairs crash into each other with the slightest movement, leading to bickering, while Ramirez attempts to translate complex science terms to the handful of children not yet fluent in English.

“My sixth graders can’t learn like that,” she said Friday, as she joined her fellow teachers picketing in front of the Far South Side school in Hegewisch. “At my last school, they were able to learn at a much higher level because there were fewer kids.”

Related: Live update from Day 2 of the Chicago teachers strike

Grissom, long plagued with overcrowding that shows little sign of abating (its kindergarten has 36 students), shows how cram-packed classrooms affect learning, its educators said during the second day of the Chicago Public Schools teachers strike.

The problem is so widespread and acute — and thus costly to resolve — that rank-and-file picketers acknowledge that the likely contract solution, which is to provide more money to schools to hire more classroom aides, will generally fall short.

Class size has emerged as a central issue at the bargaining table, and both sides acknowledged progress in talks. The union wants Chicago Public Schools to lower its caps to 20 in kindergarten, 24 in first to fifth grades, and 28 to middle and high school. And it wants to compensate teachers whose classes that exceed those counts — not an uncommon provision in union contracts elsewhere.

Chicago Public Schools CEO Janice Jackson said in an interview Friday morning with WGN-TV that the city’s latest proposal would give schools “additional resources, such as teaching assistants,” and that its proposal would “start with the classrooms with most need.” The proposal also reportedly includes $9 million in discretionary funds for a committee charged with enforcing measures to lower class size.

Related: Closed door or open negotiations: Should Chicago bargain in public?

Jackson also spoke to the complexity of the issue. For instance, the district can’t control how many kindergarteners enroll at a school in a given year, she said. “You can’t predict how many children show up in kindergarten or first grade.”

She said her team has pledged to work with school administrators to “make sure they are not overenrolling in a way that contributes to outsized class sizes.” Schools receive money for each student enrolled, and thus larger class bring in more dollars to a school.

So far, a final contract solution remains elusive.

On the picket line, teachers hope bargainers consider their concerns. For instance, aides may lower the ratio of adults to children, but some schools borrow aides to oversee recess or lunchrooms. Other schools rotate aides, making consistency and planning a struggle.

Teachers interviewed by Chalkbeat also said that the district doesn’t provide collaborative planning time, so classroom strategy is determined in quick conversations here and there.

Ramirez has a teacher’s assistant and a shared special education classroom assistant. But the latter is sometimes only available for half the class period.

Across town, Ted Wanberg, a longtime kindergarten teacher at Peirce Elementary in Edgewater, said he gets some help from a recess aide for his class of 30, but it’s not all day.

“What I value in a smaller class is being able to sit with each child, look them in the eyes. It’s important with young children—and it’s hard to do with 30-plus in a classroom,” he said Thursday outside of his school while walking the picket line.

Wanberg knows the difference smaller classes make. A decade ago, he had only 22 or 23 in a class. Adding an aide, he said, still means “more bodies in the class. We need fewer.”

While a committee oversees Chicago’s nominal class-size cap — 28 in kindergarten through fifth grades,, 31 in higher levels — it doesn’t have any authority. Some 1,000 classrooms exceeded the caps last year, according to data obtained in December by the group Parents 4 Teachers.

Prior to the strike, teachers whose classes exceed the caps file a union grievance.

Molly Mehl and Meghan Residon at Ravenswood Elementary both did that last year. Each teacher had 34 students in a kindergarten class at Ravenswood — one of the highest averages across the district, according to data obtained in December by the group Parents 4 Teachers.

Each waited two months for the district to agree to give them an aide. But the year ended, and so did the relief. This year, Mehl again has 34 students in kindergarten. She’s had to start the process again.

Residon got moved to second grade. This year, her class has 28 students.