I was watching my last-period class devolve into chaos. The kids were wound up after another day of indoor recess. I was exhausted, and none of my usual attention-getters was garnering any response.

The class got louder, I got frustrated, and I’ll admit it — I did a bad thing.

I grabbed the chime on the projector cart and rang it. Not once, not twice, but over and over and over again until everybody stopped talking.

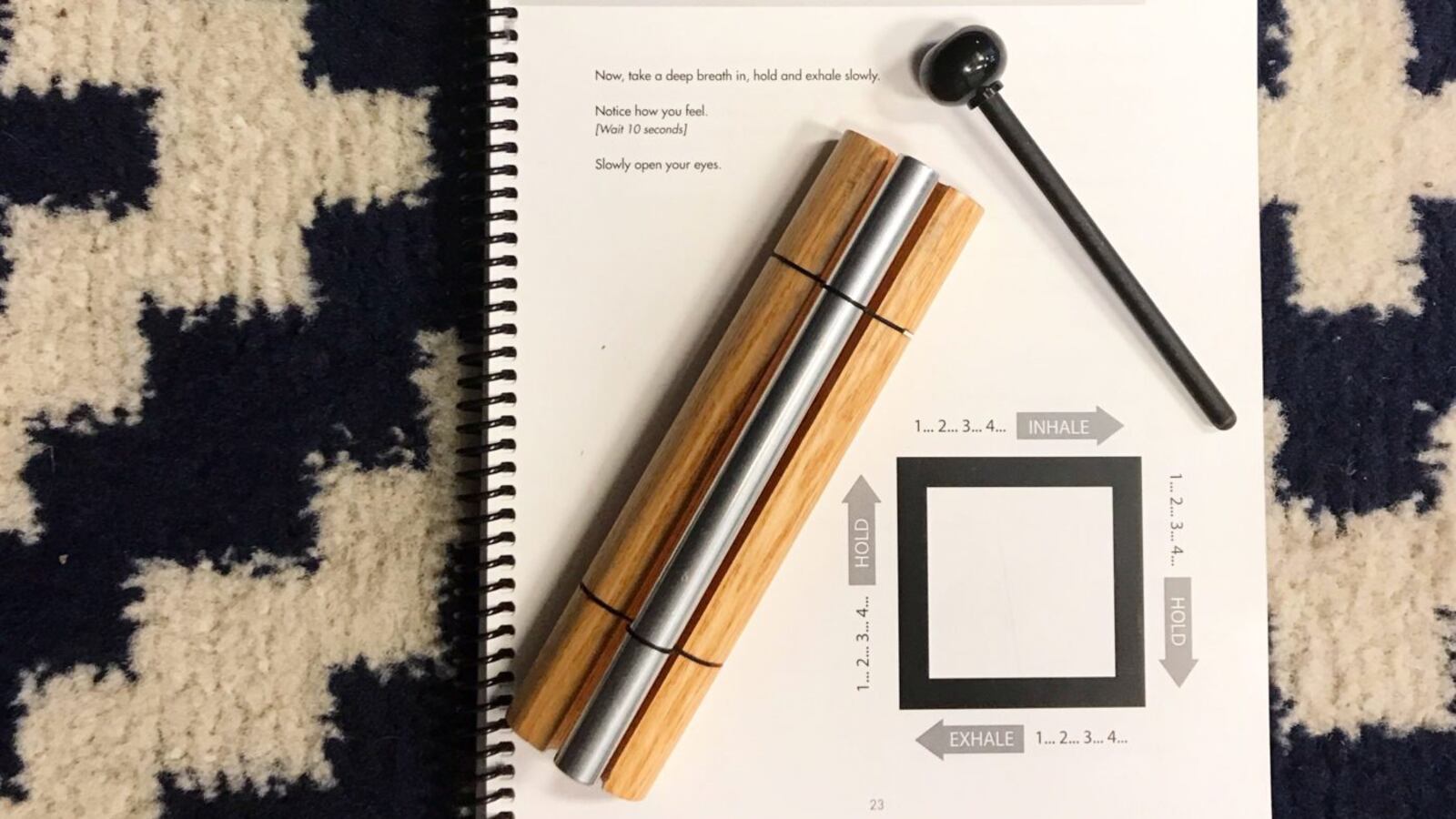

Maybe that doesn’t sound so bad, but the focusing chime is a meditation tool, OK? It’s a part of the Calm Classroom curriculum, and scaring kids into silence is so not what the focusing chime is meant to do.

Please forgive me. Who among us is at their best in the midst of the gray midwinter?

The more centered teacher in me knows that those end-of-my-rope moments are exactly what Calm Classroom is meant to help us breathe through. If you haven’t heard of it, Calm Classroom is a curriculum meant to help “manage stress and achieve emotional well-being.” Schools that purchase it get a scripted manual, audio recordings, and (oops) a wood focusing chime to use three times daily in the classroom. The manuals offer breathing, stretching, focusing and relaxation techniques for kids from pre-K through high school.

I know this kind of thing gets a hard pass from people who write it off as pseudo-science, but I’ve been watching it work for my students. There’s some research to back me up, too.

Embodiment, or paying purposeful attention to the sensations in the body; mindfulness; compassion — these skills will help our kids navigate a swelling sea of anxiety fueled by social media and the like. I really believe that.

I use the curriculum often with my students. If I don’t have time to unearth the manual from under a pile of papers and finger puppets, I’ll simply ask everybody to close their eyes and breathe with one hand on their heart and one hand on their belly. I’ll ask them to feel their heartbeats slow down, to remember what it feels like to be able to relax their bodies all by themselves.

It’s really that easy.

Here’s the catch, though. This curriculum won’t work if we don’t. Good teachers know that the “I do, we do, you do” method gradually releases responsibility to kids in a way they can manage. It sets them up for success. It requires that we master the content before they do.

It’s awfully hard to teach what you don’t know. If I can’t stand in front of a broken copy machine and take a deep breath instead of fantasizing about taking a bat and going all “Office Space” on it, how can I expect them to do any better when things go wrong?

If I can’t respectfully solve conflicts with my colleagues, rather than talking behind their backs or tattling to my boss, how can I ask a greater measure of maturity from 7-year-olds?

I can’t, and we all know it. That’s why I think teaching mindfulness is a great second step. It’ll work, just as soon as we do.

Being a good teacher is a promise to be perpetually learning. This is a no-stagnation-allowed kind of career, like it or not.

If we believe it’s true — and I do — that mindfulness will help students feel more positive about school, pay sustained attention to certain tasks, and (gasp!) even lead to higher test scores, then we have to learn how to teach those techniques with authenticity and authority.

I do, we do, you do. It’s a tried-and-true method for a reason.

So I’ll unroll my yoga mat, even when I’m tired. I’ll find a 5-minute meditation on the Insight Timer app before school. I’ll breathe (and curse) and breathe at that $*&@-ing copy machine. And then — only then — will I ask the same of my students.

Anne Halliday is a pre-K through 8th grade International Baccalaureate world languages teacher at Pulaski International School of Chicago. She also facilitates two extracurricular clubs that emphasize social and emotional learning, creativity, and STEM skills.

About our First Person series:

First Person is where Chalkbeat features personal essays by educators, students, parents, and others trying to improve public education. Read our submission guidelines here.