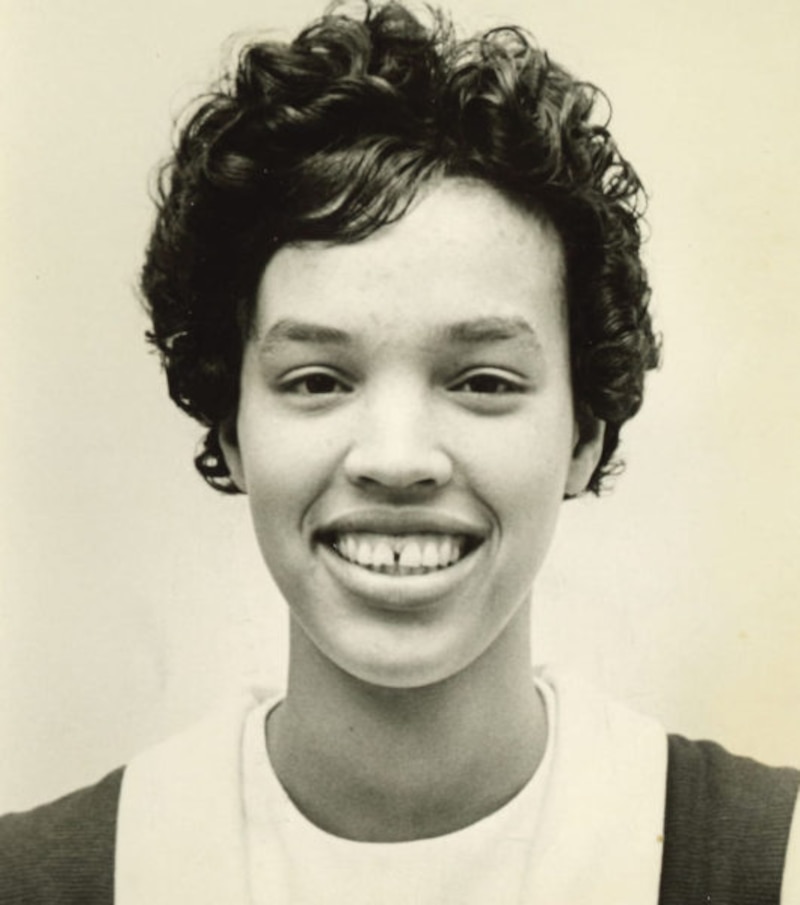

Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle hopes that teachers show up in force for her on Election Day Tuesday.

“First of all, I’m a member of the tribe,” said Preckwinkle, referencing her years as a teacher, which were largely spent in parochial schools. “I’ve spent my public life trying to transform neighborhoods and institutions, and I think that’s something teachers can appreciate.”

Yet the Chicago Teachers Union’s pick for mayor faces a major challenge in surprise frontrunner Lightfoot, who polls show leading Preckwinkle by double digits. In a phone interview with Chalkbeat Wednesday, less than a week to go before the April 2 runoff, Preckwinkle again made the case for why she’s the best choice for school-minded voters. (Chalkbeat has made multiple requests to speak with Lightfoot during the runoff campaign, but she has issued only emailed statements. Here’s what she told us in the weeks leading up to the February election.)

Preckwinkle mostly stuck to her talking points around investing in neighborhood schools, pressing for an elected school board and enacting a moratorium on school closings. But the former teacher also emphasized her stance on policing and the need for more oversight over charter and contract schools that serve the district’s most at-risk students.

Below is a transcript of the conversation with Chalkbeat’s Cassie Walker Burke and Adeshina Emmanuel, edited for brevity and clarity.

In its next contract, the Chicago Teachers Union is proposing a 5 percent salary increase. Yet CPS school budgets that came out this week account for half of that for next school year. Would you hold firm on a 2.5 percent raise, or be open to negotiating for more?

I’m not going to talk about my negotiating strategy with any of our labor unions to the press before we sit down at the negotiating table. I don’t think that makes sense.

What would you say to people who have concerns that you’re the union-backed candidate, and that the city still needs firmer financial footing — how can we trust you to negotiate on behalf of taxpayers and not on behalf of the union that supported you?

I was elected in 2010 with support from the labor union movement, and the first thing I had to do was lay off 1,500 people, many of them union members. That’s what we did because that’s what we had to do to balance the budget. I’ve been willing to make the hard decisions that need to be made, and I will continue to do that. The first consideration has to be what’s in the best interest of the taxpayers.

You have said you support an elected school board and would push for a bill to change how the Chicago school board is selected in Springfield. What campaign finance policies will you recommend for use in school board elections?

The same ones that apply to every other elected office.

Can you be specific?

There are campaign contribution limits, and other restrictions for those who run for city office, and those should apply as well to those who run for the school board.

But some people fear school board elections resembling what our political process looks like now in some ways, in terms of there being people who can pay for themselves to run for office, or get a member of their family to, or who align with certain special interests, or with unions. How would you want this board election process to be structured in light of that criticism so that it truly represents the community? Is there anything specific?

Those are broader challenges in our democracy. But I think democracy is better than the alternative, which is that the Board of Education is a creature of the mayor. I think it’s better to have an elected school board.

If academic gains started to taper off, if we started to see test scores or graduation rates decline, would you take that responsibility?

Here’s the thing: I think we’ve made progress, we’ve had some real challenges, not the least of which has been [leadership turnover.] (Editor’s note: Chicago has seen five CEOs since 2010, not counting two interim school chiefs.) We haven’t had the stability of leadership in in our public school system, and I think that’s been a real challenge. And that’s with mayoral appointments, which can’t be laid at the feet of an electoral process. I think there are always going to be challenges, but I think more democracy is better than less.

Would you still want to pick the school CEO rather than leave that to the elected board?

Normally a school board is responsible for picking leadership.

You would advocate that the school board take that responsibility?

Yes.

We took a poll of readers a few weeks ago, and many of them who identified as educators said they were largely undecided in this race. Why would a teacher or educator in the system vote for you?

I’m a teacher by profession, and I’ve spent my life in public service, as teachers do. Working for not-for-profit organizations, working in government, serving as alderman of the fourth ward and then Cook County Board president. I’ve spent my public life trying to transform neighborhoods and institutions, and I think that’s something teachers can appreciate, as well as the work I’ve done as county board president to increase access and improve the quality of health care delivered to our residents and increase the fairness in our criminal justice system by reducing the reliance on cash bonds, which basically penalize people for being poor.

One common question we heard in our survey: Why would you keep on Janice Jackson as CEO given some of the lapses in the way the district handled special education when she was the No. 2 at the district and ongoing complaints about how the district has handled sexual assault cases?

I proposed a very aggressive reform agenda: an elected school board, moratorium on school closings and on new charters, and I intend to work with Jackson on that agenda, and hopefully that’s an agenda she’s committed to and we can move forward.

CPS school-by-school budgets released this week channel $31 million in new equity payments to 200 schools with declining enrollment. Is it a wise use of taxpayer dollars to spend, for example, nearly $2 million to prop up Hirsch High School, which has 80 students in a building built for more than 1,000?

Well, here’s the challenge: Five years ago, CPS closed 50 schools in one year, and they were almost all in the African-American community. That’s a very public withdrawal of resources from neighborhoods. WBEZ reported that 38 of those schools are still vacant, and this is five years later. So to the young people who live in those communities, walk by those schools every day on their way to their new schools, and the adults who drive by, it continues to be kind of an open wound in most neighborhoods.

Furthermore, the University of Chicago did research on the young people whose schools were closed and who were moved to adjacent neighborhood schools, and they found that those schools were just as under-resourced as the schools they left, and that frankly, what happened was the achievement gap between black and majority students got magnified. I’ve said we need a moratorium right now on school closings as we look closely at these issues. We need to invest more in schools in neighborhoods where there is great need, and we shouldn’t rely on simply a per-pupil formula allocation.

Chicago put a moratorium on closings for five years, but didn’t solve any root problems that led to closings, such as enrollment declines. What would happen during your moratorium?

I think we would have to do a case-by-case, school-by-school analysis of what resources are needed to make the school successful, and to attract more students. The fact that young people in the schools that were closed went to adjacent schools where they were just as under-resourced as the schools they left, and that achievement gaps were magnified, should give us pause about school closures.

The next mayor will have to reform Chicago’s police department under a federal consent decree that will also have a big impact on police who work in schools, including their training and their job descriptions. What is one rule that you would want included in the agreement between CPS and CPD that will outline the role of police in schools?

I haven’t said that what we need is police in schools. We need security in schools, but I’m not sure about police officers. I will tell you that a concern to me, and I’ve been grateful for Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx in this regard, what concerns me is that when I was a teacher and things happened in the schools, kids got in fights or whatever, but internal challenges were always dealt with internally. We didn’t send kids into the criminal justice system for fighting in school. I think we have to be very careful about the presence of police officers in schools. We don’t want students to feel as if our schools are detention centers. We end up turning our internal discipline problems into criminal justice issues. That’s the danger.

So would you push to have fewer police in schools — or abolish them in schools entirely?

This is an issue we have to look at. We need security in many of our schools, undoubtedly, but the question is do we need police officers, and does the presence of police officers impact young people’s perception of their learning environment? They’re not detainees, they’re students.

Growing up in St. Paul, Minnesota, you were one of only few black students in a majority white high school. How did that experience shape or influence your view of public education?

I grew up on the north end of the city. It was a white working-class community mostly, with a few African-American families. I did pretty well in high school without having to work very hard, which didn’t happen when I got to college. (Laughs)

But looking back on it, our city faced some of the same challenges Chicago does in terms of the disparities between the opportunities available to students in the more privileged parts of the city and the opportunities available to students in the remainder. There were high schools we knew were better resourced than ours, but only as an adult, and in retrospect, did I realize the magnitude of the disparities and what that might have meant for students who weren’t as lucky as I was to get a scholarship to the University of Chicago and find opportunity elsewhere.

Outside of the city’s test-in schools, many of Chicago high schools are majority black or majority Latino. They are segregated, in a time where research tells us that diversity is linked to academic gains. Would you support the opening of more selective enrollment schools, which are popular with families? Why or why not?

I think we have to concentrate resources on our neighborhood schools. The problem with selective enrollment schools is exactly that — they’re selective enrollment. We need to have neighborhood high schools that serve all of our young people, that are well resourced, because they take every young person.

How do we balance the logic of integration with these facts: the district has struggled to attract white families and is largely black and brown with many schools predominantly one or the other?

I think the first priority has to be that the schools are well resourced. While I know there’s research that shows schools that are more integrated do better, given the magnitude and depth of residential segregation in the city, trying to ensure that every child goes to an integrated school is pretty much impossible.

Over the next few school years, CPS will pay between $600 million and $700 million for teachers pensions and the state will offset another $200 million. CPS has also borrowed a lot of money from the bond market to pay for buildings and wrestle with its debt. Beyond asking for more money from the state, What is something you would do to improve the district’s financial footing?

We need to work with the state legislature to incorporate our Chicago teachers into the state pension program. We pay for our teachers’ pensions, but we also pay for the teachers in the rest of the state, but they don’t pay for our pensions. We need one system that provides pensions for teachers, and Chicago Teachers Union should be part of that.

The second this is — we have to unwind a number of the TIFs. (Editors note: TIFs are tax increment finance districts, a funding tool meant to promote private and public investment across the city that has been criticized as inequitable). Right now a third of our property tax revenues go into TIF districts, these geographically sequestered funds. And much of downtown is in TIF districts, and that doesn’t make sense, because this is supposed to be an economic development tool, and instead we’re using this incentive in the most valuable real estate in the city, so that doesn’t make any sense.

Former State Rep. Barbara Flynn Currie had a proposal that, as we close down TIFs and declare TIF surplus, that all of that would go to public schools. What presently happens is it’s divided up between the taxing bodies.

Another thing we need to examine is workers’ comp. The county has 22,000 employees and spends $20 million on workers’ comp — the city has 35,000 employees and spends $100 million on workers’ comp.

And the next thing: Frankly, you have to bring in the department heads and tell them we have to make cuts, and they need to figure out how to do that with as little impact on programs and services as possible. There’s no magic solution or silver bullet, it’s just as lot of hard work — and it’s work that I’ve done before. When I came into office (at the Cook County board), the county had a $487 million budget gap to close. We looked first for efficiencies, told all the elected officials they had to cut their budgets by 15 percent, we refinanced some of our debt, and laid off 1,500 people. We made very difficult decisions we had to make to balance the budget.

Would you take a look at CPS’ headcount in the central office?

I think you have to look at everything, including headcounts in the central office.

But you also have to look at contracting. I’ve heard a lot as I’ve gone to schools about the contracts we have for keeping the schools clean, and how that’s not working, and we’re spending a lot of money on it.

Would that be something you would revisit, the janitorial contracts with Sodexo and Aramark?

Yes.

The school district has about 30 options or “alternative” schools for some of its most at-risk students. All but four of them are run by charter or contract schools — and there are serious questions about the quality of instruction. Does the district need to take a more hands-on approach?

The one that I’m most familiar with is the Alternative Schools Network, and that’s a longstanding not-for-profit organization that has run alternative high schools. I can’t tell you about the others, I’m not as familiar with them. But ASN has done good work for decades, providing alternatives to young people either pushed out of neighborhoods schools or who don’t feel comfortable there or whatever. But I think we have to be very careful. I don’t want us to be in a situation where we’ve created sort of a second-class high school platform for young people as opposed to our neighborhood schools and our magnets and selective enrollment schools.

But do you think the district needs to take a more hands-on approach?

The district has to exercise proper oversight, not just over charters, but over the alternative high schools with which it contracts. I’ve been critical of the district for closing neighborhood schools while at the same time not looking closely at the performance of charter schools, and there’s a broad spectrum of performance for those schools.

Mayor Emanuel has made supporting principals a big piece of his agenda, and Janice Jackson has followed suit, but we’ve heard concerns that principals have too much autonomy. Is that something you would take a second look at?

Principals are the leaders of their schools, and they have to have the discretion to run those schools well, and they have to be held accountable for performance and what happens in their daily work. The discretion is good, but it has to be accompanied by accountability.