When Jesus “Chuy” Garcia and Mayor Rahm Emanuel entered a contentious runoff for Chicago mayor in 2015, the powerful Chicago Teachers Union invested more than $420,000 in Garcia.

In this year’s mayoral runoff, it has ponied up little more than a quarter of that to back County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, a former teacher who was considered a front-runner early on but has trailed in the polls.

But no one at the union’s modern Near West Side headquarters seems that worried that their candidate might lose to former federal prosecutor Lori Lightfoot.

“I feel like we have already won,” said Stacy Davis Gates, the group’s vice-president, who counts as a victory the propulsion of two black women who support one of her group’s most cherished causes — an elected school board — to the runoff.

“Our movement continues to transform the electorate in Chicago.”

The teachers union hasn’t sat out the mayor’s race completely. Beyond funding her opponent, the union has derided Lightfoot via email and social media as a corporate lawyer and pseudo-progressive appointed by Chicago mayors, and backed by some of the same corporate funders as Emanuel, the union’s longtime adversary.

Related: Here’s why Toni Preckwinkle thinks she’s the best mayor for Chicago schools

But with the serious possibility that their candidate loses, the union is also focusing its energy on battlefronts beyond City Hall— fights that could be critical for its survival and success. It has pushed bills in the state Capitol that would bolster its power at the bargaining table over non-salary issues like class size and staffing, threatened strikes on behalf of its newest recruits — educators at 13 charter and contract schools — and bargained with Janice Jackson’s administration for some 24,000 teachers at district-run schools. On that front, it’s been warning members to start saving money for a potential strike, too.

While the union’s approach might seem too scattered, public-sector union expert Julia Koppich said that “they may just be pursuing the same goals on multiple fronts,” particularly in light of last year’s Supreme Court decision outlawing mandatory union fees for non-union members. The ruling, commonly known as Janus for its plaintiff, has been viewed as a blow to union power.

“They don’t have the luxury of saying we’re simply going to try to negotiate a contract with the school district and that’s the end of what we do,” said Koppich, a San Francisco-based consultant. “Unions are faced with having to give members a reason to pay dues, a reason to belong, and there are so many different members who have so many different issues and interests.”

Related: Another wave of charter strikes: Teachers at five Chicago schools announce dates to vote on walkouts

The union’s leadership also faces an internal challenge. Members First, a caucus running to replace the current leadership in May union elections, said it’s fed up with the time and resources the union spends on what it views as non-school issues and political causes, and is vying to focus the union solely on protecting members and bargaining for better wages, benefits, and working conditions.

Davis Gates disagrees with the idea that the union is spreading itself too thin.

“We believe in interdisciplinary work,” she said, “like all good teachers do.”

The union’s case for Preckwinkle

The union endorsed Preckwinkle in December, considering her its surest shot at a progressive mayor willing to back an elected school board among a crowded field with well-known candidates like Bill Daley and Susana Mendoza more at odds with the union’s positions. The union also touted Preckwinkle’s record as Cook County president overseeing health insurance expansion and reducing the county jail population.

But even before the runoff, the union’s candidate met obstacles in her past association with longtime machine politicians like former Cook County Assessor Joe Berrios — who was accused of nepotism and corruption for years, and of erroneous property tax assessments that unfairly burdened homeowners — and Ald. Ed Burke. Burke, under federal investigation, faces one count of attempted extortion.

In the runoff, Lightfoot gathered endorsements, including from former school board president Gery Chico and one-time schools chief Paul Vallas, two figures the union viewed as problematic.

Related: Preckwinkle vs. Lightfoot: Differences emerge in how mayoral candidates would govern schools

Erica Meiners, a professor of education and gender studies at Northeastern Illinois University, sees union support of Preckwinkle early in the race as a harm reduction strategy.

“I often think about legislative and electoral politics as a form of harm reduction. How can we make decisions — or pick candidates — that will do the least amount of harm?” she said. “It’s not where we always make the ideological gains we want, or win hearts and minds.”

“We are going to continue to to fight.”

After the Janus ruling, labor experts predicted the teachers union would need to redouble recruitment and make the case to members for paying union dues.

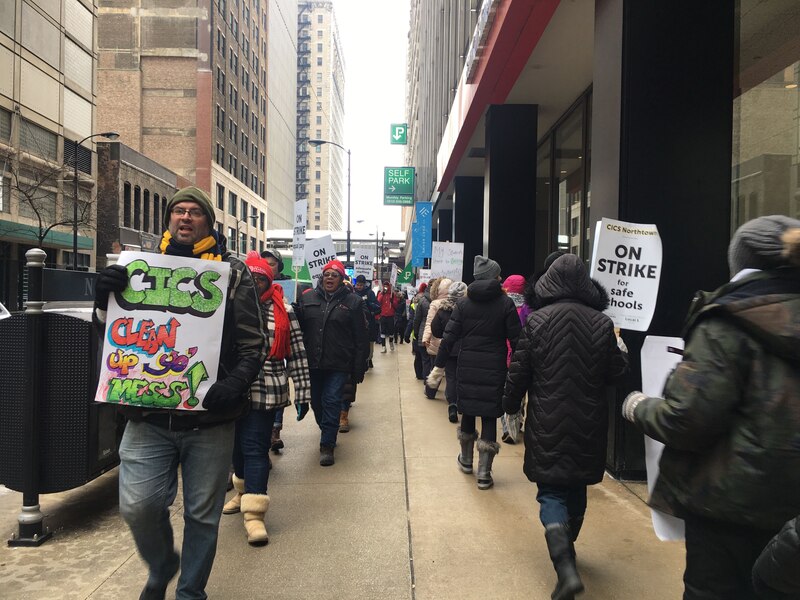

To bolster membership, Chicago’s union has beefed up action at charter schools. It has orchestrated two strikes that won key concessions from Acero Schools Chicago and four schools under the Chicago International Charter Schools umbrella. It is currently bargaining with seven operators of 13 other charter and contract schools and threatened to strike against several, including ChiArts and Instituto.

Now it’s heading into negotiations with Chicago Public Schools on behalf of its 24,000 district members.

Gates said the union plans to hold the next mayor accountable, and to take a hard line on contract negotiations with the city. In an email earlier this month, union President Jesse Sharkey advised members to save 10 percent of their checks in the case of a strike early next school year.

Related: Election aside, Chicago Teachers Union talks strike on two fronts

A cordial relationship would benefit both parties and students as well, said Robert Bruno, director of the labor education program at the University of Illinois.

“The teachers can’t do this without somebody in the mayor’s office who is fully supportive and is helping put funds in the right direction,” he said. “And the mayor can’t be successful without school improvement, [and] if the people who work in that school district are not feeling genuinely respected and provided resources they need.”

While the union hasn’t come out with as much vitriol for Lightfoot as for Mayor Emanuel, there’s a big possibility that the candidate they’ve painted as the closest thing to him could be the one they encounter at the negotiating table. Davis Gates brushed off concerns about potentially souring the union’s relationship with Lightfoot.

“Our militancy,” Davis Gates said, “is not dictated by who sits on the fifth floor of City Hall.” So far, Lightfoot hasn’t fired back at the union, and like Preckwinkle, won’t divulge her bargaining strategy before negotiations begin.

Perhaps staying mum is a wise strategy, said Kyle Westbrook, who formerly advised Emanuel on education. With tough talk, the mayor “created a lot of bad blood, it didn’t create the right environment for real negotiations,” he said.

The union’s pattern of “conflating issues,” such as tying school closings and other policies to gentrification and disinvestment, also didn’t help, Westbrook said.

Related: The tension between Chicago enrollment declines and new schools

The union insists grappling with the forces of economic and racial inequity that Davis Gates said are pushing out many black families and heightening an enrollment crisis are part of its mission.

“All over this country, teachers have been very clear about asking for resources for their classroom, to be able to afford to live in the spaces where they reside,” Davis Gates said. “Chicago has helped to lead the way in that fight — and I don’t see how that changes.”

CTU elections are scheduled May 17, the same week the new mayor will be sworn in.

Use the tool below to compare Preckwinkle and Lightfoot’s answers to our January voters guide questionnaire.