The high school anime club was her idea. But when the moment came to log in on a recent Thursday evening, Demaya Holman hesitated.

Fitful sleep the night before and the daily gauntlet of online classes had left the freshman at Chicago’s Englewood STEM High School feeling drained.

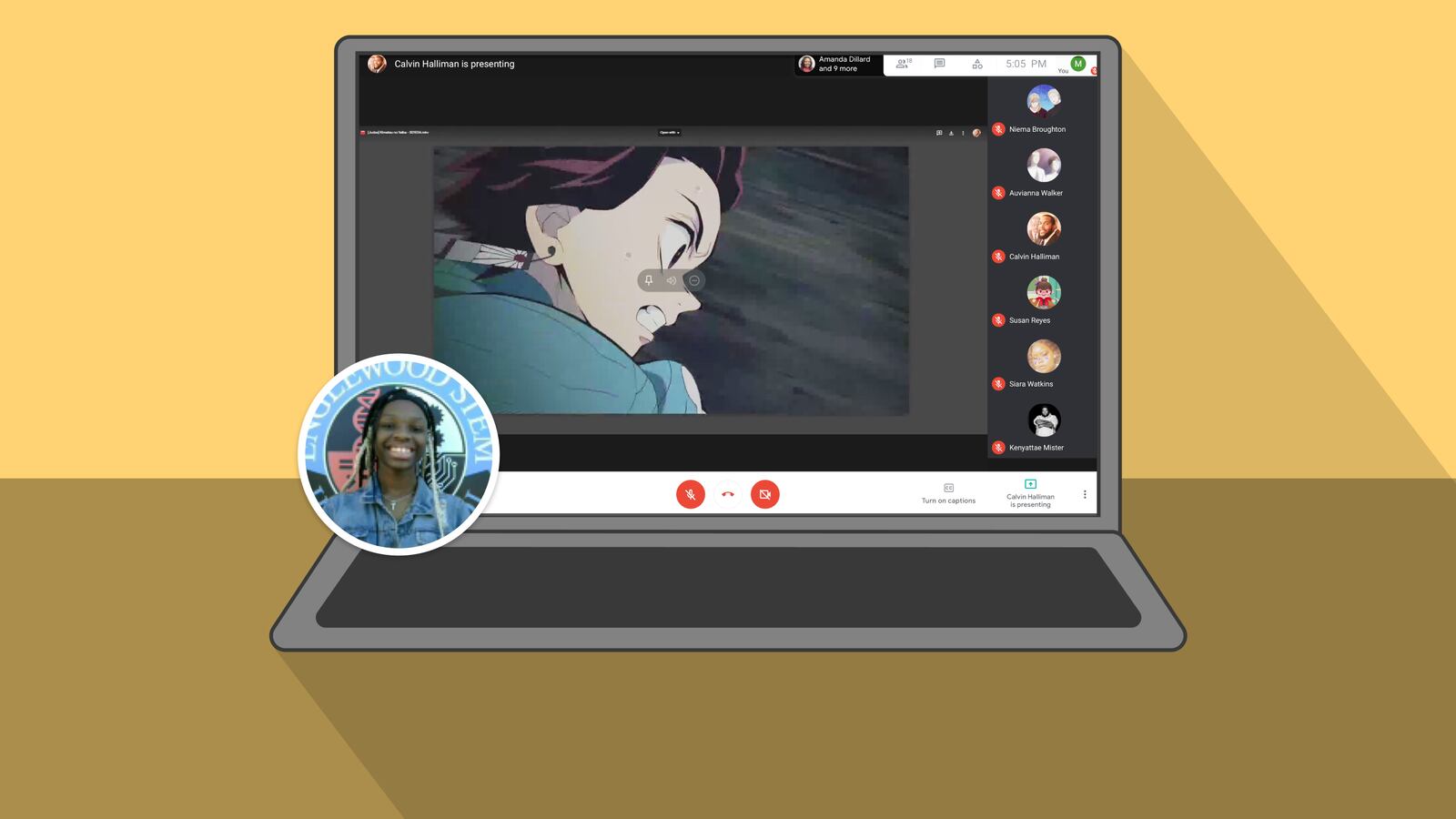

As dusk fell outside the windows of her living room, she balked at firing up yet another Google Meet on her school-issued Chromebook. Demaya had started the club, transplanting her passion for Japanese animation to the corner of the web her high school occupies this fall.

Now, two months into the school year, she had to acknowledge the club had not turned out exactly how she’d imagined it.

Demaya arrived at Englewood STEM this September, unfazed to be the new kid at a new school. She tackled with gusto that all-important transition to high school, made more treacherous by the pandemic’s disruption. Her school, which opened its gleaming $85 million campus in 2019 after deeply contentious school closures, was still at work chipping away at community mistrust and building up its own culture.

This summer, on the cusp of an unprecedented school year, Englewood STEM’s leaders set a goal of steering more students toward clubs and other after-school activities. It’s a research-backed strategy to foster academic engagement, but also a bid to forge ties among students marooned in their living rooms, especially crucial in a neighborhood hard hit by the coronavirus and relentless gun violence this year.

Demaya came determined to foster just such a sense of connectedness — to reach out, speak up, be “an open book.” And what better way to rally like-minded classmates than through her favorite anime shows, which — with their somber storylines but crisp, clear-cut messages — had sustained her through the uncertainty of 2020?

“Watching anime during a time like this is one of the best things you can do,” Demaya said. “It tells a story. And everybody loves a story on dark days.”

That evening of the club meeting, she hesitated only slightly: She logged on to the club.

When Demaya’s icon popped up on the Google Meet screen, there were about 20 fellow students already waiting. Like her, they all had their cameras off and microphones on mute. Demaya’s avatar was a character from the series “Tokyo Ghoul,” a girl who, as Demaya puts it, “went through a lot of conflict, which was bewitching.”

Calvin Halliman, one of the club’s faculty supervisors, typed the name of the first show in the chat box, cued it up and — without a preamble or chit-chat — anime club was underway. Watching silently with peers tucked behind their own anime avatars, Demaya was pulled into a battle between characters caught in fierce hand-to-hand combat somewhere in Japan.

At the start of the school year, Demaya had planned to email Englewood STEM’s principal, Conrad Timbers-Ausar, about her club idea. Then, a week in, the school held the first of its regular “community” rallies for students, whisked from the school’s gym to the web. Timbers-Ausar gave a pep talk and introduced faculty and staff before inviting students to speak. The silence that followed was becoming awkward when Demaya unmuted herself.

“I was wondering if it would be completely all right if I am the founder of an anime club?” she asked.

Impressed with her gumption, the principal told her that was certainly all right — if she could enlist a faculty supervisor and recruit students. In the chat box, four other freshmen said they were in.

Demaya had graduated from the neighborhood’s Kershaw Elementary, where, like at Englewood STEM, the student body is predominantly Black and roughly 90% of students qualify for subsidized lunch.

At her virtual middle school graduation, Demaya won an award for citizenship, honoring students who participate actively in classes or community service. She stopped by the school and posed in a sparkly yellow cap and gown and white face mask under a balloon arch, her principal leaning in to hand her a diploma from six feet away.

In a city with intense competition for high school seats where South Side families have long argued they have fewer high-quality choices, Demaya had wanted to attend Dyett High School for the Arts. She worships Maya Angelou and dreams of becoming a writer or poet — or failing that, a counselor or therapist, cautioning people against “bottling things up inside.”

But she says Englewood STEM was a close second choice. They have a great arts teacher. She wanted to stay positive.

“You are creating your school life the way you choose to make it,” she told herself.

Englewood STEM opened its doors last year as the district phased out four neighborhood schools amid intense community opposition and charges that chronic disinvestment had doomed those campuses. Anger and mistrust lingered, with some residents predicting the school would recruit students from outside the neighborhood and displace local teens.

Timbers-Ausar said he understands these sentiments: “Those high schools were a part of who people are. It felt like shutting down a part of you.”

He rattles off numbers from the school’s first year to make a case that Englewood STEM is delivering on district promises. More than 95% of students enrolled from within the neighborhood boundaries. More than 90% of freshmen were on track academically at the end of that first semester — a closely watched metric that Chicago researchers have found is a key harbinger of high school completion.

This year, Englewood STEM’s second, presented its steepest challenge yet: how to continue to build a sense of connectedness virtually, against a backdrop of a virus that has claimed Black lives disproportionately and during a painful national reckoning on race and racism.

The school leaned on those virtual “community” rallies, where students together processed the decision not to charge Louisville police officers for Breonna Taylor’s killing and pushed back against some teachers’ mandate to keep computer cameras on during digital classes.

Then there was the new push to promote clubs. The school boasts 15 of them this year, from chess to journalism to an e-sports club whose members are so fired up that they meet every weekday afternoon. The school sends out a weekly “club blast” over email and on social media to nudge students to log on.

Demaya had a vision for the anime club. Members would watch a show and discuss the themes and characters. They would have weekly activities to immerse themselves in Japanese culture: making origami, or preparing sushi or rice bowls together.

Anime club would be an accepting, tight-knit space, a salve for the vagaries of the tense global moment. The show “Naruto” came to Demaya’s mind, in which the striving protagonist stands up for shier, weaker kids in ninja school.

“Never allow your peers to go it alone,” as Demaya summed up the show’s takeaway. “Everybody needs support.”

The first anime club show was over that Thursday. Halliman typed a reminder to sign the club’s attendance sheet and cued up the next show, “Mushi-Shi.” Demaya had recommended the series: set in 18th- or 19th-century Japan, about mysterious organisms that cause life-threatening afflictions. The artwork was beautiful. The story was dark. At one point, an entire village is felled by illness.

But to Demaya, it was a darkness in which she was entertained, not tested or flailing — a safe emotional rollercoaster for a change.

Through the first months of the school year, Demaya has maintained an enviable focus on her studies, said Amanda Dillard, one of Englewood STEM’s counselors. She reaches out when she runs into hurdles, such as the internet connectivity issues that have plagued students this fall.

Demaya nods to the challenges of this uncommon fall, but she’s not ready to be a completely open book. She speaks simply of “outside occurrences that affect my emotional state.”

What matters is that she is learning to cope: “I take a breather. I let it go.”

The first meeting of the anime club back in October had been a highlight. Students debated which shows to watch and how to structure meetings. Almost 45 had signed up.

Then, the club lapsed into a routine of watching shows quietly, the students receding behind impassive rectangles on the familiar Google Meet grid. Occasionally, they lingered and chatted briefly at the end. Other times, everyone would log off as soon as the last show’s credits rolled.

“In person, the students typically would sit with their friends and talk, or sometimes you get collective gasps when something happens in a show — difficult to really do that remotely,” Halliman said.

The sense of connectedness the school is working to foster can be elusive. Last month, not one freshman logged on to the latest “community” rally. In the school year’s second quarter, the event moved from Friday afternoons, when signing on to one more Google Meet might be a hard sell, to Wednesdays.

One day, when Demaya and her classmates are back in the school building, she will pitch some changes to anime club: not as much show-watching, more discussion, more cultural activities. It’s unclear when this might be: District leaders are planning a return for younger students in early 2021, but they haven’t set even a tentative date for a high school comeback.

For now, the club’s format — that quiet communion with beloved stories — works just fine.

That Thursday evening after the final show, Halliman turned on his camera and urged students to share ideas for new shows in a virtual suggestion box. But instead, the teens took to the chat box, which came alive with anime series names and comments.

For at least a moment, the distance separating them was shortened.