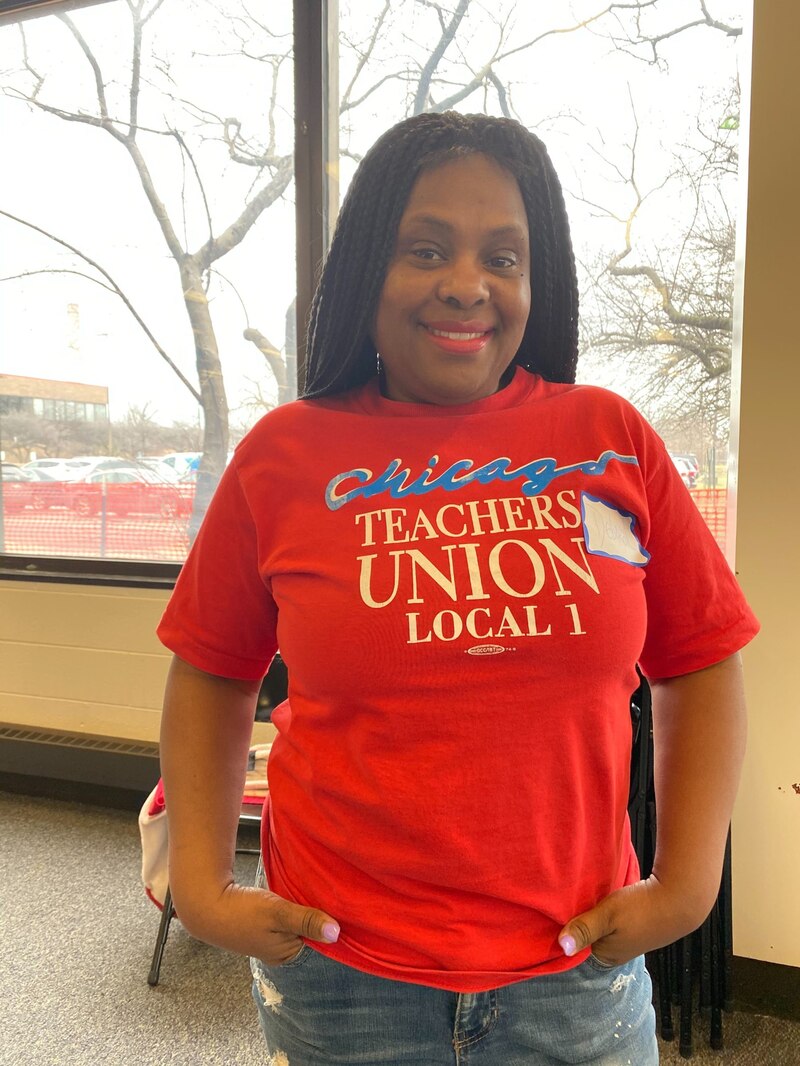

Arnette McKinney arrived at a recent Chicago Public Schools budget workshop armed with a written list of items she wanted to be funded in public schools across the city: a gym, better arts programs, and a more robust library, to name a few.

“Where’s the librarian, where’s the music teacher?” asked McKinney, a parent at Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center School and a teacher at Fiske Elementary in Woodlawn, echoing a frequent question that has surfaced at hearings about how Chicago funds its schools.

At Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s urging, Chicago Public Schools held six workshops to solicit public feedback on school funding, a complicated topic in a city that spends more than $7 billion on education but steers about half that to its individual campuses (the rest goes to charters, pensions, capital expenses, citywide and network level support, and central office administration).

Meetings were wide-ranging, with educators, parents, and community members offering up suggestions in front of district officials. But the district has provided little clarity about promised changes and how public comment to influence them.

“We actually want to earn public trust in a very honest way,” said Maurice Swinney, chief equity officer for Chicago public schools, at a hearing at Corliss High School. “How do we keep these movements and conversations going? … What are the definitions and formulas we need to put out so people can see how we’re making decisions?”

A 29-member funding commission will recommend how the Chicago school board could change its school funding formula.

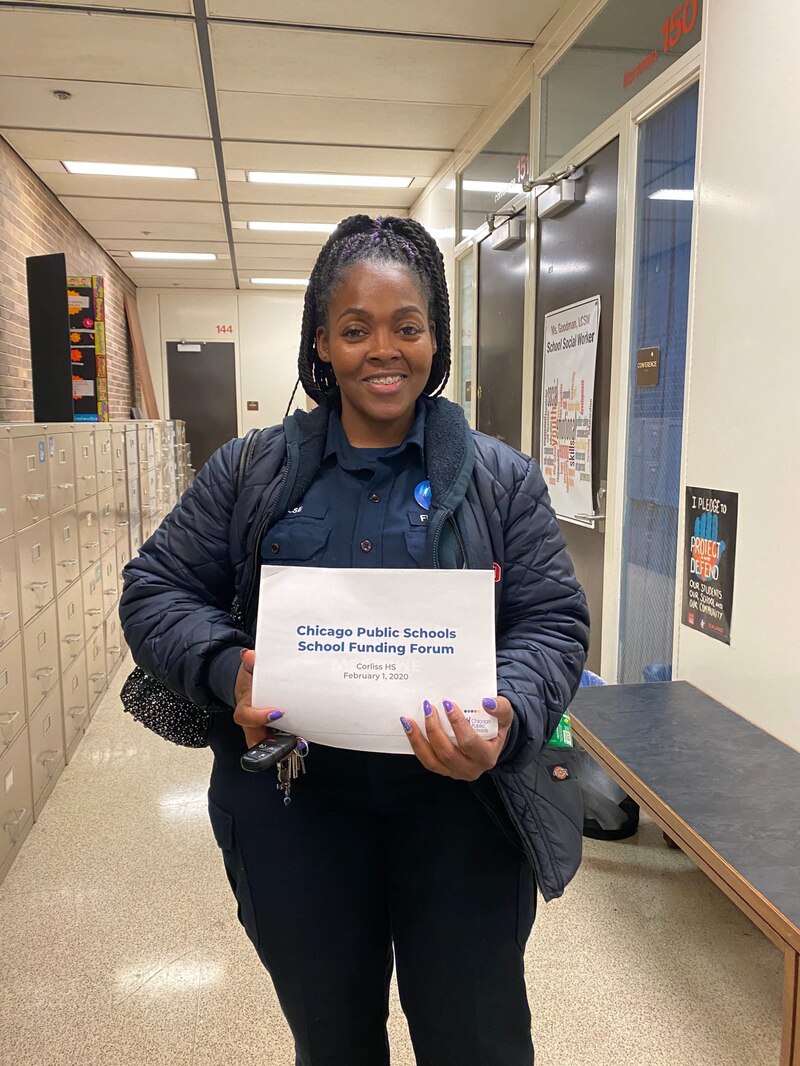

But what if parents and teachers had the pursestrings? Chalkbeat spoke to several at the Corliss hearing in the city’s Pullman neighborhood, to find out what they’d prioritize.

McKinney (pictured above) said her school, Fiske Elementary, has an art program that it funded by a foundation run by the Chicago hip-hop artist Chance the Rapper. But the school has no music program.

“I believe our schools should have the same funding, it shouldn’t be more on the North or more on the South, it should be equal,” McKinney said. “Those that are underserved should be brought up to the standard of everyone else.”

McKinney also said she’d like to see funding for a parent mentoring program at Fiske. Parents may qualify for a stipend only after they’ve volunteered 100 hours for the program, she said.

Pearlena Mitchell, also a teacher at Fiske, said that schools should be funded based on individual needs of students, rather than all schools getting a flat rate, and parents should be able to see where the funding goes.

“One size doesn’t fit all,” Mitchell said.

CPS parents Rodneyka Armstrong, left, and Alexis Mimms, whose children also attend Fiske Elementary, want more resources for extracurricular activities to keep students engaged during and after school.

“Extracurricular activities for the kids, football, basketball and after-school programming, like tutoring,” she said, “it’s important because it gives children things to look forward to and things to keep them out of trouble. Children at the school are always saying how they wished they had football, basketball, things like that and tutoring for them.”

“My son gets bored very quickly, he just sits in his seat and does work all day,” Armstrong said. “They need to get out, stretch their arms. I think a science lab would be good.”

Brent Hamlet, a paraprofessional at CICS Bucktown, attended Chicago Public Schools and now works at a charter school managed by Distinctive Schools. A fellow with the education policy group Educators for Excellence, he said he attended the workshop to learn more about how funding is allocated and to share his insight from working in schools on both the South and North sides.

One of the issues he noticed at some schools was that the cadre of teachers did not reflect the diverse student body. He would like to see resources directed toward recruiting more teachers of color.

“How does staff reflect the community’s vision of the school and how does the staff reflect the student body?” he asked.

Deborah Riddel is a special education teacher at Charles W. Earle Stem Academy, where she said last year she had a packed classroom of 22 diverse learners. In some cases, her classroom is larger than the classrooms the students were pulled from, she said.

“I’m a special ed teacher and our students are not receiving what they need in resources,” Riddel said. “With special education, they need something extra or different and they don’t receive it … there should never have been 22 students in my classroom at one time, but my principal said there’s nothing we can do.”

Riddel said that many parents aren’t aware of their children’s rights. She suggested that the district provide an advocate to help bilingual students and students with disabilities at each school.

Additionally, the school system should fund additional social workers, case workers, advocates, and resources in schools in areas with high crime rates, she said.

“Some of these students are experiencing things like PTSD, depression — the things that they share with me you would not believe,” she said. “The area where I teach has the highest crime in the city. That means that those students are either related to the perpetrators or the victims in higher numbers than anybody else in Chicago. So we should be getting more [resources to help them], right?”

Tamara Helse is a parent who serves on the board of governors at Air Force Academy High School and the Local School Council at Harold Washington Elementary School in Burnside, where her children attend school. She said despite its designation as an arts school, Harold Washington doesn’t have a robust art program and she’d like to see more of the budget dedicated to that.