Thousands of education jobs around Illinois went unfilled last school year.

The 6,052 teaching and support vacancies signal a complicated problem that won’t be solved just by recruiting more college students, according to education experts. Instead, they said, the solution lies in making the profession more attractive, providing more support and funding across the board, improving teacher retention, and diversifying educators.

Warnings about the teacher shortage have reverberated around the state for years, but a new report released Wednesday from the policy group Advance Illinois offers insight and suggests possible remedies.

And while much of the focus in education is currently on stemming learning losses due to extended school closures and the coronavirus disruption, the discussion has started to turn to the future of in-person learning.

“The single most important thing we can give a child coming out of this pandemic is a quality teacher,” said Robin Steans, the president of Advance Illinois. “It has never mattered more.”

The pandemic has narrowed the window to legislate solutions to the teacher shortage, as well as intensified financial pressure on public education systems. But Steans said the teaching profession might draw renewed interest, as other industries shed jobs and workers seek new careers.

“I’ll be surprised if there aren’t some number of young people looking ahead who don’t set their sights on teaching,” she said. “What will be interesting is whether we take advantage of that and do it in a way that really increases diversity.”

Here are five things that stand out in Advance Illinois’ analysis.

- The state has lost half of its educator prep programs since 2012.

Teaching is a rewarding but difficult profession. More than 6,000 education positions around Illinois went unfilled last year, including instructional, administrative and support positions, but the policy fix won’t be as simple as recruiting more college students.

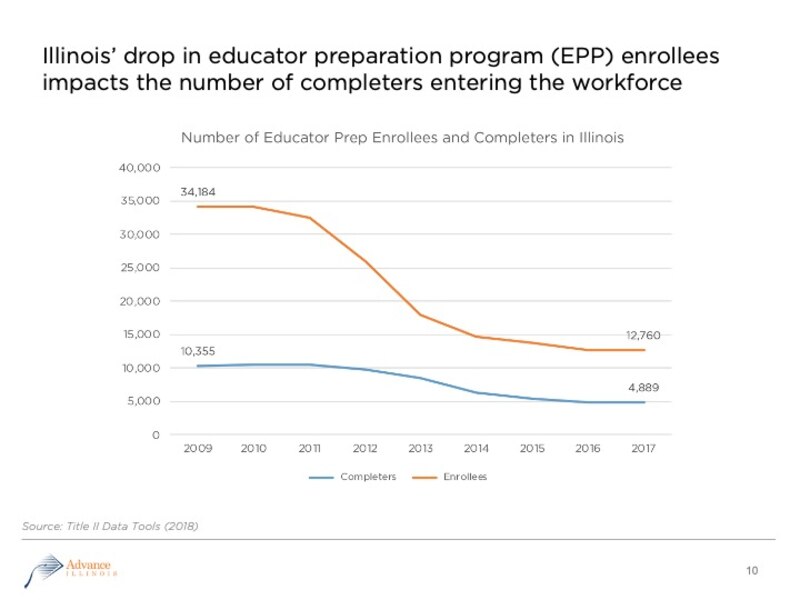

Since 2012, Illinois has seen a 50% decline in the number of graduates of education prep programs, as well as a decline in the number of teacher prep programs. Fewer programs has translated to fewer graduates: In 2012, there were 11,000 graduates. In 2017, there were just under 5,000, thus sending fewer teachers into the workforce.

“This is not just an interest problem,” said Ann Whalen, director of policy at Advance Illinois.

Research has shown that it matters where programs are located. Whalen noted that a majority of teacher candidates choose to teach near where they went to school or where they are from originally. In Illinois, nearly one in five districts is more than 30 miles from a teacher training program, hampering their ability to recruit student teachers and build pipelines to future educators.

Traditional training programs are particularly sparse in southeast Illinois, Whalen said. Alternative non-traditional certification programs are mostly located in Cook County. But even those have seen a decrease, dropping from 12 to six programs from 2008 to 2016.

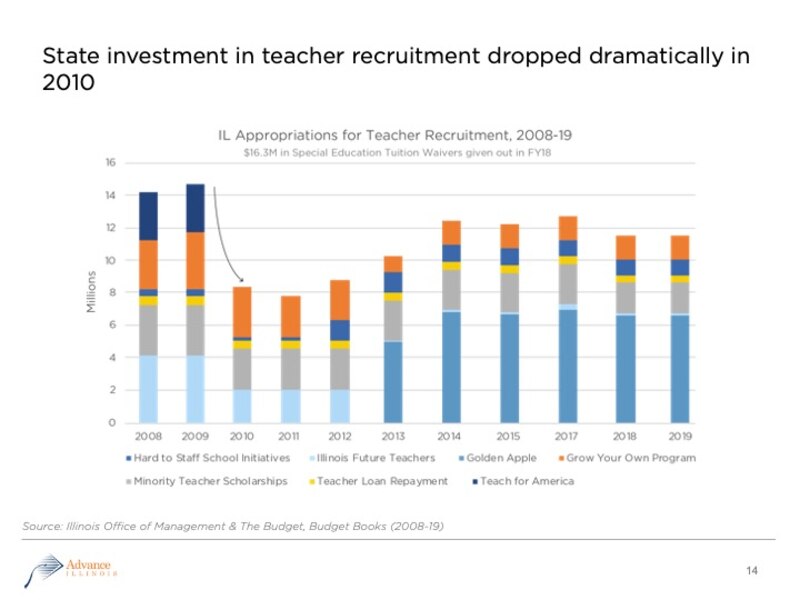

The decline is due in part to state disinvestment in that time period, Whalen said. According to information from the Illinois Office of Management, spending on teacher recruitment and financial assistance programs, including the Illinois Teacher Loan Repayment Program, Golden Apple tuition assistance and scholarship program, and minority teacher scholarships, has shrunk by more than $3 million since 2008.

“We need to ensure both our districts and our educational prep programs have the resources they need to support these candidates but also for teachers to grow and be retained by the profession,” said Helen Zhang, policy associate at Advance Illinois, who analyzed data from the Illinois State Board of Education, the census, and federal Title II reports on national teacher preparation.

“Maintaining the status quo isn’t going to be sufficient to get us out of where we are right now.”

2. The shortage is most acute in special education, followed by elementary education, bilingual education, and science, math and technology (STEM).

Linda Perales teaches reading and math special education to kindergarten, first and second graders — many of whom also require English and Spanish language instruction — at Corkery Elementary School in the Little Village neighborhood of Chicago.

The number of students in her classroom has fluctuated throughout the years, but reached a peak of 17 students. That’s small compared with a traditional classroom, but her students aren’t typical. She said it’s difficult to give each child the attention they need when she has a full classroom of students with different needs.

“I have to basically do the job of eight teachers,” Perales said. “The kids that need the most support are actually just getting a fraction of what they need because of the shortage … It’s a disservice to the students for sure and also unfair to the teachers who have to do way more.”

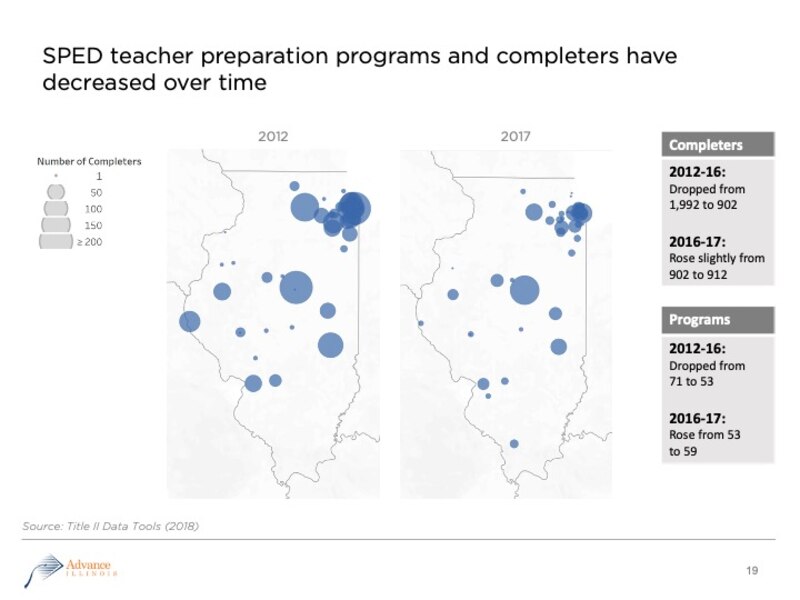

From 2012 to 2016 the number of special education teacher prep programs in Illinois dropped 25%; the number of bilingual education programs for aspiring teachers fell by half. The number of graduates from each specialty program likewise plummeted.

A similar trend happened with STEM preparation programs, which dropped by a third.

The numbers have started to inch back up. But the increase has not caught up to previous supply levels, and the need meanwhile has increased. In Illinois, the proportion of students in special education, as measured by those with Individualized Education Programs, has increased from 14% to 16% in the past five years. The share of English learner students has risen, too.

Perales said she believes fewer people are entering teaching because the profession is undervalued.

“A lot of people are not choosing teaching as a career because they know that it’s exhausting and they know that our profession is poorly respected, they know that we lack resources and that our schools are underfunded,” Perales said. “They know that they’re going to be overworked and underpaid.”

3. The state can’t tackle the teacher shortage without addressing teacher turnover.

For Kira Baker-Doyle, an associate professor and director of the University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Literacy, the slowdown in students entering teaching is exacerbated by a wave of older teachers retiring. Education experts have braced themselves for a national shortage for 30 years, she said, anticipating when baby boomer career teachers would retire and leave a multitude of unfilled positions.

According to the Illinois State Board of Education’s annual financial report, the number of retiring teachers peaked in 2017 and has been declining, but retiree counts still top 1,000 each year.

The losses aren’t just among older teachers.

Younger teachers are leaving the education field in search of higher-paying, less stressful opportunities, something that wasn’t as common in the past, Baker-Doyle said.

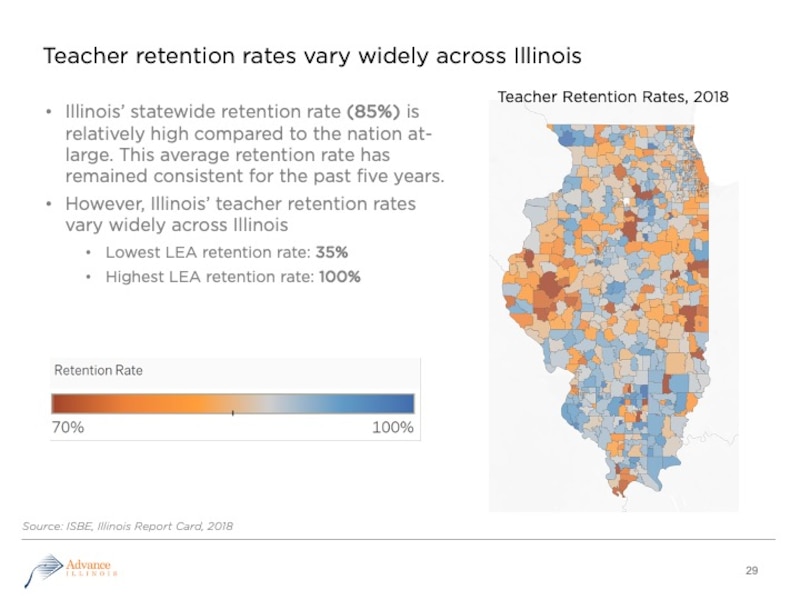

Across the country, turnover rates are highest among new teachers with less than three years experience. Statewide teacher retention rates have hovered around 85% for the last five years, but vary widely when broken down by district, from 35% to 100%, according to Illinois Report Card data.

With fewer teachers, the increased workload lands in the laps of the remaining teachers who then may be more likely to quit due to stress, said Catherine Main, an associate professor at University of Illinois at Chicago.

When a school can’t find a teacher, often it will rely on temporary employees to fill in. Main said her students report difficulty with having a succession of teacher assistants while they complete student teaching rotations in the classroom. Students entering the field won’t have trouble finding a job, she said, but many have already witnessed the pressure that the loss of teachers and teacher assistants puts on the remaining employees.

“People are excited that there are lots of [job] opportunities from the student perspective,” she said. “But on the flip side, there’s a lot of turnover in the workplace because of the shortage … it’s a vicious cycle.”

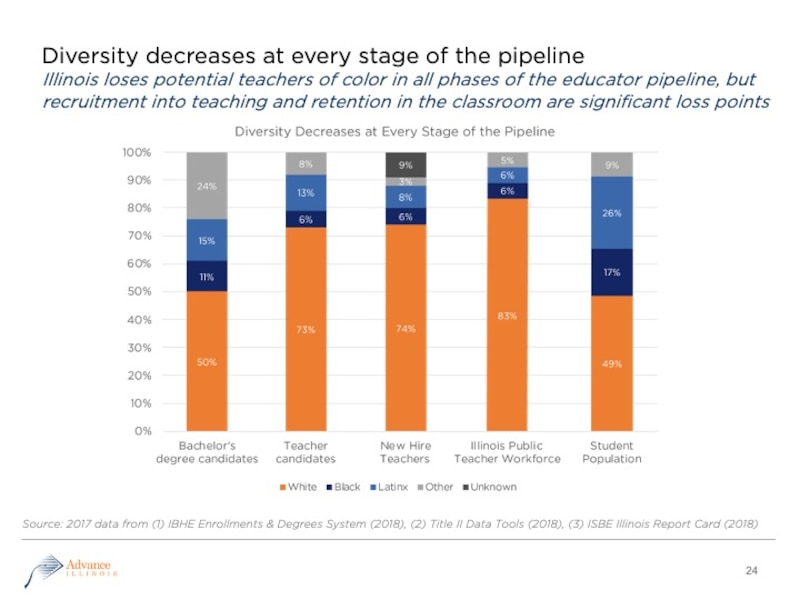

4. Teachers of color enter teacher prep programs but don’t end up getting hired.

Aspiring teachers of color are entering the teacher prep pipeline, but they’re not ending up in classrooms. Steans, of Advance Illinois, said policymakers need to focus on why.

Research has shown that teacher diversity affects many learning conditions and outcomes for students, including test scores, graduation rates, attendance and suspension rates.

About 50% of bachelor degree candidates are black, Latino, or non-white, but in Illinois, just one in four new hires is non-white.

There has been slight progress, the report notes, as Latino teachers have increased from 7% to 9% of new teachers in Illinois from 2013 to 2018.

“Every student in Illinois deserves skilled educators who reflect their diversity and are dedicated to challenging them academically and supporting their growth and development,” Zhang said. “These data make clear that not only are we not recruiting and graduating enough teachers of color, we are doing a poor job retaining them in the classroom. This is something our state needs to bring greater transparency to in order to ensure we are sufficiently addressing the need and targeting effective strategies.”

5. There’s not going to be a quick fix for the issue.

State leaders, including the governor, have acknowledged that the teacher shortage is a critical issue. That was before the coronavirus forced the shuttering of all school buildings in the state at least through the end of the school year and began squeezing state revenues.

Before the crisis, a change in the state funding formula and a boost in state spending on public schools allowed some districts to add teaching jobs. But some other approaches that would help with recruiting, such as prioritizing loan forgiveness programs and offering scholarships to early-career teachers, were slow to get off the ground.

What will happen now is unclear.

Pre-coronavirus enrollment numbers had slowed at Northeastern University, including among Latino and African American students in the education college, said Andrea Evans, interim dean of the Daniel L. Goodwin College of Education.

Some potential students may have decided to attend out-of-state schools that offer more student loan forgiveness, less costly housing, or higher supply stipends for early-career teachers, Evans said. Illinois’ dwindling support for higher education, which means oversaturated scholarships and programs that often don’t cover enough, may have also played a role.

“The entire education enterprise — federal, state, local — has to be willing to provide the types of professional development, financial, and social supports early-career educators need,” Evans said.

Solving the shortage will also require a cultural shift in how our society values teachers, she said.

“The public perception of the job may make it difficult to recruit students,” Evans said. “The manner in which we talk about teaching as a profession — challenging work environment, low pay, disrespect from parents, students, and/or administrators — can make it difficult to recruit talented students into the profession.”

But with broad shifts in the economy likely coming with the coronavirus pandemic, this could be a moment for renewed interest in the job. In a shrinking economy, Steans said, “there is a real chance that teaching will look more appealing than it did six months ago.”

Cassie Walker Burke contributed reporting.