With Chicago’s school police program under the microscope during a tense summer, Mayor Lori Lightfoot says the city now will put more strict protocols on which police officers serve on campuses and pull out school-based computer terminals that previously connected officers with centralized criminal databases.

Those changes are part of a slate of proposed new reforms announced Wednesday, nearly a year after Chicago Public Schools and the Chicago Police Department began complying with a federal mandate to address long-standing problems in the program. Officers last school year served on more than 70 campuses, with more mobile officers in cars assigned to schools.

A Chalkbeat Chicago investigation in February showed that six months after school police reforms were initially supposed to be implemented, they were still a work in progress, with many items on the list incomplete. Concerns over the program, and a perceived lack of oversight, helped fuel heated school council meetings this summer over whether or not to keep police on campus. In all, 55 councils voted to keep police and 17 voted to remove them.

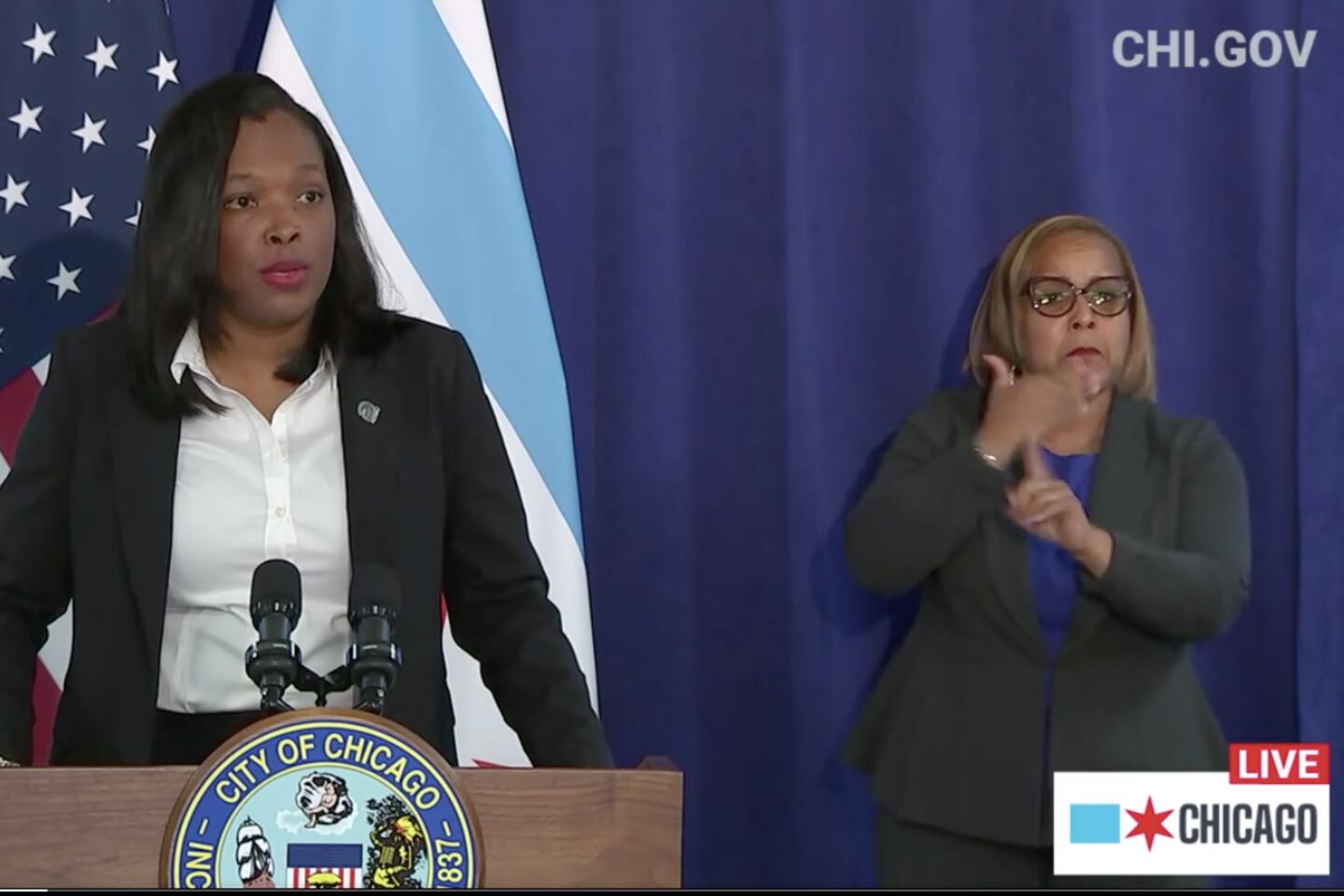

Lightfoot and schools chief Janice Jackson now say they are working with the city’s police department to address unresolved issues. Principals will now have the explicit power to hire or reject candidates for the jobs on their campuses — an authority that had been promised earlier but not uniformly delivered — and the city will partner with the Center for Childhood Resilience at Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and the student-focused organization Mikva Challenge to better train officers in how to work with youth.

Chicago will also set up a more formal complaint process that parents, students, and educators can follow in case of concerns about officer wrongdoing.

At several youth-led protests throughout the summer, several students described often fraught relationships with campus officers and how the presence of police made them feel targeted and brutalized in buildings where they were supposed to be learning.

“We have heard our students loud and clear. The reforms today are a direct result of their tenacious spirit,” said Jackson.

But one prominent organization of student activists said the reforms announced Wednesday fell short.

“What students need most is support not criminalization,” said Derrianna Ford, a rising senior and youth leader in the group VOYCE. “In order to truly create a safe environment in all of our schools, we need trauma-informed approaches that support students’ mental health such as social workers, counselors, restorative practices. We cannot expect the same police officers who brutalize us on the streets to be our mental health workers inside our schools.”

The new slate of reforms comes on the same day that Chicago publicly released student arrest data. While the data show an 80% decline in the number of arrests on school campuses from 2012 to 2019, the numbers show that Black students are still disproportionately detained on campuses. Last school year, of the 651 students that the district reported as arrested on campus, 526 of them — or 80%— were identified as Black, 107 were Latino, and 16 were white.

Community leaders and parents have long voiced concerns about the “school-to-prison pipeline,” an issue Jackson addressed directly on Wednesday.

“Rates of arrests among Black students remain unacceptably high, and we must remain focused on addressing this as a school district,” she said. “We will do that.”

Perhaps the most sweeping change: The city will more closely examine misconduct allegations for officers who serve on campuses and raise the bar on the disciplinary record on who can serve. No officers with sustained allegations of excessive force in the past five years will be allowed to serve on campuses, nor will officers who’ve had sustained complaints about verbal or physical alterations with youth.

A Chalkbeat review of school-based officers who served last year showed that 96% faced allegations of misconduct, according to the Citizens Police Data Project, a database of police disciplinary records.

Those allegations range from excessive force, searches without a warrant, and physical domestic altercations to more minor accusations like traffic violations. The alleged violations were sustained — found to be true — for 41% of officers serving in schools this year.

“A lot of feedback we received during (the reform) process was that we need to strengthen our selection criteria. This year we are moving to excellent disciplinary history — we are tightening those parameters,” said Jadine Chou, chief of safety and security for Chicago Public Schools.

As for whether Chicago can implement the latest round of reforms in the next three weeks before school starts, Chou said the all-virtual start to school gives the school district and police department more time for additional training.

Leaders also said they plan to put authority over school police officers under the third in command at the police department. Previously, the system was decentralized, with district commanders largely making decisions about who serves on campuses, oftentimes with little input from schools.

Chicago last year began embarking on the biggest overhaul of its school policing program in a decade as part of broader police reforms. In 2014, the cover up of the fatal shooting of teenager Laquan McDonald provoked widespread outrage and protests, which culminated in a civil rights lawsuit that the city ultimately settled. Schools were included in a resulting federal consent decree.

However, many of the promised reforms had not materialized by the time school campuses shut down in March amid the coronavirus pandemic. Officers did undergo a 40-hour training program, and a formal $33 million contract was signed between the school district and the city’s police department — a contract that will now likely be cut in half, once the school board votes on a new budget proposal next week.

But despite a formal requirement to screen officers, nearly half had misconduct allegations sustained against them. Schools still lacked a system to register complaints. Some principals remained confused about which situations in which police can and can’t get involved. And some students, teachers, and Local School Council members said they knew little to nothing about any overhaul in school policing.

Exactly who had responsibility and oversight over the program and vague details about the officers’ backgrounds and responsibilities still left parents, students, and educators worried.

Then summer brought a significant sea change, with a wave of youth-led activism following the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis at the hands of a white police officer. Scrutiny of school police became a central theme in Chicago. And as the mayor and schools chief pushed the decision-making down to school councils, the local groups took votes. In the end, the majority voted to keep officers, though many community members said the process was flawed and too many councils lacked enough membership to take a formal vote. About 1 in 4 schools voted them out.

Asked about transparency problems and reported violations of the Open Meetings Act that were documented during the votes — a review of multiple meetings by Block Club Chicago and Chalkbeat showed some councils didn’t follow the rules governing public access and participation — Jackson said Wednesday that the district had begun tracking the meetings and votes centrally and was helping ensure councils be more publicly accountable.

Some community organizers say the district’s efforts to build more transparency within councils have not gone far enough and that too much responsibility suddenly was thrust upon the public bodies made up of parents, educators, and community members.

In addition to cutting back the budget for the police program, the city’s school board will vote next week on the proposed reforms, part of a broader revised agreement between the district and the police department.