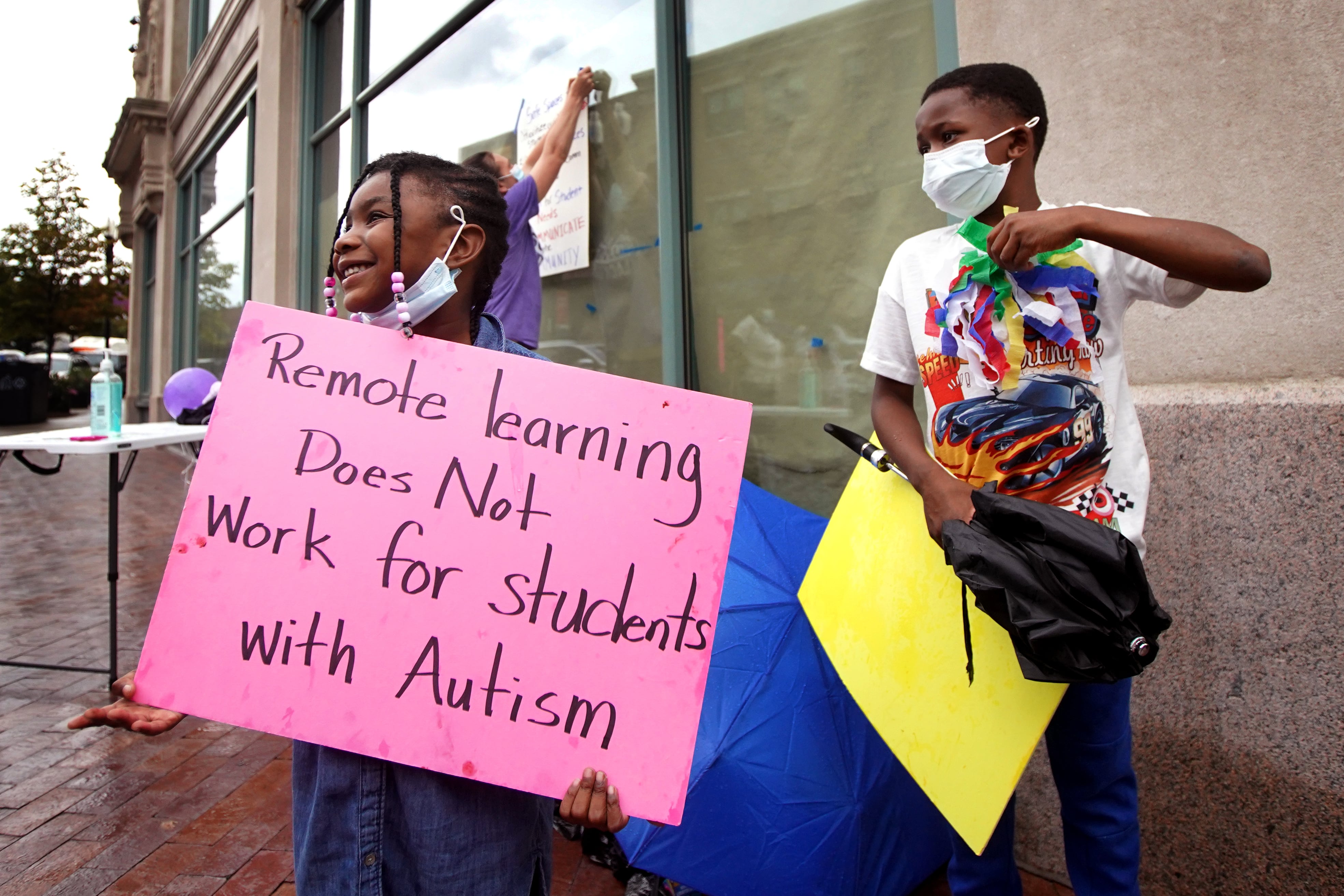

Chicago families started the school year by logging onto online classes last week. All parents are struggling to navigate remote learning, childcare, and work. For parents of children with special needs, those issues are magnified.

When school buildings were open, children with special needs were able to have a special education classroom assistant to help them stay on task in class. Students had critical sessions with a school psychologist, occupational therapist or speech-language pathologist. In the spring, those services vanished for some students for months, and some families didn’t regain them for the rest of the school year.

Chicago Public Schools has pledged this year will be better for students in special education. But it’s still unclear how the district will provide some services virtually — and the burden on parents is huge. Many are already overwhelmed.

Below are the experiences of three Chicago families as they navigated their first week of school.

Chalkbeat is collecting the experiences of special education families through a survey. You also can send us an email at chicago.tips@chalkbeat.org.

One parent worries about going back to work without child care

Mary Ottinot is a mother of three children with special needs. Ottinot’s youngest child —who she asked Chalkbeat not to name — is a kindergartener with autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, and cerebral palsy. She needs the most support with virtual classes, her mother said.

Before the coronavirus closed school buildings in the spring, Ottinot’s daughter had a paraprofessional to help her with class assignments, consultations with a speech-language pathologist weekly to help her understand how language works, and sessions with a social worker. Without a paraprofessional sitting beside her to help her click links or focus on classwork, it’s difficult for her to do her schoolwork.

Ottinot’s daughter has brain damage that affects how she processes language. She can lose her train of thought mid-sentence, and when that happens she needs an adult to intervene and help her.

Ottinot doesn’t know how her daughter is going to receive therapy virtually. “She needs to learn how to speak to her peers. When she has blocks in her conversation, the speech pathologist is supposed to be setting up the environment so that she’s able to participate.”

For Ottinot, it’s not that her daughter struggles to adjust to remote learning, it’s that she needs to be in a classroom.“With the type of support that she needs I don’t know how you do that with the constraints of remote learning. It’s very difficult,” she said.

Another issue that Ottinot faces is childcare. In addition to her 5 year old, she has children aged 12 and 15.

Ottinot is a nurse who cannot work from home and cannot go to work without having someone watch her children. Ottinot applied for her family to receive childcare from the district, which is operating childcare sites at six schools around the city. She said her application was denied.

“I can’t leave my daughter. I don’t even know how I’m going to go to work but I need to go back,” she said.

Even when Ottinot can return, she’s worried about exposing her children to the coronavirus — children with disabilities can have underlying health conditions that make them more susceptible to serious illness. But there aren’t many options for her to work remotely and she has to financially support her family.

The family that looks forward to their child returning back to school

Yolanda Williams’ daughter, Kaylynn, is a 13-year-old with Down syndrome. Kaylynn is an eighth grader at William Penn Elementary School located in North Lawndale on the city’s West Side.

Since school started, Williams has logged in alongside her daughter to help her use online applications and keep her on task with her classwork. Williams and her daughter have come up with a rhythm: Short bursts of schoolwork over 20-minute increments because Kaylynn has a short attention span.

The key to a successful day is setting and maintaining a strict routine, Williams said. “If you come outside of that routine, and not explain to her why, you’ll just discombobulate her and throw her off for the rest of the day. It’s hard for her to break habits.”

One habit that seems to bring a sense of normalcy is Kaylynn’s school uniform. Each morning, the teen puts on her red polo shirt and khaki pants, and at 8 a.m. she signs online to start classes and eat breakfast. Throughout the day, she takes a variety of classes like math, English, and gym. Williams also has a yoga mat for her daughter and makes space in their apartment so that she can do jumping jacks and other exercises.

So far, remote learning has been going well, Williams said, even though the six-hour day feels too long.

Like some families in the city, Williams has been able to support her family while working at home since she works as a tailor doing alterations on suits and dresses. Williams volunteers as an advocate for children in early education, and before the pandemic she used to knock on doors and canvas for different campaigns. She also is the president of Penn’s parent advisory council. Now, she does her volunteer work online.

Being able to shift work, volunteering, and school online has been useful because Kaylynn, Williams and Williams’ 81 year old mother —who lives in the same apartment building — are all vulnerable to the virus.

She hopes that her daughter can go back to school because remote learning is “is kind of hard and it’s boring. She should be changing classes; going to the library and gym. My daughter is restless from being cooped up in a house all day.”

The family worried about what’s next

Chelsea Ferrer struggled with the abrupt closure of schools last spring. The high school senior, who has autism and attends Back of the Yards High School on the city’s Southwest Side, struggled to understand and come to terms with the idea that a virus had shuttered her school and cut her off from her teachers and classmates. Not only was she disconnected from her school’s community, her mother Consuelo Martinez said, but it was hard to transition to online learning.

Teachers and support staff held a virtual meeting with Chelsea and her parents to answer her questions about remote learning and reassure her, with an educator interpreting for her parents — who are Spanish speakers. That helped a lot. Still, said Martinez, “March and April were really hard.” Chelsea wanted to call her teachers with questions about coursework all the time, including late in the evening. Things got easier by the end of the school year.

This school year started more smoothly thanks to extra time to plan and prepare for both teachers and families. Martinez said the extra structure and predictability in the school day is helpful for her daughter, who thrives on routine. She has been able to navigate her virtual classes more independently while her mother works during the day.

There have been rough moments: Mid-week, a tearful Chelsea called her mom at work to tell her the computer wasn’t working any more. “It’s my fault,” she kept saying. “I can’t see my teachers any more.” Martinez left work and drove home, only to discover the internet at her home was down. By the time Martinez was able to resolve the issue with the family’s internet provider, Chelsea had missed three classes — a major blow to her.

Overall, Martinez says the more structured school day with a set daily schedule is helping Chelsea navigate learning more independently. However, the family is struggling with the uncertainty of a school year that started virtually but could involve at least a partial return to school buildings later in the year.

Martinez hopes that the district will alert parents sooner to changes of plans — most notably, when it decides to start bringing students back to campuses. Parents need plenty of time to prepare themselves and their children, she said.

“For students who are diverse learners, those transitions are the most difficult part,” she said.