After intense opposition from the teachers union, Chicago Public Schools opened its buildings to teachers on Monday for the first time since schools closed in March.

A small group of pre-K and special education students are expected to follow next week.

The reopening has amped up tensions between the union and district leaders, and how the first weeks unfold could set the stage for the district’s broader plans to bring back students in kindergarten to eighth grade in February.

Here’s what we know so far.

- Chicago meets the current metric health officials set for school reopening, though some health experts have raised concerns.

The current metric Chicago school officials said they will use to determine if it’s safe to reopen schools is how long it takes the number of confirmed positive COVID-19 cases to double. If it takes more than 18 days for the the case rate to double, it’s a green light. It’s a shift from using a seven-day average positivity rate to assess community spread.

With Chicago’s current doubling time at 90.8 days as of Sunday, the district is on track to reopen, even as health officials expect to see a slight uptick in cases in the days ahead due to holiday celebrations and travel.

The district’s evolving metrics have been the target of some criticism, both from the teachers union, which wants a target 7-day positivity rate of 3%, as well as some public health officials, who say the figure is incomplete.

A fall overview of research from around the world concluded that transmission can occur among school-age children, but there is little evidence that schools have been a driver of transmission.

2. The district has spent millions to prepare schools for a safe reopening, but what that looks like will vary school to school.

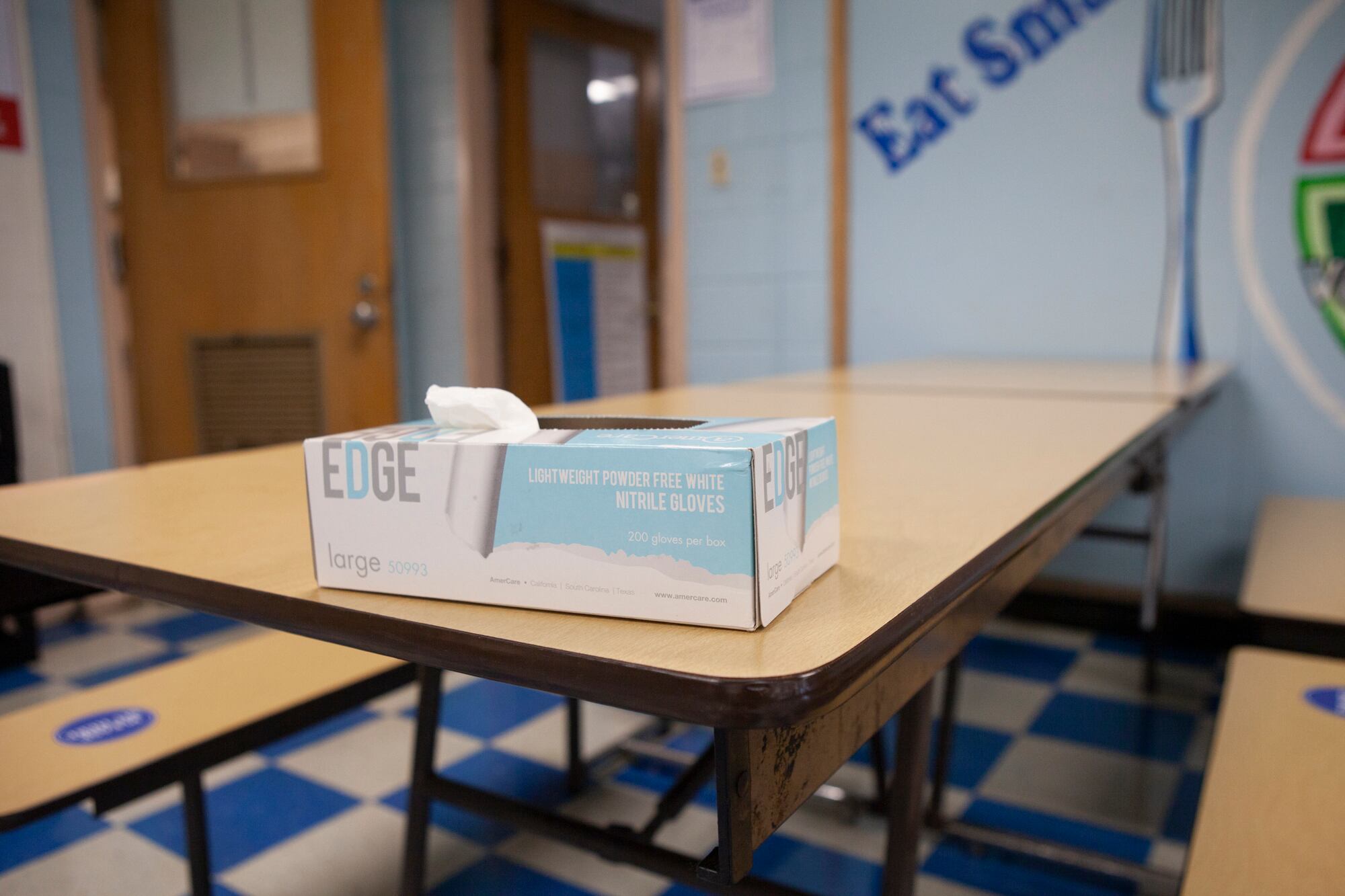

Chicago has more than 500 district-run campuses. Each school will follow some basic safety protocol, including a daily online symptom screener, temperature checks, mask requirements, student pods, and desks spaced six feet apart.

But other details, such as where sick students will wait, how the building will handle staff who see multiple students, or specific cleaning schedules, will be handled at the individual school level.

One historic tension stoked in the reopening plan is school cleanliness. Chicago has previously been criticized for shortcutting efforts to keep schools clean, in part by outsourcing janitorial services that left classrooms battling rodent problems. In recent months, parents and educators have pressed the district to spell out its plans to hire more janitors and deep clean school buildings. At last count, district leaders said they planned to hire 400 additional janitors but have not yet reached that number.

As of December, Chicago Public Schools said it had spent $41 million on masks, signs and air purifiers to prepare schools to reopen. It should soon have more resources at its disposal. The school district expects to receive about $800 million from the coronavirus relief package passed last month, netting an estimated $720 million after it sets aside $80 million for private schools.

While schools chief Janice Jackson said $343 million could be used to close a midyear budget hole, $375 million will go toward emergency expenses connected to remote learning and reopening campuses this school year and next.

3. The district said most teachers planned to return, but some have declined to do so.

District figures released in December showed that 5,883 staff members were expected to return to buildings Monday, about 83% of the more than 7,000 teachers, clinicians and therapists the district called back. Some requests for accommodations from teachers were still processing, according to the data. Thousands more staff will be in line to return Jan. 25 ahead of the February return of K-8 students.

But the city’s teachers union, and some educators themselves, have opposed a return to school, arguing that it is unsafe amid rising COVID-19 rates and immediately after holiday travel.

The union, which has been a vocal opponent of the district’s reopening plan, urged teachers who felt unsafe not to return to buildings Monday. Instead, the union provided teachers with a letter stating their contractual right to a safe working environment to give to principals.

Teachers also held a series of public actions: Some teachers at Brentano Elementary in Logan Square spent Monday morning working outside in a classroom staged amid snow piles and in below-freezing weather. Others worked from their cars, and some teachers went into the building.

For teachers who were called back but choose not to return, the consequences could be severe, including disciplinary action or possible firing.

“It’s in no one’s interest to fire teachers,” Jackson said in an interview with local news channel Fox32 Monday. “But I do want to be clear: We have policies and procedures in place for people who are absent without leave in our school system, and we intend to follow those policies and procedures across the board.”

Months of negotiations between the union and school officials have failed to net an agreement. The union has said that the district isn’t bargaining in good faith and doesn’t send its top leadership to negotiations. The district, meanwhile, said the union was late to bring forward concrete proposals.

The growing intensity of the conflict is reminiscent of last fall, when teachers walked out on an 11-day strike after weeks of stalled negotiations.

4. One in 3 students is expected to return, but parents can still change their minds.

Chicago is doing a gradual return for its students, with pre-K and some special education students first in line to return to buildings on Jan. 11 and elementary students set to come back in February.

Family survey results released by the district last year show that 6,470 students, or 38.2%, opted for in-person learning, out of the 16,944 students eligible to return on Jan. 11.

Numbers vary by school. Some expect most of their students to return, while others expect only a handful. Most schools anticipating the fewest students are in Black and Latino neighborhoods with high rates of COVID-19 infections or deaths, WBEZ reported.

Districtwide, a disproportionate number of white students in elementary school have said they plan to return, raising concerns that some of the Black and Latino families most struggling with remote learning aren’t comfortable returning.

Parents who signed their children up for in-person learning can change their minds at any time. For those who chose to continue remotely, the next chance to sign up for in-person learning will be in the spring.

Meanwhile, several Local School Councils, representative bodies made of parents, teachers and community members, have also passed resolutions against a return to in-person learning in recent weeks. Like the alderman’s letter, those resolutions are symbolic and don’t have the authority to shift school-level reopening plans.

5. Chicago politicians have waded into the debate.

More than half of Chicago’s aldermen signed a letter released Sunday raising concerns with the district’s reopening plan. The letter, signed by 32 of the council’s 50 members, requests the district provide reopening metrics that take into consideration varying COVID-19 levels among different neighborhoods and give updates on the plan to hire 2,000 support staff for reopening.

The letter offers a show of support to educators who have been vocal about their reopening concerns. But in a mayoral-controlled school district, the gesture is largely symbolic and unlikely to push a shift in the district’s plan.

In a nine-page response letter, Jackson said reopening was an issue of equity for Black and Latino families who have been poorly served by remote learning. In a series of bullet points that addressed the aldermanic concerns, Jackson said that health officials now said in-person learning had been proven to be safe at higher COVID-19 positivity rates than previously understood.

Still, the enmity between the mayor and teachers union, which underlay much of the negotiations around the 2019 teachers strike, is likely to affect efforts to reach an agreement on school reopening.

In Washington D.C., a mix of shifting city planning and union demands, along with a lack of trust on both sides, has so far thwarted the district from reopening schools altogether.

6. The governor has said teachers will be in the next phase of vaccinations, but it’s too early to say when.

As healthcare workers in Illinois have begun receiving the first dose of their COVID-19 vaccines, teachers have begun to wonder: Where are we on the list?

In December, in response to questions from Chalkbeat, Gov. J.B. Pritzker said that teachers would be in the next phase of vaccinations after health care workers and staff in long-term care facilities — a phase that Chicago health chief Alison Arwady has called 1b. That could happen as early as February.

Speaking Monday, Arwady said the pace of the vaccination rollout was slower than expected, and it could take 70 to 80 weeks for all Chicago residents to get vaccinated if current distribution patterns hold. But there are many variables that could speed up the timeline. “It’s hard to have a crystal ball for these things,” she said.

One silver lining: Arwady said health experts are hopeful that vaccinations for children will begin in earnest this summer. The first wave of vaccination trials prioritized adults.

Where teachers fall in the vaccination queue so far appears to vary state by state. Educators in Colorado and Tennessee were moved up on the priority list by state officials just before the new year, putting them on track to get the shot in the early months of 2021. Still, in Colorado, the new higher priority level includes more than a million people.

7. Statewide, and nationally, more school districts are moving toward reopening.

Chicago is not the only district moving toward reopening amid controversy. Illinois’ second-largest district, Elgin U-46, plans to reopen school buildings to elementary students next week, with middle and high schoolers set to return Jan. 19. Chicago has not yet set a date to reopen its high schools.

Speaking Monday on WBEZ’s Reset, Elgin Superintendent Tony Sanders described the complexities of reopening campuses and hearing high emotions from parents and educators alike. “Nobody has all the right answers in the current environment,” said Sanders. “This is like a snow day on steroids.” District leadership had been closely working with the teachers union there. Still, “not everyone was happy.”

On the national stage, President-elect Biden has made it clear his goal is to safely open the majority of schools in his first 100 days in office. December reports said the Biden team was weighing a considerable campaign to pay for weekly testing of teachers and students to make that vision a reality.

Cassie Walker Burke contributed reporting.