The debate over whether Chicago should embrace an elected school board has a new twist: A mayor-backed proposal for a hybrid board that would continue to give City Hall influence.

Sen. Kimberly Lightford filed legislation last week with the Senate that would create a hybrid school board. Under the plan, the majority of the board would be appointed by the mayor with a few elected seats.

Meanwhile, a bill that would establish a 21-person elected school board has picked up speed in the Illinois legislature. Currently, the fully elected school board bills are moving fast through the general assembly.

Here’s what you need to know about the current conversation.

The mayor’s proposal would not entirely eliminate mayoral control.

Under the city-backed proposal, the mayor would appoint five members of a seven-member board. Two members would be elected by the public, for a total of seven seats in 2026. (The current board has seven members, all appointed by the mayor.) In 2028, the board would expand to 11 seats. With the expansion, the mayor would still appoint the majority of the board, with eight appointed members and three elected members.

The board could then revert back to a mayoral-controlled seven-member board in 2032.

The legislation says that the mayor must appoint people who reflect the diversity of the city. To be eligible for an elected or an appointed seat, a board member would need to have served on one of the following for at least two of the 10 years preceding the date of the election: a Local School Council, the governing board of a charter school or contract schools, or the board of the governors of a military academy.

All board members would receive an annual salary of $40,000. Currently, school board members across the state are not paid and can’t have any financial interests in the district that they serve.

The hybrid proposal has come late in the game.

Proponents of the elected school board push have been organizing around the proposal that would establish a 21-person elected board for years, but the reopening debate appears to have helped recruit supporters. The legislation cleared another hurdle in the Illinois House last week, passing through committee with 71 votes in support, 39 against and 3 abstaining.

The Senate executive committee also voted last week to pass the Senate version of the bill, sponsored by Sen. Robert Martwick, with an 11 to 5 vote. It will head for a second reading on April 20 before further action is taken.

Supporters of the elected school board don’t have a clear path to victory.

Proponents of having a fully elected school board have been here before. In 2019, a bill to create an elected school board passed in the House, but was not called to the Senate floor. This happened again during the lame-duck session in January.

The issue might not be resolved this session either, despite support from members of the general assembly, community organizers, and parent advocacy groups.

Both proposals have critics.

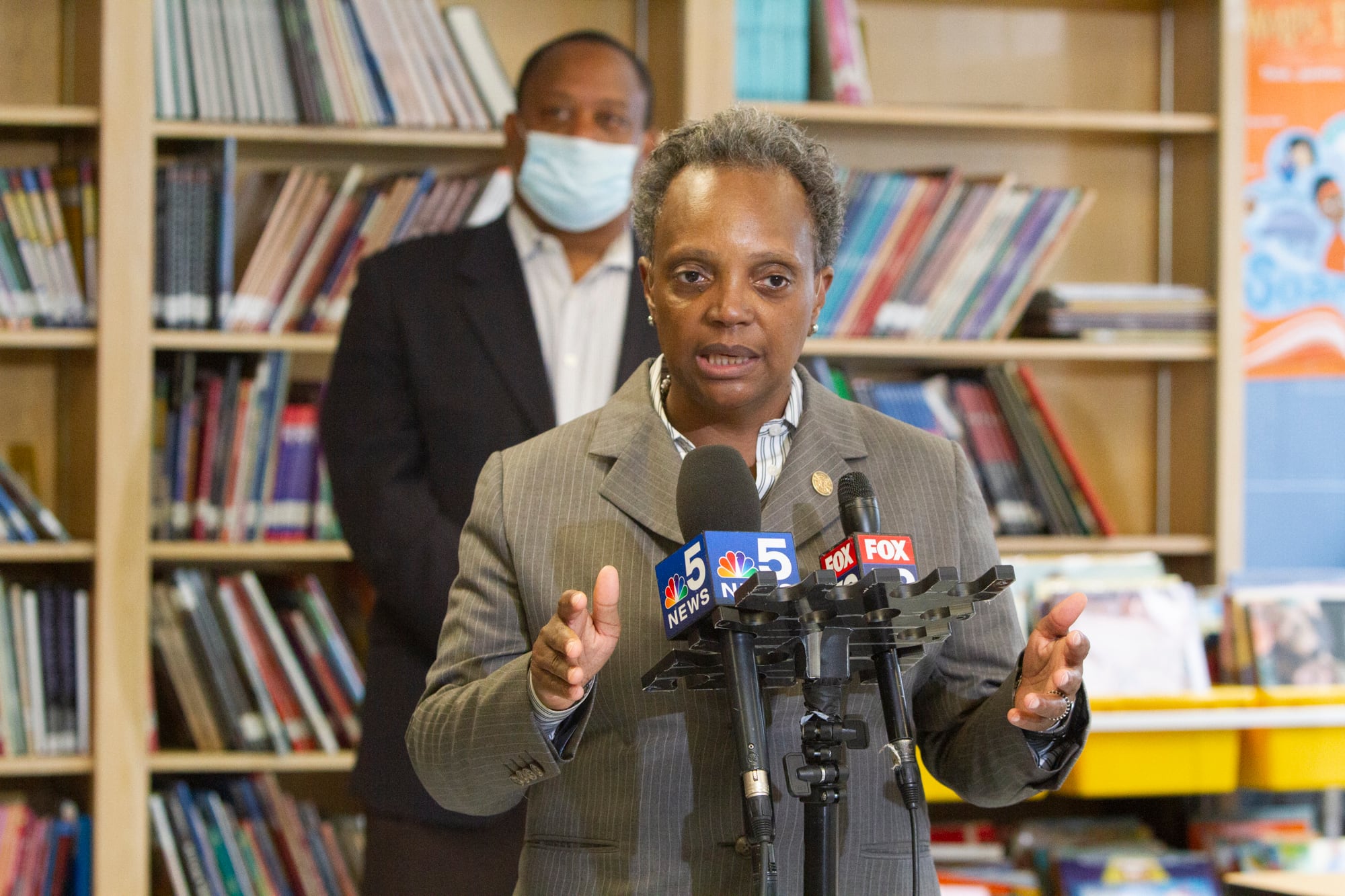

Proponents of the fully elected school board bill want to ensure that members of the board are held accountable by the public through regular elections. A hybrid school board, under the current proposal backed by Mayor Lori Lightfoot, would ensure that the majority of the board remained political appointees.

Jitu Brown, board president of the Kenwood-Oakland Community Organization, talked about the decades-long battle for an elected school board during the Senate Executive Committee hearing last week. Brown said the call for an elected school board was a direct response to past decisions by the appointed school board to close down multiple schools on the city’s South and West sides, which disproportionately affected Black and Latino low-income families.

“[Chicagoans] want an elected representative school board. I want to be clear: not a hybrid. Not mayoral-control light. The one thing we understood with this school board, who could raise our taxes, was that there is no instrument to hold them accountable,” he said.

However, critics of the fully elected school board bill worry that an elected board would not represent the city’s diverse population. In a letter published in Politico, a group of advocates said they want to make sure that parents who are undocumented or are low income are represented on an elected board. The current bill does not allow parents who are undocumented to serve on the board.

“These parents entrust their children and their children’s future to CPS. They deserve a voice — and a vote —in any new governance structure,” they wrote.

The advocates expressed concern about the cost of elections, citing the steep costs of school board elections in Los Angeles. The group also is concerned about balancing members with parental experiences and those with expertise in education. They want parents to be the primary voice of the board, but include members with expertise in administrative work in education.