Leslie Trejo, like most parents, doesn’t like playing the bad guy. But this school year, she has accepted the role, if it gets her kindergarten daughter the extra reading practice she needs.

At Trejo’s home in Little Village, that means taking 15 minutes on Saturday afternoon to practice memorizing words such as “of,” “to,” and “was” — all while asking her third grade daughter to play nearby. The lesson: fun comes after flashcards.

Ann Miller, a parent in Lakeview, has had a similar struggle. She wanted to gauge her daughter’s reading ability, but the independent-minded child refused to read to her mother. So Miller convinced her daughter to read to the cat — and eavesdropped.

“The biggest frustration I had was I couldn’t really tell if she was doing well or not,” said Miller.

When COVID-19 forced schooling into the home, Chicago families found themselves suddenly on the front lines: watching, coaxing, teaching, and sometimes, throwing up their hands in frustration as their children tried to learn the basic building blocks of reading.

The already difficult — and crucial — process of learning to read was made even more complicated this year by disparities in remote learning experiences coupled with wide-ranging inconsistency in how Chicago schools teach reading. That has raised big questions about whether children learned critical early reading skills this year — and what should be done to help struggling readers catch up.

More than a year into remote schooling, no one seems to know how many Chicago children learned to read in the pandemic and how many have fallen behind.

Uneven approaches and inequitable environments

When Illinois closed down schools in March 2020 to avoid the spread of the coronavirus, educators across the city were thrust into a new teaching environment, forced to create a remote learning plan almost from scratch and without a roadmap.

The stakes were particularly high for early learners just beginning to read. Adults who are confident readers, likely in part because they had strong instruction in early grades, are better able to advocate for themselves at work, navigate health guidance or work higher paying jobs.

But most common reading curriculums assumed one key factor: that children are taught in person.

To address some of those gaps in reading and other subjects under remote learning, the district suggested curricular areas that teachers should prioritize, held training on teaching remotely, and told families about the district’s virtual library book system.

To assess students, the district pointed teachers to an online tool called Amplify Reading literacy, which relies on teachers listening to students read. They also introduced a district-run assessment system that allows teachers to create their own tests.

But those efforts ran up against a decentralized reading education system rooted in an approach that experts criticize and the vastly varied learning environments of students during the pandemic.

Under the district’s decentralized reading plan, schools choose the reading curriculums they use from a district-approved list. One benefit of that approach is that teachers can lean on a wide array of curricula and arguably better tailor lessons for specific student groups, such as dual-language learners.

“The biggest frustration I had was I couldn’t really tell if she was doing well or not.”

But there are downsides, too. Many of the district’s preferred curriculums are rooted in the balanced literacy model, which uses a mix of individual and group reading, context clues, some phonics, and writing practice to teach reading. Critics say that approach isn’t supported by the science of how children learn basic reading skills.

The combination of the preferred curriculums and decentralized oversight means the district may not know how reading is taught in every classroom and could leave instructional gaps. Last spring, the district identified about 55 elementary schools that didn’t have a phonics program sufficient for early literacy development.

Then there are the challenges of remote learning. Even with the same instruction, one student could be learning from a daycare center with a literacy expert, another at home with a parent nearby but a spotty internet connection, and a third surrounded by siblings.

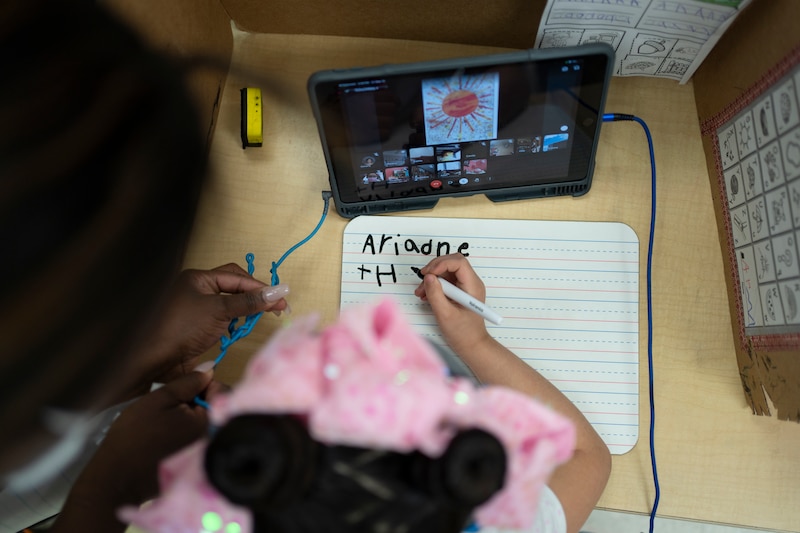

“The environment is the thing that is not equitable,” says Mount Vernon Elementary School kindergarten teacher L’Rae Robinson.

Chicago school officials say they share the concern about how the past year impacted the city’s young learners. “We know that the pandemic has had a negative impact on the consistency of access to effective instruction for many students,” said spokesperson James Gherardi in a statement. “And that impact has been most pronounced for our nation’s youngest learners.”

Teachers say they are split on how much to rely on test scores to paint a districtwide picture of literacy during the pandemic. They can’t say, according to some of the usual measures like test scores, how a year of teaching amid uncertainty, amid stress, and through a new medium have gone for children. But, they also wonder, are test scores the right tool?

For first-grade teacher DeJernet Farder, acknowledging the difficulty of the pandemic year especially on young students who may have trouble articulating all of their feelings or understanding the stresses around them, is essential. But she doesn’t look at the past year through the frame of losses or gains.

“The kids are not going to come in at grade level,” Farder, who teaches first grade at Morton School of Excellence in Garfield Park, said. Instead, she has made sure her students have touched on the major learning points of first grade, even if they didn’t go deeply into past tense or identifying verbs, so that they have some grounding.

Quite simply, Farder says, kids shouldn’t be punished for not learning what they haven’t been taught.

Embracing ‘chaos’

As teachers are assessing students, anxious parents are doing the same, but often without tools, support or, at times, their children’s cooperation.

“Our parents have basically become student teachers,” said first-grade teacher L’Rae Robinson. “Their kids may be learning to read, but they are also learning to teach.”

Families have tried to learn teaching skills like sounding out words. They triage concerns between their child’s classroom teacher and daycare supervisor. Sometimes, they just make sure their child feels confident in the process.

It has been a team project for Leslie Trejo, who works as a medical assistant at Rush Hospital, to follow her daughter’s progress in reading. The first line of information is her classroom teacher, who shares lessons and leads small groups; then comes Candice Washington, an early childhood educator at the daycare center where Trejo’s daughter learns online every day with 15 other remote kindergarten learners from schools all over the city. Finally, there is Trejo herself, who fills in the gaps on weekends and evenings.

Trejo has learned about “sight words,” which are connective words like “to,” “my” and “was” that readers are expected to memorize, and also how to communicate with teachers through an app called ClassDojo. She’s also learned, in many ways, what learning looks like.

Michelle Bautista has learned to have realistic expectations for her bilingual son so that he doesn’t internalize her anxiety about the reading process.

“When the teacher said he might be behind in first grade, she was trying to do her best to inform me that he needs more practice and is not getting it,” said Bautista, who works full-time from home and switches off checking in on her son in 15-minute increments with her husband. “It’s such a delicate balance, I want him to love reading. I don’t want him to look at this as a pressure-filled task.”

So, says Bautista, “I have embraced the chaos.”

Confidence was the key for Shauna Schumer’s first-grade daughter, who would get frustrated or embarrassed and close the computer if she was struggling to read a word. “Anything with reading or writing was an automatic meltdown because she didn’t have the confidence,” Schumer said. “She knew she was behind, and it was hard for the teacher to not be right there to comfort her.”

“Our parents have basically become student teachers. Their kids may be learning to read, but they are also learning to teach.”

Still, taking cues from her daughter’s own assessment of how school was going wasn’t always accurate, Schumer found. “At one point, I was thinking she was further behind than she was,” she said. “And then I talked to the teacher, and I was like, oh, I didn’t realize she could do that!”

That’s been the key takeaway of this time for Nell Duke, a professor at the University of Michigan School of Education. “There are two important insights from this year that I hope will stay with us moving forward: the ways in which social emotional experiences are intertwined with reading,” said Duke. “And I’m hoping this experience helps to forge stronger partnerships between families and schools around literacy development.”

Changes on the horizon

District officials acknowledge the disparate impacts of the pandemic year on young learners and have said they have offered specific support to primary grade teachers.

“CPS has doubled-down on support to primary grades teachers through the CPS Early Literacy Collaborative to ensure a strong focus on foundational skills instruction balanced with the abundant reading of diverse and engaging texts,” said district spokesperson Gherardi.

Officials say other critical changes are on the horizon, including a forthcoming plan that would spell out ways schools can address missed learning. But they haven’t yet offered many details.

Leaders also have touted the summer debut of a new curriculum initiative called Skyline, part of a $135 million promise to create high-quality instructional material that would be available for all educators. The city piloted the effort at 38 schools. The district hasn’t yet said much about it publicly except that it has phonics components, is more culturally relevant than off-the-shelf programs, and has strong bilingual reading options.

It will be optional for schools to adopt, and Chicago will still lean on recommended curriculum lists and not required ones, so schools will still have a lot of leeway in how they teach reading.

Meanwhile, some education experts have argued that the district needs to reevaluate its entire approach.

They say that, without prioritizing phonics, reading out loud or memorizing words won’t be a fully effective learning strategy. “Online learning is likely just to exacerbate the problems you see in a balanced literacy classroom where kids are just falling further and further behind because they are not getting enough practice in a variety of patterns“ of reading instruction, Barbara Foorman, a reading expert at Florida State University, told Chalkbeat at the start of the pandemic.

The district has also come under fire from both parents and teachers who say it needs to bulk up special education supports and identify reading-based learning disabilities sooner to make sure young learners receive extra support more quickly.

For now, teachers, and schools, are coming up with their own approaches. This spring, L’Rae Robinson’s school administered the NWEA test to in-person students. What teachers there learned was instructive: Students performed well on spelling words and demonstrated strong picture vocabulary, but did poorly in writing.

That wasn’t surprising to Robinson. Months of learning through Google Slides had strengthened some skills and not others. “Writing is essentially the application (of those skills),” she said, “and I’m not able to give them the time and handholding they need.”

For parents, how the district adapts in the coming weeks and months will be something they watch closely. For now, they are clutching even small victories and those moments of progress that bring a wave of pride and relief.

“The first time (my daughter) got every single sight word right, I literally had to walk out of the room because I was starting to cry,” said Schumer. “It was such a struggle.”