Trevor Reed didn’t choose to enroll in the new military science class at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. College Prep on Chicago’s South Side. But he ended up there anyway.

So did hundreds of other Chicago students from King and at least nine other predominantly Black and Latino high schools who are automatically enrolled each year in JROTC, a class designed in part to recruit students for the military, data and interviews show. That practice is now under investigation by the school district’s inspector general.

Last fall, for example, all 110 students in King’s freshman class were placed in JROTC, which stands for Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps — whether they wanted to be there or not.

Data obtained from the district show a clear pattern: automatic enrollment occurring at smaller high schools on the city’s South and West Sides that serve a mostly low-income student body. The city’s larger North Side high schools, where more students are white, have significantly lower percentages of freshmen enrolled in the program.

Debate over the benefits and risks of JROTC programs isn’t new, but the practice of automatically enrolling students in some Chicago schools has invited fresh scrutiny of the program, with some parents and educators calling for changes to the way students are enrolled.

The pushback comes amid a national racial reckoning that has shined a light on how Black communities are policed and viewed, and how students of color are treated. CPS has pledged to address racial disparities in access to career and college readiness programs that are lacking at under-funded schools, where JROTC programs often fill the void.

Within CPS, 94% of JROTC students are Black or Hispanic, while those students account for 83% of total enrollment, according to CPS data. Nationally, more than half of the approximately 550,000 students in JROTC are students of color.

“He never signed up for the program,” said Tineeka Reed, Trevor Reed’s mother. “Fostering kids into classes that they don’t want to take is concerning to me. Schools are supposed to be student-centered. Why aren’t we listening to the students?”

Default enrollment at some schools, not others

The practice of automatically enrolling students in JROTC has been raised multiple times with district leaders, who have yet to stop the practice, according to copies of district emails and interviews with students, teachers, parents and Local School Council members.

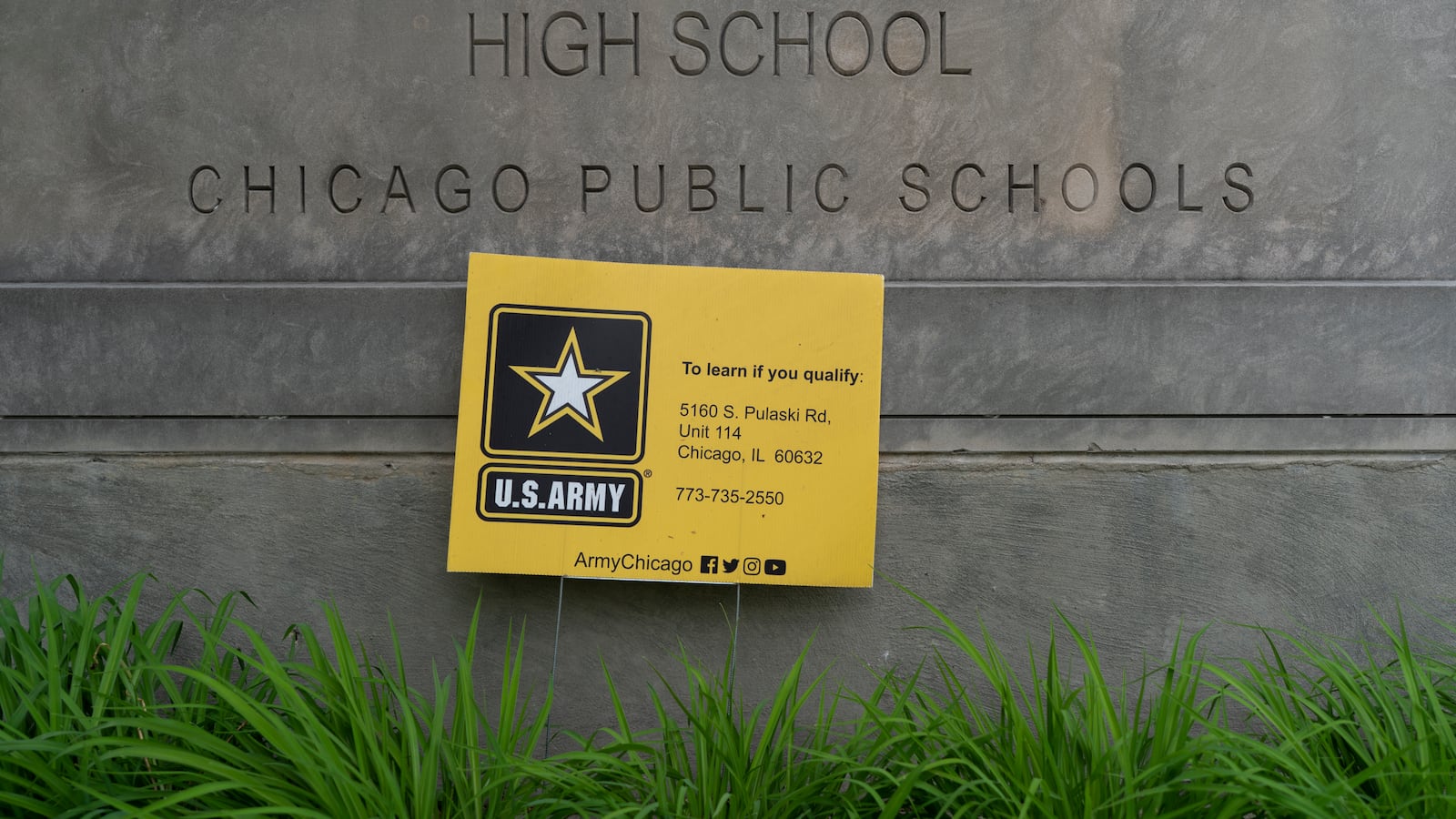

JROTC is a daily class on military science, leadership development and citizenship that seeks to “create favorable attitudes and impressions” toward the armed services and military careers, in part by hosting military recruiters for regular visits. The program is popular among students and promoted as a means to instill confidence and teach valuable leadership skills. But it also has been widely criticized for concentrating in under-resourced schools with sizable Black and Latino enrollment and steering teens toward military careers and away from other educational or job opportunities.

CPS spokesperson James Gherardi said in an email that the program is “voluntary,” but acknowledged that default enrollment occurred at some schools.

“JROTC is a voluntary CPS program open to students at many high schools across the district,” he said. “The district is aware that some schools have enrolled students in JROTC as a default course and those students have the ability to opt out if they do not wish to participate in the program.”

In an interview, retired Col. Daniel L. Baggio, head of CPS’ Department of JROTC Leadership, said JROTC enrollment procedures are decided by individual schools. Parents are asked to sign a statement giving their students permission to participate.

“Parents are informed at the very beginning,” Baggio said. But he noted, “I’m not in every classroom.”

However, Reed, the parent at King, said she did not receive a permission form for her son, who was 17 when he started the JROTC class.

After Chalkbeat asked about automatic JROTC enrollment in April, CPS’ Office of Inspector General opened an investigation into the practice.

“The OIG has initiated a review of JROTC enrollment procedures to ensure CPS’s compliance with all applicable authorities and that students and families have ready access to information about their options,” Inspector General Will Fletcher said in a statement.

Practice prevalent at small high schools

Even though enrollment has declined some in recent years, CPS still claims to have the country’s largest JROTC program, with more than 7,800 students enrolled this year at 44 schools, making it a point of pride for the district and Mayor Lori Lightfoot. Most programs are affiliated with the Army, though a handful of schools have a Navy, Air Force, or Marine program.

Chicago students are far more likely to be enrolled in JROTC — voluntarily or otherwise — than those elsewhere in Illinois: CPS students account for about three out of every five JROTC participants in the state, according to Illinois State Board of Education data.

JROTC enrollment data provided by CPS shows that all or large numbers of freshmen are enrolled in the program at seven small and predominantly Black high schools on the city’s South and West sides — Bowen, Fenger, Harlan, Julian, King, Manley, and Michele Clark — along with Kelvyn Park, Gage Park, and Spry Community Links, three schools where the majority of students are Latino.

Most of the schools have other factors in common: graduation rates below district average and patterns of declining enrollment. Because the schools tend to have fewer students, they are unable to offer as many elective and extracurricular programs as larger schools. That leaves JROTC, which is subsidized by the military, as a compelling option — and, in some cases, as a replacement for traditional classes such as physical education.

Natasha Erskine, a former CPS JROTC participant and U.S. Air Force veteran turned anti-war activist, said the concentration of JROTC programs in predominantly Black and Latino schools raises similar concerns as the over-policing of students of color, an issue that has come under renewed scrutiny over the past year.

After some CPS schools voted last summer to remove police officers from campus, schools are now exploring alternatives to police in their buildings as part of a districtwide review of school safety plans. There has been no formal effort to eliminate or curtail JROTC.

In fact, some school leaders, like the principal at King College Prep, are embracing the program.

The debate at one campus

At King, after the Chicago Board of Education voted last June to approve a new Army JROTC program, all freshmen at the South Side high school were automatically enrolled, according to King teachers and LSC members. More than 95% of King students are Black.

“They didn’t select the program,” said a King teacher who requested anonymity for fear of retribution. “They were involuntarily dropped into the program.”

King Principal Brian Kelly said about 100 freshmen out of a 110-person class remain enrolled in JROTC, which until recently was taught fully online because of the COVID-19 pandemic. He said students who don’t want to participate can be removed from the class, and recalled that 8 to 10 did opt out.

But, the King teacher said, “A lot of parents didn’t know they could do that.”

Baggio, the head of JROTC at CPS, said his department does not track the number of students who opt out of the program. Principals from the other nine schools where all or large numbers of freshmen are enrolled in JROTC either referred questions to CPS spokespeople or did not respond to emails or phone messages.

Kelly, an advocate for the program, said it can help students develop organizational skills and responsibility. He said the program would also help King attract students after years of declining enrollment.

“It’s about me providing different opportunities for students to prepare them for postsecondary success,” the principal said.

JROTC programs also can be attractive to school leaders in part because instructors’ salaries are subsidized by military branches. Because JROTC classes count as physical education credits, principals can cut one or multiple PE teacher positions and use the money saved elsewhere. Students not enrolled in PE are then placed in JROTC or in other alternative classes, if schools have them.

King had three full-time physical education teachers last year. This year, it has just one, according to CPS data and interviews.

Wiley Johnson, a King parent and chair of its Local School Council, which are elected governance groups that weigh in on spending and principal selection, said schools shouldn’t have to rely on JROTC programs to help balance their budgets.

“If you’re 18 years old and you want to join the military because you want to fight for your country or because you believe in the added benefits that come from being a veteran, I support that,” Johnson said. “However, when we have 13-, 14-year-old kids being placed in JROTC classes and then they’re being groomed until they’re 17 or 18 for a life in the military, to me, I think that’s really unfortunate.”

Before approving King’s JROTC program, Johnson said the district denied the school’s application for a STEM Early College program that would have focused on science, technology, and math.

“You’re saying that my kid isn’t good enough to have an enriching [Early College] program coming to the school that could benefit them in the short-term and long-term, but pushing them toward the military is fine,” Johnson said. “That really bothered me as a parent.”

King’s principal said he was not worried about his students being recruited to enlist in armed services.

“I don’t see that as a concern,” Kelly said. “I’m not trying to get more people to join the military. I’m trying to prepare them for civic life.”

The push for expansion nationwide

Automatic or involuntary JROTC enrollment is not unique to Chicago, though it’s unclear how widespread the practice is.

A spokesperson for the U.S. Army Cadet Command, which oversees the Army’s JROTC operation, said that the department does not set enrollment policy for school districts, and that JROTC programs are solely managed by their host schools and districts.

School districts in Buffalo, N.Y., and San Diego came under fire for automatically enrolling students in JROTC in 2005 and 2008, respectively. The Buffalo district had been violating a provision of New York’s state education law that requires written parental consent. Illinois does not appear to have such a requirement.

Seth Kershner, a researcher at the University of Massachusetts Amherst who studies the military’s role in public education, said high school students and others organized to overturn compulsory JROTC enrollment in the 1960s and ‘70s in cities like Atlanta, Memphis, New York, and St. Louis.

More recently, schools that mandate participation in JROTC have been less overt about the practice, Kershner said.

Currently, there are efforts to boost JROTC enrollment nationwide. A bill introduced in the U.S. Senate last year aims to nearly double the number of JROTC programs, from about 3,400 currently to no less than 6,000. Two legislators who back the effort, U.S. Reps. Mike Gallagher, R-Wisc., and Mikie Sherrill, D-N.J., said in an op-ed last year that doing so would “expand opportunities for more Americans to serve their country,” especially in “disadvantaged rural and urban communities, where young people long for purpose-driven futures.”

Nationally, research shows that 40% of students who participate in JROTC for three years enroll in a service academy, matriculate into a college ROTC program, or enlist in the armed services. The Army found that students at high schools with JROTC programs are more than twice as likely to enlist after graduation.

The Army cites data showing that JROTC students nationwide outperform their peers in rates reflecting attendance, graduation, and grade-point average, and that they are less likely to exhibit “indiscipline.”

“We do a lot of good for these children in Chicago,” said Baggio, the retired Army colonel who leads CPS’ JROTC department, citing data showing that JROTC students completed 302,000 hours of community service during the 2018-19 school year. “We consider ourselves a beacon of light. We keep cadets off the street. They’re doing wholesome after-school activities. We’ve introduced robotics, STEM-related things. These are skills that take them through life.”

That view of the program raises red flags for critics such as Erskine, who says the forced enrollment practice carries the assumption that Black and Latino students “need disciplining of the military.”

Said Erskine: “That’s also problematic.”

Popular among students

Research is mixed on whether and to what degree participation in JROTC is linked to improved student outcomes. But despite complaints about the way some students are enrolled, JROTC has been popular among many Chicago students.

Brianna Gordon, a former JROTC student who said she chose to enroll in the program at Chicago Vocational High School in Avalon Park, said it was an easy class that involved exercise challenges, drill team competitions, and wearing military-issued uniforms once a week. The class also featured discussions about self-care, such as dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental and behavioral issues.

Through JROTC, Gordon also marched in parades, attended banquets, and helped package toiletries and food for those experiencing homelessness.

“I had a very, very bad attitude, and with them being very understanding and very strict, I learned how to control my attitude a lot,” said Gordon, who graduated in 2018.

Gordon’s former classmate, Nakaya Timberlake, also liked the program, which mimics a military hierarchy. Students start as a “cadet private” and can advance up to the highest rank, “cadet lieutenant colonel.”

Timberlake recalled that when she was promoted to a higher rank, it made her “feel like on top of the world,” she said.

Amir Newell, a King freshman, said he was initially upset when he was automatically enrolled in JROTC. He had been looking forward to selecting his own classes.

But the class turned out OK, he said. In recent weeks, students have studied personal finance, communications lessons, goal-setting activities, and even archery.

Still, Newell said, “I would rather do PE.”