As the promise of spring hung over Chicago, three teenage boys tussled with insomnia, sifting through the fallout of a pandemic year’s interlocking crises.

In Little Village on the West Side, senior Leonel Gonzalez often couldn’t sleep, beset by stubborn what ifs. What if next fall, one of the panic attacks that dogged him during the COVID era creeps up on him on a college campus? What if he didn’t pick the right school? What if he didn’t graduate and go to college at all?

Several miles away one morning before dawn, Derrick Magee and his stepsister, Anna, griped about virtual high school, which Derrick had tuned out weeks ago. Anna pleaded with him not to give up on a trying junior year at Austin College & Career Academy — and with it, on his entire high school career.

And farther north in the Belmont Cragin neighborhood, Nathaniel Martinez would stare at the ceiling and make plans. The sophomore had joined a new push to remove cops from city schools, at a time Chicago was reeling from the police killing of 13-year-old Adam Toledo. But school had receded in Nathaniel’s mind, leaving his grade report card in shambles.

In Chicago and across the country, there is growing evidence that this year has hit Black and Latino boys — young men like Derrick, Nathaniel and Leonel — harder than other students. Amid rising gun violence, a national reckoning over race, bitter school reopening battles and a deadly virus that took the heaviest toll on Black and Latino communities, the year has tested not only these teens, but also the school systems that have historically failed many of them.

It has severed precarious ties to school, derailed college plans and pried gaping academic disparities even wider.

But in this moment of upheaval, educators and advocates also see a chance to rethink how schools serve boys of color. With billions in federal stimulus funds on the way, the crisis is fueling a patchwork of efforts to bring diversity to the teaching cadre, support college-bound teens and more, though a bolder, wholesale overhaul is yet to emerge.

The stakes are high. Even before pandemic disruption set in, boys of color were most likely to drop out, skip college, and end up unemployed.

“This is a critical moment of opportunity to help young men of color,” said Adrian Huerta, a faculty member in the Pullias Center for Higher Education at the University of Southern California, who studies the educational experiences of boys and young men of color. “It’s a national issue, and it will take a national investment.”

Against this backdrop, Leonel tried to become the first in his family to go to college despite sometimes debilitating anxiety. Nathaniel tried to strike a balance between the demands of school, the draw of advocacy, and the escape of video games. Derrick tried to stay in school.

By spring, they faced decisive moments, in the making since the school year’s early weeks.

FALL: Chicago struggles to recreate the school day online

On a sunny Wednesday in October, Leonel, 17, sat in a classroom at Solorio Academy High School, eerily hushed on his first day back since the previous March. In a hoodie and ripped jeans, his hair tied in a ponytail, he had returned to take the SAT, the college entrance test, with other seniors.

But Leonel could not focus.

The hand sanitizer bottles, the masking signage, the one-way traffic stickers — it all unsettled him. He started every time the proctor coughed, exchanging alarmed glances with several girlfriends. They were marooned at socially distanced desks, but having his friends nearby after months of isolation gave him comfort.

He read a passage about astronauts in the English section, but its meaning crumbled.

Even before its COVID-19 makeover, Solorio — a highly rated district school in the Gage Park neighborhood on the Southwest Side, where Leonel lived before his parents split up — hadn’t always felt inviting. In his freshman year, Leonel was bullied in a locker room, and, worried his family would hear about the incident, came out as gay to his parents in a Mother’s Day card. Even as a junior, he walked to school some days, paused in front of the building — and headed back to his house.

Now, at home full-time, his attendance was near-perfect and his grades were up.

But not everything was going so smoothly.

Leonel was in a program called OneGoal, the Cadillac of college application support groups, giving him daily access to a seasoned mentor. But the pandemic had confined their interaction to Google Meet, putting two screens between Leonel and his adviser, Chris Vienna.

Sometimes Vienna felt he was not getting through to Leonel. One minute, the teen rushed to apply to a $32,000-a-year college in Iowa that sent him a marketing email. The next, he seemed paralyzed, making little headway for weeks.

Leonel’s GPA was lackluster, but Vienna pointed to his extracurriculars, such as his service on a string of Solorio committees, where Leonel was usually the only male student: “This is where you look like a badass.”

Leonel, who wants to be a social studies teacher looking out for kids who don’t fit in, yearned to head out of town for college. But he knew his family wanted him to stick around.

That morning at Solorio, Leonel reassured himself the colleges he eyed had made SAT scores optional amid the pandemic. Still, a decent score could boost his spotty high school record.

He tried rereading the astronaut passage. The words jumbled. Finally, he filled out the bubbles next to a string of remaining questions. One random C after another.

Before the pandemic, male Black and Latino students such as Derrick, Nathaniel, and Leonel were key, if complicated, players in Chicago’s storyline of academic resurgence.

District leaders feted them for driving some of the steady growth in test scores and graduation rates that helped erase a one-time label of the nation’s worst school district. A 2017 Stanford University study showed students here grew in reading and math faster than 96% of districts, outpacing wealthier suburban locales. Leaders have credited efforts to cultivate stronger principals, an unflinching look at data, and an ecosystem of nonprofits dedicated to supporting boys of color.

But the five-year graduation rate for Black male students, at roughly 71%, remains almost 15 percentage points behind that for Black females. Latino boys, who have gained on other student groups faster in recent years, still lag almost 10 percentage points behind Latinas. Such gender gaps are the norm nationally as well, the product of a complex tangle of factors, from pressure on young men to contribute financially to disparate school discipline to a shortage of male role models.

On the cusp of the pandemic, Chicago leaders decried signs of backsliding for Black students, such as a dip in SAT scores.

Then came the COVID-19 outbreak — with its disproportionate death toll and economic devastation in America’s Black and brown communities, including the neighborhoods the three Chicago boys call home. By November, the virus had killed more than 3,000 Chicagoans. Black residents, who make up less than 30% of the city’s population, accounted for 40% of COVID deaths.

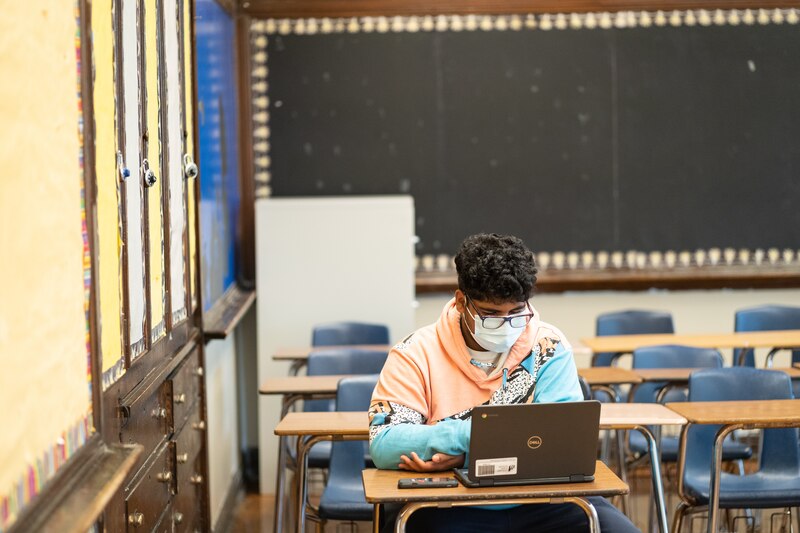

In Austin, on Chicago’s West Side, Derrick, 18, stared at his school-issued laptop. It was late October. Another school day afternoon cooped up in his bedroom. Another blur of impassive rectangles representing classmates who had turned off their cameras in Google Meet, no one but the teachers saying anything for hours. Another gauntlet of virtual classes and educational videos.

It was the same thing over and over again — Derrick’s mantra. A waste of time when he could be doing something to chip in for the family budget. Except today, Derrick would try something different: He would set up an Instagram account for his new business — using stencils to personalize sneakers, at $80 a pop.

Staff at Derrick’s high school, Austin College & Career Academy, where almost all students are Black and poor in one of the neighborhoods hit hard by both the coronavirus and a rise in gun violence, were on social media as well. They tweeted at students with upbeat hashtags: #MondayMotivation or #WellnessWednesday. “Email your teachers to create action plans for getting on track,” they implored. “You and your education matter.”

But Derrick did not follow his school on Twitter. His connection to Austin Academy was shaky even before the pandemic abruptly shuttered the building last spring. At that point, he had decided to sit out the remainder of the year. He thought all his teachers would pass him amid a pandemic. He thought he could return to a reopened school building in September.

He was wrong.

Over the summer, district officials had made a plan to return to in-person learning. But amid teachers union pushback, an uptick in COVID cases, and skepticism from Black and Latino families, they scrapped it. Instead, they set out to rebuild online the brick-and-mortar school day, with its seven classes and scrupulous attendance-taking.

In the fall, short on credits and motivation, Derrick returned to a virtual school that seemed designed to torment guys with ADHD like him. He tried playing monotonous instrumental beats on his laptop as a soundtrack to his classes to settle his mind. But staring at a screen for hours only made him want to pace his apartment. Being isolated just hardened a long-held conviction: Whatever Derrick’s school might tweet, his education didn’t matter to anyone.

Mikala Barrett, an organizer with the student leadership group VOYCE, told Derrick that showing vulnerability was a sign of strength. But Derrick never thought to ask his teachers for help. Not even after his grandma died that fall. Nah, they would not be swayed.

It was the same thing over and over.

He should probably just chuck school until summer and make up his classes then. He pictured himself as a self-reliant entrepreneur, his shoe business taking off.

Nathaniel, the Belmont Cragin sophomore, imagined himself as a student leader, triumphing over a shortage of confidence. On Election Day, the 16-year-old waited in front of a laptop in a church basement in Albany Park, his legs jiggling to the muzak pouring out of the speaker. He sipped nervously from his Dunkin’ Donuts coffee cup while the system autodialed registered voters. At any time, someone might pick up, and Nathaniel would have seconds to nudge him to the polls.

Like Derrick, Nathaniel was involved with VOYCE, and the group had gathered teens for a get-out-the-vote push in Albany Park, on the city’s Northwest Side, where Nathaniel and his mom used to live. In the group, he had found a sense of belonging as he sorted through the complexities of his adolescent identity: Black and Latino, shy gamer and aspiring activist.

This year, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, VOYCE pushed the school district to remove police officers from its campuses. To Nathaniel, the issue felt personal — and complicated.

In 2020, when 774 people were killed in Chicago amid a major violence surge, shootings doubled in Albany Park, pitting its alderman — an advocate for defunding the police — against residents who wanted more neighborhood cops. Nathaniel embraced the goal of replacing school cops with counselors, but after his school’s governing council voted to remove the officers, he also worried about gang tensions seeping in.

Nathaniel went to the neighborhood Roosevelt High School, but his heart wasn’t in it that fall. There was the impulse to get involved through advocacy. Then, there was the pull of video games, which took up more and more of his time. With his school’s new gaming club, Nathaniel played “Among Us,” a game turned wildly popular among teens seeking virtual camaraderie during the pandemic.

In the church basement on Election Day, the muzak cut off, and Nathaniel straightened, stumbling over the voter’s name on his screen.

“I’m calling to remind you to vote — or, um, I guess, see if you already voted,” he said, and cringed.

WINTER: More Fs, fewer students logging on, and a brewing battle with the Chicago Teachers Union

In December, amid a spike in coronavirus cases that had caused infection rates in the city’s majority Latino neighborhoods to soar, Leonel’s assistant principal emailed him. A teacher had flagged her after Leonel said he needed a day off. On a hour-long Google Meet, the assistant principal talked up positive thinking and mindful breathing. Touched by the unexpected offer to help, Leonel opened up about the pressures of that winter.

At first, he had believed the presidential election’s uncertain outcome explained his relentless panic attacks. The stakes had felt high for a gay kid from an immigrant family. But Joe Biden had been declared the winner, and still the panic attacks kept coming.

After one episode, Leonel’s mom gently broached an issue that had hung over them: “I don’t think you are ready to live on your own.”

Leonel, who was scrambling to meet college application deadlines, didn’t push back. His mom was probably right. But part of him clung to the idea of striking out on his own.

That afternoon on Google Meet, he told the assistant principal about allowing himself to cry recently — a release from his upbringing’s expectation that, as a man, he remain stoic. They made a plan: He would get a physical, and then the school would refer him to a therapist.

In the coming weeks, Leonel waited for the school to check in with him, wishing staff would follow up. But he knew that many teens — at Solorio and across the country — were struggling with mental health. His challenges, by comparison, felt insignificant — even as they threatened to derail him.

Early data has made it clear that the pandemic’s academic fallout has been wildly uneven, setting back further students, including Black and Latino youth, who were already vulnerable. Much less is known about the effect on gender disparities.

Girls have faced their own set of hurdles, including handling child care and remote learning for younger siblings. But some educators believe the disruption has hit boys harder, causing them to disengage at higher rates. And some solid evidence is trickling in.

Data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center shows that while college and university enrollment dipped across the board last fall, the drop was seven times larger among men. That decline was especially steep at community colleges, which serve more diverse, first-generation students like Leonel.

In a new data analysis of fall 2020 test scores by the NWEA, Black and Latino boys made significantly less of their typical growth than Black girls and Latinas, who themselves showed less growth than white and Asian peers.

“We know many of these kids were already behind before the pandemic,” said Megan Kuhfeld, a NWEA senior research scientist. “This is compounding already existing inequities.”

And in Chicago, attendance and grading data for the first half of this past school year showed disproportionate impact by both race and gender as well.

The reasons for that uneven fallout are not entirely clear, but advocates and experts say a slew of factors likely are at play. There’s the added pressure young men feel to pitch in to family budgets, and the research suggesting girls are better at staying on task independently, a key skill during remote learning.

Educators such as Vienna, Leonel’s OneGoal mentor, say computer school took away opportunities to peek over students’ shoulders and offer suggestions, or bond informally in hallways. That’s significant because, as research has shown, boys are less likely to reach out to educators for guidance, notes Huerta, the University of Southern California professor. Home and community culture, with a premium placed on male self-sufficiency, play a part. But school norms have fed into this dynamic as well.

“In the classroom, boys are conditioned to sit down, shut up and not be a disruption,” Huerta noted. “Do we really expect them to reach out and ask for help 10 years later?”

At Austin Academy, Derrick’s math teacher, Steven McIlrath, didn’t wait for students to ask for help. On some days that winter, the school’s virtual attendance dipped below 40%. A quarter of McIlrath’s students went missing, and he called some homes as many as 10 times.

McIlrath repeatedly called Derrick’s mom and emailed the teen: Why wasn’t he logging on?

On a cool, blustery February evening, Derrick sat at a long table in an office off the sales floor of an Austin bicycle shop, where Mikala Barrett’s VOYCE group had started meeting in person. In an “Outlaw Cycles” jacket with faux leather peeling under his arms, he slumped in his chair, peering at his cell phone. His shoe stencil business idea had fizzled out months ago.

Later, the half dozen students spoke about a friend who was shot and killed last year, one of two teens lost to gun violence for whom they recently held a candlelight vigil. Barrett paused and looked around the room.

“So, how’s school?” she asked. “For the two of you who are still going?”

Derrick stopped logging on to virtual school last semester, and failed his classes. But he clung to a precarious connection to his school. He never turned off the Google Classroom notifications on his phone, and it pinged each time teachers posted assignments. And he continued to respond to emails from McIlrath, just to say hello.

Anna, 16, Derrick’s stepsister, a sophomore at Englewood STEM High, urged him not to give up. Yes, virtual learning was rough. An A and B student, Anna also struggled with motivation. But did he want to send her and his other younger siblings the message that it’s cool to drop out?

“It’s like when your basketball team is down by so much,” Derrick countered. “There’s no point in watching any more.”

To Derrick, returning to Austin Academy’s classrooms seemed the only way out of his stalemate. But district and teachers’ union officials were caught up in one of the most acrimonious standoffs over reopening elementary schools nationally. There was no plan or target date to reopen high schools — and little discussion of improving teens’ virtual experience.

In the meantime, Derrick put in applications at a couple of big box stores, but had not heard back. He fell back on his mantra: It was the same thing over and over.

At the bike shop meeting, he looked up from his phone.

“School’s going great,” he offered.

Barrett held his gaze until he looked away.

Unlike Derrick, Nathaniel continued to log on to classes daily, but he was increasingly struggling to stay engaged.

One afternoon, Nathaniel unmuted his laptop mic during a virtual drama class and called out to his partner on a project due in a couple of days. Nathaniel sat cross-legged on the floor, wedged between his bed and a dresser, a cup of ramen cooling on the windowsill. His view was a brick wall an arm’s length away, his room immersed in gloom even on a sunny day.

“Hey, real quick,” Nathaniel asked. “Which character did you pick for the costume design?”

But like him, his fellow student had his camera off — and had apparently wandered away from the screen.

His classes these days were nothing like the lively virtual meetings with his VOYCE group. Nathaniel had even gotten to MC a virtual town hall, where students said they wanted the city to invest its school cop dollars into counselors, librarians, and restorative justice coordinators.

After many meetings to prepare for the event, Nathaniel came off as confident and laidback.

But the more he got the hang of student activism, the harder it seemed to keep his mind on school work. He failed two classes during the first semester, and should have signed up for evening credit recovery courses. But that was when VOYCE students met to chart next steps in the district’s “Whole School Safety” initiative.

Next up was a Civil War documentary for history class. But 10 minutes in, Nathaniel’s attention had drifted. He donned headphones in front of a larger screen on his wall and started a video game, which whisked him from the 19th-century battlefield to a stark futuristic landscape.

SPRING: Chicago high schools reopen. But where are the students?

In April, Chicago reopened its high schools, but Leonel opted out of in-person learning. The decision weighed on him: Returning might help him catch up after he and his entire family got sick with COVID, sidelining his studies. But he was too worried about having a panic attack in the building.

By spring, several colleges had accepted Leonel. One admissions counselor, at Arrupe College in Chicago, gave him a call to share the news, sealing the deal. Leonel was drawn to the supportive, small-school feel at the affordable community college within the private Loyola University. Already, Leonel was reaching out to staff there almost every week, forging a bond.

Settling on a college shifted his perspective. After working so hard to achieve this goal, would he really let anxiety keep him away from college classrooms in the fall? Besides, he spent time with his friends for the first time in months and was astounded by the change in his sense of well-being.

“When I am with my friends,” he told his mom, “I forget I have anxiety.”

Leonel decided to go back in person after all. At first, school officials said the deadline had passed. But a couple of weeks later, he got the green light and returned to finish his senior year on campus.

In Chicago, nonprofits that focus on boys and young men of color kicked into gear that spring, questioning how the city can reimagine the way it serves these students. More robust mental health support is top of mind here and nationally.

VOYCE, the group Nathaniel and Derrick work with, has partnered with Lurie Children’s Hospital on a new project called Ujima, in which teen boys of color will weigh in on addressing the mental health needs in their communities.

The school district along with the nonprofit Thrive Chicago and My Brother’s Keeper, one of President Obama’s signature initiatives, are launching a pilot project in the fall to steer more Black and Latino boys to careers in teaching, presenting education as a form of activism, said Sonya Anderson, Thrive’s president.

Maurice Swinney, the Chicago district’s inaugural chief equity officer and now interim education chief, hosted a focus group with Black male students who spoke about the pressure they feel to contribute to family budgets amid the crisis. Swinney says the district is working to cultivate after-school job and internship opportunities that complement students’ long-term goals.

Vienna, the Solorio adviser, says internet school starkly exposed a chronic failure to teach students skills needed to succeed in college, including advocating for themselves, managing their time, and working independently. Next fall and beyond, he says, schools like Solorio should double down on cultivating these skills.

“Many within education want to go back to business as usual,” Vienna said. “I sincerely hope we don’t.”

That spring, Derrick gave school another try. His mom and school officials teamed up to encourage him, promising teachers would help him get caught up. But his comeback didn’t stick.

He had missed the email inviting him to opt into in-person learning. Once Derrick felt that opportunity would change everything. Now it seemed the moment to seize it had vanished.

In early June, Derrick got an unexpected call from a new mentor his school assigned him: She urged him to enroll in summer school and told him he would go to an alternative high school in the fall. He wants to start taking classes to get licensed to sell life insurance — another crack at his entrepreneurial dream he knows will require a high school degree.

Across the district, about a third of high schoolers, including Nathaniel, returned to in-person classes. On a crisp Friday morning in late April, his mother, Miriam, dropped him off at Roosevelt, more than a year since he had last been on campus. By then, almost 5,500 people had died of COVID in Chicago.

At first, Nathaniel couldn’t recognize anyone, and no one seemed to want to talk. Still, both mother and son had high hopes for his return.

A month earlier, a furious Miriam had stormed into Nathaniel’s bedroom, holding his first semester grade report. He teared up — the first time he had cried in front of her.

“I don’t want to disappoint you,” he told her, and she softened.

That first day back, Nathaniel’s photo was on the front page of the Chicago Sun-Times, with a story in which he and other students argued that Toledo’s killing in a Little Village alley strengthened the case for removing cops from campus. That afternoon, the district announced that it would pull officers from its high schools for the remainder of the school year.

Nathaniel had come into his own as an advocate.

But school was another story. Returning to the building two days a week was not a cure-all. He was still trying to relearn the routines of in-person school. Some mornings on his in-person days, he just stayed at home to log on remotely. Roosevelt was working on a plan to help Nathaniel and other students who had remained engaged in learning to get caught up over the summer and into fall.

In early May, Nathaniel again lay awake in the early dawn hours, all his screens dark, sleep still elusive. The coming months loomed: a grueling slog and a thrilling ride rolled into one, make-or-break.

“Nate, you are all over the place,” he admonished himself. “You gotta get back on track.”