A new school year begins in Chicago Monday. There will be familiar rites of passage — new backpacks, teachers, and classmates — and some unfamiliar ones as schools navigate evolving rules amid a pandemic that is constantly changing shape itself. Here’s what to know.

1. Some familiar COVID mitigations will be back — masks, abundant hand sanitizer — but there will be notable differences.

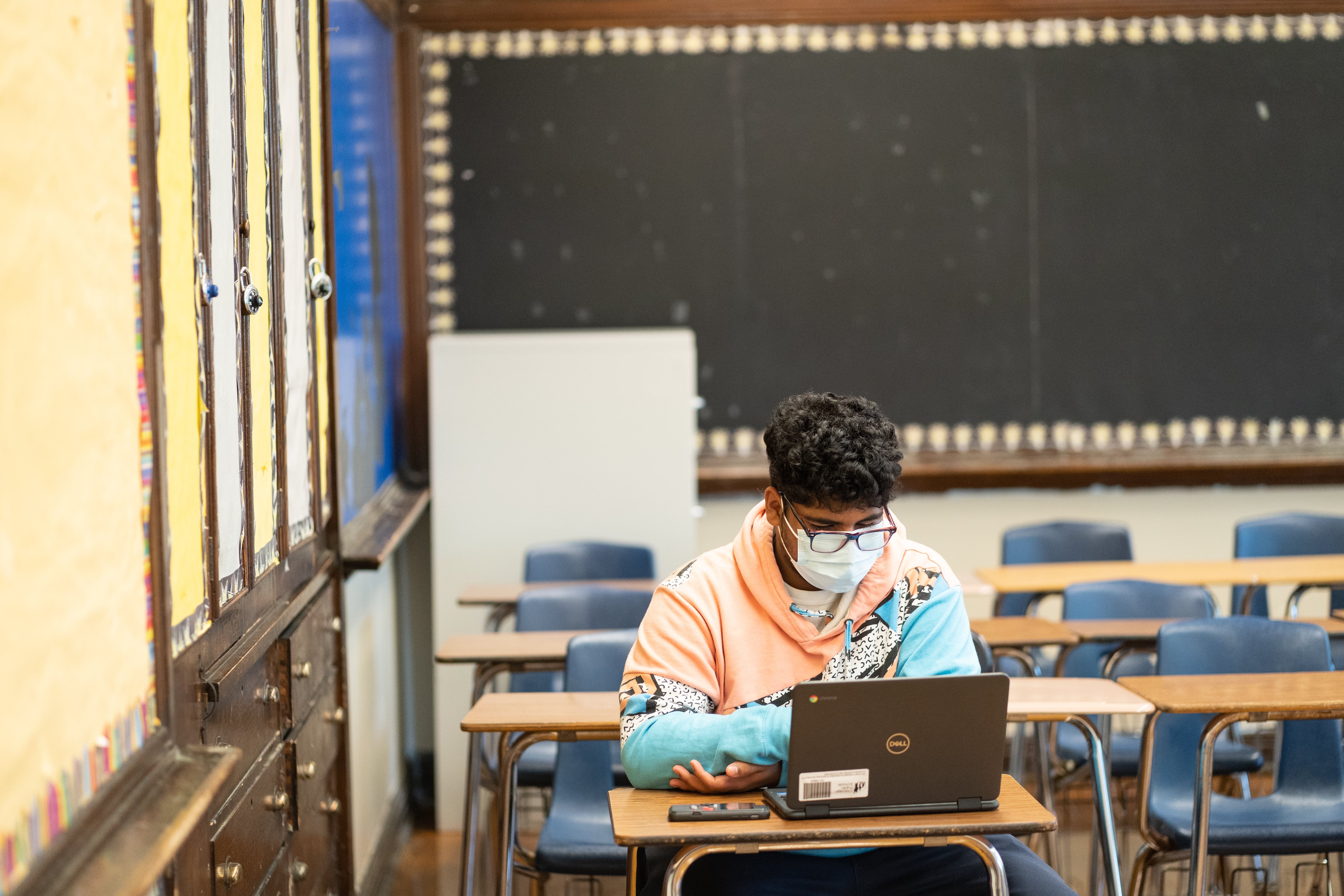

Chicago schools are fully reopening for the first time in 533 days after a scaled-back spring reopening when only a fraction of students returned to campuses.

What will be similar to the spring: mask requirements indoors (students may remove them for outdoor activities, sports, and meals), HEPA air filters in every classroom, and copious hand sanitizer. The district has expanded its contact tracing team to 24 people, so parents and students will continue to be notified if COVID-19 cases are reported on their campus.

Chicago has also broadened its voluntary surveillance testing program for district employees, who can test weekly, and for students — but weekly tests will be offered to students only if community transmission rates are moderate to high. On Friday, as a parent group held an event to question the district’s testing preparedness, officials affirmed they have a vendor lined up to begin offering antigen tests to all students and employees on Week 1.

There will be some changes. Gone is the pod system that limited classes to 15 and the daily electronic screener. Also gone are temperature checks, which officials said weren’t a great COVID-19 indicator.

One of the biggest differences will be social distancing guidelines. In the spring, schools were supposed to keep everyone six feet apart. Now guidance from the federal government and the state encourage three feet distance, but gives schools considerable leeway.

How some of Chicago’s more densely packed schools adjust lunch schedules, recess plans, and work to reduce class sizes will be something to watch — and something for parents to ask about during the first few days of school.

2. District officials have said they are serious about reopening and staying open — but a late rollout of some safety protocols has made some parents and educators nervous.

Chicago’s interim CEO, José Torres, made it clear from his appointment that fully reopening schools was top priority. But detailed guidance on quarantining protocols and other details wasn’t public until this week because Torres said the district did not want to move “too far ahead” of ongoing negotiations with the Chicago Teachers Union.

The union has called on stricter safety measures — and that could continue to be a point of contention even after the school year starts. At a school board meeting Wednesday, union President Jesse Sharkey told board members the union has no intention of blocking the start of the school year. But he said the CTU will continue to “ring alarms” about what he described as safety shortfalls, and in a Friday bargaining update, accused the district of “making the cheapest attempts at safety,” despite billions in federal emergency dollars for COVID-19 response.

The union wants a more stringent approach to quarantining students and employees and thresholds for closing school buildings. And it has asked the district to explore more creative ways to maintain three feet of social distancing on campuses, including moving more meals and other activities outside.

Torres struck an optimistic note, saying the district is “very close” to striking an agreement with the union. He also expressed commitment to improving a “broken” relationship with the CTU.

3. Despite calls for a broader remote option for more families, that’s unlikely — for now.

Families and the city’s teachers union have called for a more widespread virtual option, but state guidelines currently limit what districts can offer remotely.

Chicago established a “Virtual Academy” for children with serious health conditions, and while it has said 4,260 students qualified according to its records, only 750 applied — even after a deadline extension.

Of them, about 370 students were accepted into the academy, whose mascot is the Virtual Viper, with several dozen applications still under review. At this point, the district is only accepting applications from students who just recently moved to the district or received a new medical diagnosis.

Some families have argued the criteria for the academy were too stringent. While some conditions automatically qualify families for the academy, others that put children at a higher risk from COVID, such as asthma, only make students eligible if their attendance last year was spotty. That, some parents say, penalizes those who worked to ensure children logged on regularly. Others were likely turned off by the fact that healthy siblings cannot attend the Virtual Academy.

4. Teacher vaccinations are now required — but vaccinating eligible students has proved a challenge.

In August, Chicago joined a list of other big city districts that said teachers must be vaccinated by Oct. 15 to continue to work. (Illinois followed with a statewide mandate this week.)

But student vaccinations have proved a trickier topic. Children under 12 still don’t have access to a vaccine. Citywide, among children ages 12-17 across public and private schools, 57% had received one dose of the vaccine and about 45% were fully inoculated as of Aug. 24, with wide variation among neighborhoods.

Tracking who is vaccinated and who isn’t could also prove challenging: In Chicago schools, only student athletes are required to show proof of vaccination or undergo weekly testing, not the general population.

District officials have acknowledged the key role schools play in the vaccine push and set up eight school-based clinics but expressed disappointment with tepid demand. To date, it’s been mostly district employees taking advantage. Only about 1,400 doses were given to eligible students and their family members at the school clinics and more than 300 inoculation events over the summer.

“Our capacity to administer vaccines profoundly exceeds demand among families with children 12 and up,” said Dr. Kenneth Fox, the district’s chief health officer, who at the Wednesday school board meeting made an impassioned plea for families to get the vaccine.

5. There are big concerns about how many students will show up and how to find those who don’t.

District officials this week said they pulled out all the stops to connect over the summer with the families of students who disengaged or only intermittently participated in learning last year. That included home visits by both district employees and staff at partner community groups to about 18,000 students flagged as being at a high risk for not returning this fall.

The district was able to engage with the parents or guardians of about 75% of them. For those 18,000 students, the district also plans one-on-one mentoring and more home visits in the coming weeks if they do not show up to school next week.

Nevertheless, said Erin Galfer, deputy chief of the Office of College and Career Success, “We anticipate there are some students who will not come back because of concerns over COVID-19.” She said the families of these students will be the focus of intensive outreach in the first weeks of the school year.

At a Friday press conference, Mayor Lori Lightfoot said the district’s “full court press” to track down disengaged students will continue: “That work doesn’t stop on Aug. 30. We’ve got to reach out to young people and bring them back.”

6. Schools will have more money — and face steeper challenges.

Many educators have said that their most important job this school year will be making sure the students are alright.

Students and educators alike have testified to the deep trauma caused by the pandemic and the rise of gun violence in Chicago. The district, which will gain nearly $3 billion across three federal emergency spending stimulus packages, has said it is investing considerably in mental health and academic recovery through a “Moving Forward Together” initiative that will cost $525 million across two years and make more money available for schools. A sliver of that will be spent on additional counselors — $5 million — but a considerable $75 million chunk will be outsourced to 69 vendors to provide social and emotional support services.

Advocates are beginning to push for answers about how the district will ensure students get the services they need — and what data will be tracked to see what’s working and what isn’t.

How schools will gauge the pandemic’s academic impact — and how much of that data will be shared publicly with parents and policymakers — will be a key storyline moving forward. Evidence of the pandemic’s impact on school children is still emerging, and the data is scattered. On average, first through sixth graders fell five months behind in math and fourth months behind in reading, according to national researchers. Black, Latino, and low-income students were hit hardest.

In Chicago, data is so far limited, but attendance figures from last spring showed higher-than-average rates of absenteeism, particularly among the city’s most vulnerable students and early learners. When it came to grades, Chicago students logged more As, but also more Fs. In high schools, Black and Latino boys saw the highest increase in the share of Fs.

Despite all of the pandemic’s uncertainties, Chicago is pushing ahead with the rollout of its $135 million curriculum project called “Skyline,” which officials say will establish a centralized set of lessons that are more culturally relevant and adaptable across schools. That change will herald a new suite of assessments — Chicago officials are dropping the NWEA MAP test they have used widely since 2013 and bringing in a spate of new tests — yet another example of how school will look considerably different from the pre-pandemic era.